hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

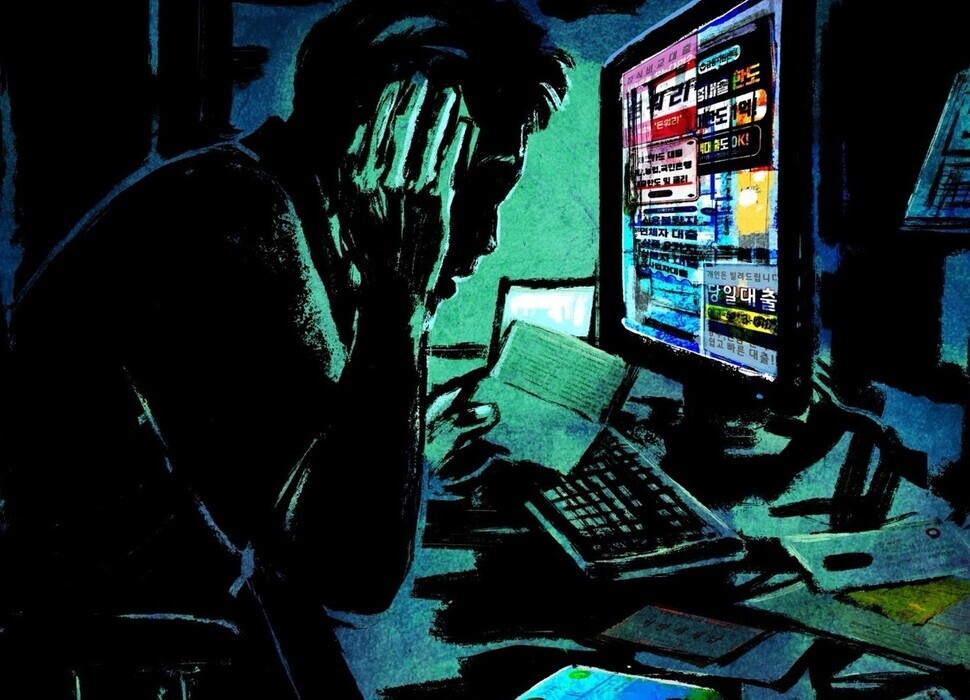

Mortgaged futures: How debt, default are coming to define lives of young Koreans

Debt has been rising at a steep rate among South Korean young adults amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Observers hold different views of the situation, with some attributing it to “moral hazard” and the trend of incurring debt in order to invest, while others see it as a “generational tragedy” for young people facing unstable prospects in both assets and employment.

But certain facts remain undeniable: At 11.3%, the proportion of South Koreans in their 20s and 30s whose debt has reached critical levels is nearly twice as high as the 6.3% average for the generation that came before them — and experience shows that the uncertainties of today have damaging consequences for tomorrow.

To get to the bottom of any issue that elicits a divided response, we must first establish an accurate picture of the situation. The same is true for the debt shouldered by South Korea’s younger adults.

In order to get a closer look at the lives of young people who have mortgaged their futures, a Hankyoreh reporter worked for three weeks at a lending business, which is classified as a “third-tier financial institution.” In-depth interviews were also carried out with 16 young people who have gone into debt for different reasons.

To understand more about the effects that debts can have over a lifetime, we heard from older adults who have suffered for decades due to debts incurred in their 20s and 30s. The results are presented in the Hankyoreh’s series “Mortgaged Futures: Young Koreans in Debt,” an analysis of the issue of young South Koreans’ struggles with debt.

Hounded by collectors

“I’m not dodging calls on purpose. My phone was cut off because I couldn’t pay the bill. [. . .] Once I get my paycheck, I’ll have it turned back on and get in touch with you right away.”

“A” is a 34-year-old with a strikingly meek voice in which they stammer “I’m sorry,” over and over. They are also a longtime user of lending businesses.

The debt that has A so cowed at the moment is a mere 1 million won (around US$720) — which they borrowed eight years ago, in 2014. At the time, A was 26.

Over the past eight years, the interest has amounted to 2.25 million won, or more than double the principal. During the same time, A has paid back just 30,000 won out of the original loan.

They had been diligent about making payments, but began falling behind more and more frequently in the first half of 2018. That coincided with a period of increasing gaps in their employment history.

Already struggling with a precarious working situation, A struggled to find work when the COVID-19 pandemic hit.

“I’ll give you my roommate’s number. Call there if you can’t reach me.”

