hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Blood, puss and pitiful pay: Why Korean factory workers are calling it quits

Vocational school graduate. Holder of various licenses. Very passionate about work. Choi Ye-rin, born in 2002, and Kim Su-hyeok (a pseudonym), born in 2001, both entered their first workplaces in 2021.

Su-hyeok got a job at Hyundai-Kia’s tier 4 vendor, while Ye-rin started working at a factory that plates printed circuit boards (PCBs) for smartphones.

The backgrounds of these two in terms of educational background, age, work industry, and occupation are similar to that of production worker Yoon Jeong-min, who was born in the mid-20th century baby boom generation that championed labor unions in the late 1980s, was the subject of Korea’s early social security system, and dreamed of becoming middle class.

The Korean manufacturing industry also still accounts for 255 to 30% of Korea’s GDP. Su-hyeok and Ye-rin were born when the country’s population decline began in earnest, with only 400,000 children being born each year.

The only thing that has changed, the only thing that is odd, is the circumstances surrounding the times.

“Basic labor rights? That’s all a sham,” Ye-rin commented. The two briefly stayed in a corner of the efficient production structure of the manufacturing industry that has been leading the Korean economy, only to soon flee.

Ever since he was a kid, Su-hyeok has always liked machinery. “I dreamt about becoming a scientist, but when I tried to be realistic, I thought it’d be better for me to learn a skill.” Su-hyeok decided to go to a vocational school when he learned it could fast-track him to employment at an early age, and because it would be easier to get into college.

Nine of his classmates shared the same sentiment, which was around one-third of all the students in his class.

Of course, he chose to study machinery. Cutting and molding steel was fun. In the second semester of his senior year, there were around 30 machines in his first job, where he started as a field trainee. Automatic lathes and milling machines used to cut through steel. Never had it occurred to him that the machines that he loved so much would pose trouble.

The machines required a lot of attention. One constantly spewed up oily debris, also known as “chips.” In order to cool the device down to make sure that it turned smoothly, one had to make sure that there was enough cutting oil as often as possible.

Su-hyeok’s job was this: to feed the machine oil non-stop, and to make sure that the “chip tray” was emptied into a gunny sack. He was essentially the machine’s caretaker. Put differently, he was its assistant.

As of 2021, the density of industrial robots in South Korea was overwhelming, even compared to other countries. There are 1,000 units per 100,000 workers. South Korea’s unique mechanization and automation, an advantageous system that makes general-purpose products rapidly, but alienates the autonomy of many workers, is now widespread in small subcontracting factories.

Production workers such as Su-hyeok do not have significant roles among machines. Jeong Jun-ho, a professor at Kangwon National University, explained that “whether it is at a large company or a subcontractor, laborers become replaceable as they only do low-skilled repetitive labor where they only follow the manual or manage machinery. But it isn’t as if the labor itself has become less intensive.”

Since it costs a lot to invest in the machines, they have to keep running, and someone has to stand by and operate them. That was the role given to Su-hyeok.

The true managers of the factories changed. While assisting the untiring metal-cutting machines, Su-hyeok’s hands and feet became embedded with shrapnel. His biggest headache was brass debris. It pierced through his gloves and dug into his socks, and eventually got stuck in his fingers and the soles of his feet.

“Brass chips don’t come out in long strips but break easily into jagged fragments. They’re so small that you can feel the sting when they get stuck, but you can’t really see them.”

He was desperate for gloves. “The white gloves they gave to us workers each day would rip easily when they got cutting oil on them. I asked for more gloves in the beginning, but gave up after no one gave me additional ones.”

He would finish a hard day of work by pulling out the brass chips that were stuck in his fingers and the soles of his feet with nail clippers or tweezers. The field manager told him that in order to not lose money (sales) in this job, production workers have to come to the factory early in the morning and leave work late at night to inspect the machines and run them. The manager encouraged Su-hyeok to look into other technician positions or office jobs. A worker in his 50s knew well what was really going on behind the scenes of factories run by machines.

