hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

“A bundle of blackened bones”: The search for unmarked graves of those killed in Gwangju Uprising

“I can’t tell you how shocked we were to find a bundle of blackened bones tied with a nylon cord in the grave we were digging up in the black of night,” said Yang Gi-nam, who said he will never forget what happened on that early fall evening in September 1988.

The 62-year-old man, formerly named Yang Dong-nam, spoke with the Hankyoreh on Friday in the Chipyeong neighborhood of western Gwangju’s Seo District. The interview took place at the office of an organization for veterans of the “mobility strike force” that was organized by Gwangju residents during the uprising in May 1980.

While the National Assembly was hard at work preparing for hearings to investigate the bloody massacre of Gwangju citizens and corruption by government officials, Yang and a few other former members of the city’s mobility strike force were passing along tips about secret burial sites to the office of Jeong Sang-yong, who was a lawmaker with the Peace Democratic Party at the time.

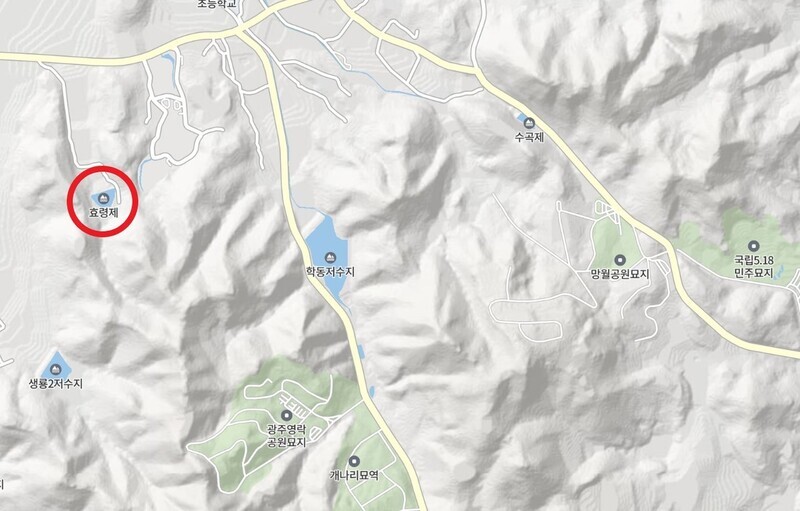

“In order to avoid snooping cops and soldiers, we ran our tip-soliciting office out of a room at a motel in Gwangju’s Yang neighborhood. One day, a resident of the Hyoryeong neighborhood of Gwangju’s Buk District reported seeing a garbage truck moving several sacks to a cemetery while working in a rice paddy near Hyoryeong Reservoir in May 1980,” Yang recalled.

When Yang and his colleagues visited the cemetery in the early morning hours, they discovered a row of four or five mounds about 50 centimeters high and 1 meter long on the edge of the cemetery. Other than farmers, hardly anyone visited the site, which was about 2 kilometers from the cemetery in the Mangwol neighborhood.

In the dim glow of their lanterns, the group excavated one of the mounds and found a bundle of bones about 50 centimeters long, tied up with pink nylon. Rather than the yellowish color that Yang had seen on other bones, these were black, as if they’d been scorched. Given the number of bones, Yang figured he was looking at least one person’s remains.

“We were in such a hurry back then that we would dig up what we suspected were secret burial sites in the middle of the night without getting permission from the authorities. Since the bones were blackened and tied up with a nylon cord, we figured we’d finally found one,” Yang said.

Yang passed the remains along to Jeong’s office, but the provincial office wrote them off as belonging to a vagrant.

But Yang had his doubts. When the corpse of someone with no connections was cremated in 1980, the standard procedure was to bury the remains in the city cemetery in the Mangwol neighborhood, in Buk District. But Yang couldn’t exactly dispute the officials’ account given the shady nature of digging up graves.

It was in 2019 that Yang was reminded of those bones. That was after he heard testimony from Heo Jang-hwan, a former investigator with the Gwangju 505 defense security unit, that the bodies of citizens had been incinerated with bunker C fuel oil in the boiler room at the military hospital in Gwangju during the uprising.

Some experts on the uprising have said that Heo’s testimony isn’t credible, but Yang disagrees. He still remembered what he’d heard from a medic named Choi while he was in the military hospital on Aug. 13, after being tortured during interrogation following his arrest at the South Jeolla Provincial Office on May 27, 1980.

“This is what Choi said: corpses come into the hospital, but none go out. While surveying the area around the hospital in 1986, residents told me that the military hospital’s boiler room had been running nonstop during the uprising and had belched out so much soot that they didn’t dare open their earthenware jars [for fermented foods],” Yang said.

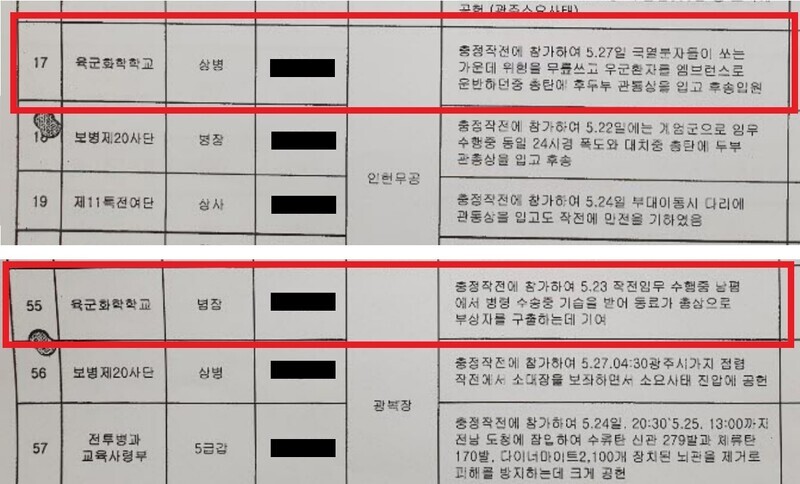

“I heard the boiler room at the military hospital was turned into an ad hoc crematorium that was run by two members of the chemical unit. They even received a medal for that,” said Kim Jong-bae, 67, who was chair of the student committee during the uprising and later served as a member of the National Assembly.

The awards that the Martial Law Command gave out for the Chungjeong operation on June 20, 1980, include an Inheon Order of Military Merit for a corporal and a Gwangbok Medal for a sergeant, both from the military’s chemical school.

Yang believes that what he heard from Choi and people living near the hospital, the blackened remains he saw in 1988, and Heo’s claim are all connected.

By Kim Yong-hee, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 2Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 3Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 4[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 5Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 6Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 7[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 8[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 9New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 10Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76