A’s urgent request came after they had started receiving collection calls at a job they had finally managed to land. They had been unable to come up with their monthly interest payment of just over 16,000 won, and the collectors had sidestepped the disconnection of their cell phone service by contacting them at work. A’s head slumped when they realized who was on the other end of the line.

Lenders are financial institutions of last resort for people who have no assets or credit, or who have too many existing loans to take out money from other institutions. The only options after them are private loans, daily installment loans and illegal lenders.

This explains why so few people ever start going into debt with lenders. While I did not find out about A’s other liabilities, it appears likely that the reason for their problems paying even a small amount of monthly interest stems from other borrowings. This was typically the case for people in debt who turned to lenders.

In July, I went undercover working for three weeks as a counselor at a lending business in Seoul. My job was in collections: I was tasked with calling around 300 people a day and demanding payment of their interest or principal.

The calls were made on or just before their contracted interest/principal repayment date, or after they had fallen behind in their payments. Around 150 of the borrowers — roughly half — were people in their 20s and 30s.

The list of names changed from day to day, but the age distribution did not. Just over 10% of the borrowers answered the phone; that rate was even lower among the younger people.

This was how I came to speak over the phone with around 100 people in their 20s and 30s who were struggling with debt. Their stories were all different, in terms of the amount they had borrowed, how long they had been repaying it, and how many times they had been delinquent. But all of them shared the same limp, defeated tone of voice.

Young people classified “defaulters” over 5 million wonAnother commonality was the situation that A faced: struggling for many years to pay back what had been a relatively small loan.

These borrowers do not have much in the way of credit or collateral in the first place, so they don’t have the option of borrowing very much. Even if they managed to get a loan approved, they would be unable to pay off the principal, as they struggle to pay lender interest rates that reach as high as 20%.

When the young borrowers were told that their loan payment had come due, not one of them said they intended to pay back the principal. Instead, they asked, “Can you extend the due date so I can just pay off the interest this month?”

For them, maintaining their level of debt seemed to be the best option. Extending the due date was easy: All they needed was an online contract, after confirming that their workplace and home address hadn’t changed.

When the borrowers didn’t answer, their due date was automatically extended. That’s how simple it was to perpetuate their status as debtors — a status with no expiration date.

For young people with no assets and uncertain employment prospects, even a loan of a few million won can be a trap that is difficult to escape from.

When borrowers are unable to repay their loans — such as being delinquent on paying back an amount of 500,000 won for three or more months — they are registered as a “defaulter.” According to data from the office of Democratic Party lawmaker Jin Sun-mee and the Korea Credit Information Services, 41% of people in their 20s who had defaulted on financial liabilities were facing disadvantages in various financial transactions due to loans of 5 million won or less (US$4,600). For people in their 30s, the percentage was 29.4%.

Across all age groups (25.5% average), young people represented the largest proportion of people classified as defaulters due to loans of 5 million won or less. This means that many young debtors are unable to even keep up with small interest payments on small loans.

Another reason people are unable to repay even small loans a decade later is that they have multiple loans.

“B,” a day laborer in their early 30s, borrowed 5 million won in 2012. Ten years later, they have paid over 10 million won in interest — and zero toward the principal. When B’s other loans are factored in, they face a total principal balance of over 200 million won.

B had been delinquent numerous times and did not answer the phone that day. Over 90% of the young people I called during those three weeks were people like B who had multiple outstanding loans.

When borrowers get caught in the vicious cycle of multiple loans, escape is virtually impossible.

“C” had four different outstanding loans in 2016, when they were in their early 30s. Six years later, that number has increased to 28. Young people continue seeking additional loans even as their debt mounts.

“D” was in their early 20s when they came calling to a lender with 25 million won in outstanding loans. Within three years, they had shouldered 55 million won in debt.

The lending company ended up refusing 11 additional loan requests from D, concluding that they did not have the means to repay them. Given that borrowers cannot reapply until two months have passed after the previous loan request was rejected, this meant D had been returning to the business for additional loans for over two years.

A random sampling of 30 people in their 20s and 30s whom I called about their loan deadline showed that they were earning 1.5 million to 2 million won a month on average and using 52% of that to pay off debt. The average borrower also had around ten different liabilities.

With so much spent on repayments, they were having difficulty surviving on what was left over. Some young people were forced to spend 80% to 100% of their salary on interest payments alone.

These were people who were literally turning to lenders as a last resort, facing debt burdens that already ranged from the tens of millions to over 100 million won.

“At this point, they can’t even rob Peter to pay Paul anymore. The debt is impossible to escape,” explained an employee who looked over the liabilities with me. “It’s not like these are people with good jobs.”

The severity of the multiple loan problem among young people is also borne out by statistics.

According to figures from the Financial Supervisory Service and Democratic Party lawmaker Lee Jong-mun, the rate of increase in multiple loans (borrowing from three or more financial institutions, including lenders) was 22.1% across all groups for the roughly four-year period from December 2017 to April 2022. Among people aged 39 and under, the rate of increase was 32.9%. The total principal for young people with multiple loans rose by over 39 trillion won during that time.

Why collectors have to be toughEmployees at lending businesses have to learn to be tough on borrowers. The reason comes down to competition: There are many different financial institutions and lending businesses chasing after interest payments from a given borrower with multiple loans.

The business that I worked for began calling borrowers about their upcoming deadlines around two days ahead of time. On my first day on the job, I used a gentle, apologetic tone when making a collection call for a payment that was not yet delinquent. The team leader immediately called me over.

“You’re being too quiet. You can’t let them look down on you. People who are in debt to multiple places may decide which creditor to pay based on their attitude.”

When I complained to one of my team members about the scolding, they took my manager’s side.

“More forceful employees do tend to have a better record. Debtors seem to conclude it’s better to pay up than to keep getting that kind of phone call,” my coworker said.

Korea’s Act on Registration of Credit Business and Protection of Finance Users is much stricter about debt collection than it used to be. Lenders can be prosecuted for causing debtors fear or anxiety or disturbing their work or private life.

Shouting and verbal abuse are strictly prohibited by company regulations. As such, collection employees need to learn how to twist debtors’ arms without crossing the line into illegality. Diligent nagging is needed to ensure you’re the first person debtors think of when they come into some money.

After another collection team got reprimanded for poor performance, they raised their voices on calls throughout the day.

“So when are you saying you can pay us this month? I don’t think we can wait that long.”

“Why on earth are you so late every time? We’re busy people, and you keep coming to us with excuses. You never have a decent explanation, either.”

The tension created by this chilly tone is depressing not only for the debtors but also for the collection staff.

“I’m sorry. I’m sorry.”The way people responded to collection calls varied with their generation. Some of the middle-aged debtors were considered problem customers because of their “make my day” attitude.

But young people either refused to take calls or answered in a demoralized tone.

“I’m crashing at a friend’s place because I can’t afford to rent my own. My salary isn’t enough to cover the interest, so I’ve started a part-time job at night. Can you wait a little longer?”

“I was charged twice for the TV fee of 2,500 won, so I don’t have any money in my account to pay interest.”

Such statements were followed by a silence that was charged with a mixture of contrition and embarrassment.

Young people can do little more than say they’re sorry given the difficulty of breaking out of the cycle of debt. When they finally pick up the phone, after letting it tediously ring over and over, they frankly apologize.

“I’m so sorry. I’ll pay right away. I’m sorry.”

“My monthly salary hasn’t come in yet. What am I supposed to do? Can you give me until tomorrow?”

Their desperate appeals often left me at a loss for words.

The same young person who had griped about a call reminding him about an upcoming interest payment was quick to apologize on the phone not even a day after he missed a payment.

Even when the amounts they owe are relatively small, these debtors feel obliged to apologize fervently to debt collectors they’ve never even seen. And when they go several days without making the due payment, the collection work is handed over to another team.

When I hung up a call, feeling gloomy about dealing with so many sullen voices, I would recall what a boss told me during training.

“There will probably be a lot of customers who get angry and curse at you. Don’t let their reactions get to you. It’s better to assume they’re not mad at you, but at their lives and the situations they’re in.”

But the most common thing I heard while calling young people about their debts wasn’t shouting, but quiet sighs. It was unclear whether the sighs were directed at my persistent phone calls or at themselves for once again failing to make their payments on time.

Their sighs were aimless, with no expectation they would be heard. Young people who are trapped in debt aren’t angry, they’re simply exhausted.

About the reporting process

Following a legal review, the Hankyoreh reporter gained employment at a lending company and worked in debt collection there for two weeks, following one week of training. The reporter chose to work in the field with the goal of analyzing the issue of youth debt from another angle. The reporter thought that examining the situation of youth debtors in the loan market would provide a different understanding of systemic issues than interviewing those people directly.

All wages paid by the lending company are being donated to organizations that help young people deal with their debt.

By Kim Ji-eun, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 3Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 6[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 7N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 10Kim Jong-un expressed ‘satisfaction’ with nuclear counterstrike drill directed at South