It is hard for Su-hyeok and his friends to find meaning in labor when their only duty is to stand next to a machine and engage in repetitive tasks. In a survey by Manito, a group formed by vocational school graduates, 68% of vocational school graduates (67 out of 98) from the Ansan and Siheung areas who had found employment in industrial complexes in the past three years (2020-2022), said that they wanted to quit their jobs.

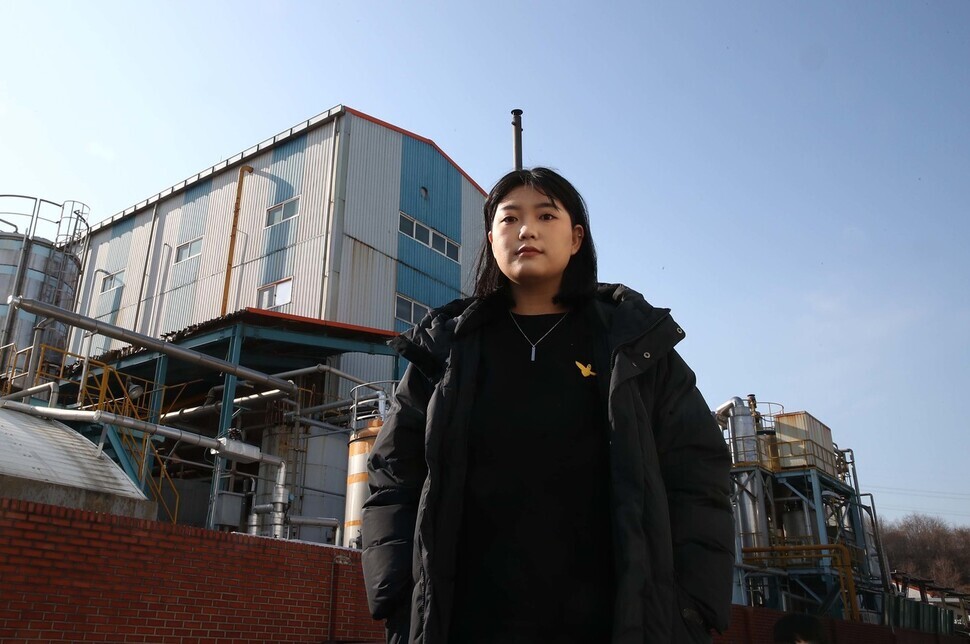

When Ye-rin first entered the plating factory as an on-site trainee, she immediately trusted the place because of the smell. Contrary to preconceived notions that plating factories are dirty and smelly, the factory looked very clean and tidy. Having obtained a license as a hazardous substance engineer and as an environmental craftsman, she was hired as a hazardous chemical safety manager.

Although Ye-rin was an office worker, her manager in charge told her that she had to be in the field to learn the basics of the trade. Little did she know that this meant she would have to soak her bare hands in a plating solution without knowing what chemicals were in it. No one had informed her that this was part of the job.

She saw that the 20 other workers, who were mainly foreigners or middle-aged field workers, had gloves on, so she asked her manager for gloves. The manager ignored her.

Around the plating tank (the container that holds plating solution) were containers that contained strong chemicals such as sulfuric and nitric acid. After she started work by dipping her bare hands into the solution, pus started oozing out of her hands and the skin started to peel off.

“There were many times when my fingernails literally melted, got pierced, and bled. When the acid splattered, the stray acid drops would melt holes in my fingernail, which would then bleed,” she said.

Ye-rin received wages of 1.6 million won (US$1,300) a month.

Even the neat exterior was a farce. “That day they only used gold plating, which smells less, so people were wondering if there would be an environmental inspection. It was only after I was hired that the other workers realized that the managers had done that to make sure that a new hire wouldn’t back out. If the place looked bad, no one would’ve wanted to work there.”

Ye-rin was a worker so necessary to the factory that they had to stop work and spruce up the place.

More and more young people are becoming reluctant to work in manufacturing, a trend that was particularly noticeable last year. As of the first half of 2022, the number of jobs without workers to fill them in the manufacturing industry had increased by 46,000 from the previous year to 176,000.

Most of the businesses in all industries that failed to hire the number of employees they needed (94.7%) were ones with fewer than 300 employees.

Most of the workers that these businesses need are for jobs that only require work proficiency at the level of high school graduates or junior college graduates.

Factories know why young people do not want to work for them. The most common response to the question of why there weren’t enough people in the workforce was “because working conditions, such as wage levels, do not meet the job seeker’s expectations (29.1%), followed by “because these jobs are ones shunned by job seekers” (17.9%). (Ministry of Employment and Labor’s labor force survey in the first half of 2022.)

Su-hyeok also thought that he was a victim of an employment scam when he was hired by a company that needed more workers. During his interview, his manager said that the company could exempt him from his mandatory military service, and would even allow him to keep the job while attending university. However, once Su-hyeok started work, the manager ignored Su-hyeok’s questions and requests for starting the process of military service exemption.

Since most young people tend to leave jobs at the end of the military service exemption period, companies want to delay the start of that period as much as possible.

“Most young people wouldn’t work at a factory that didn’t have that policy,” Su-hyeok said.

Su-hyeok received wages of 1.7 million won (US$1,400) a month. He often worked overtime until 10 pm. Overtime work was concentrated the day before the contractor came for screenings.

“If we heard that the SQ [Hyundai Kia Motors partner quality certification system] evaluation was happening, that meant we’d be working overtime.” As the youngest employee of the tier 4 vendor, a company that cannot function properly without managing a good relationship with its contractor, Su-hyeok was at the very bottom of the huge labor supply chain.

There wasn't much Ye-rin could do to get gloves or Su-hyeok could do about the promise to be exempted from military service. There was no organization standing up for the rights of laborers or for safety at the factories where Ye-rin and Su-hyeok worked.

As of 2020, the rate for unionization at Korean businesses with less than 30 employees was only 0.2%.

“Unions are necessary because I feel like crying out by myself is useless,” Ye-rin said, though she never saw a union form at her workplace.

Meanwhile, Su-hyeok said of union business: “I’m already busy enough trying to make a living.”

Still, in their own way, they showed resistance for the sake of others. Ye-rin and her friends evaluated the company they worked at and gave their reviews to their teachers.

Since factories are constantly reaching out to schools for extra manpower, it was necessary to make a blacklist at least for the sake of the younger students who still had to find a work placement. Ye-rin told her teacher to never send anyone else to this factory, explaining what she had gone through.

Each of the youngsters facing the reality of working at factories had things to say about the experience.

“They gave me a job that is different from my major.” "I am being discriminated against.” “They disregard me because I received an exemption to military service.” The school only became aware of the situation after receiving evaluation reports from those who had already graduated.

“I heard that after I stopped working there, my school stopped sending students to that company,” Ye-rin said, feeling relieved.

The most active form of resistance is to leave such factories. When Ye-rin expressed her intention to leave the factory she was working at, the reaction from her boss shifted between verbal abuse and pleading with her.

“Don’t bother coming in. I won’t give you severance pay,” her boss told her, while peppering in abuse such as, “Does your brain not work because you only went to technical high school?”

But then, on other days, he would completely change his tone, saying things like “where else would I find a talent like you?,” and “shouldn’t we finish the work we started together?”

But Ye-rin did not waver in her decision. “If you hire people with experience, then it will be easier to get work done, but [company management] becomes more difficult. Young people can be paid less,” she said.

Su-hyeok is now working his second job after receiving a definite answer that he would be given an exemption from military service the moment he started working there. He says the welding that he’s learning at the new company is "fun” and something he would like to keep doing. However, he has no plans of staying here in Korea.

“It’s physically demanding and the treatment isn't good either and when I say I work at a factory, people’s perception isn't good. That's why I want to go overseas. Maybe Australia, Canada, or New Zealand? I haven't yet thought about it that much, though,” Su-hyeok said.

Ye-rin and Su-hyeok, children of an era where population decline is such a major problem, each made plans to leave both their factories and Korea.

Young people, who are precious and should be treated as such, are being neglected and treated poorly, their pleading doing little in the face of this contradiction.

By Jang Pill-su, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 4Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 5[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 6Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 7[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 8Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 9Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 10[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady