hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

The valley of 7,000 deaths: Still seeking truth of gruesome Korean War massacres 73 years on

On July 4, 1950, Im Sun-jae walked out of his house, leaving behind a crying daughter who was just over 100 days old. He could not imagine what problems would lie in store if he defied the message ordering him to report to the Yuseong Police Station.

He did not have a good feeling about it. Telling his wife that he would “head to work after stopping at the police station,” he got on his bicycle like any other day.

Born in the village of Eumnae in Hoedeok, a town in Daedeok County (now Daedeok District in Daejeon), Im was bright as a child, and his family had high hopes for him. Since the eldest son’s family had no children, he was adopted by them, but his aunt and uncle treated him as if he were their own.

After graduating from the railroad school during the Japanese occupation, he was hired by the railway bureau in 1944 and began a comfortable working life. He had been named a deputy department director in April 1950 when the Korean War broke out.

After getting on his bike and heading to work like any other day, Im was never seen again.

His family searched everywhere for him. His sister-in-law’s brother, a police officer, visited the Yuseong Police Station to ask about his whereabouts. The fellow police at the station sternly told him not to ask any more questions or do any more searching.

“Apparently he was taken to Sannae.”

It was only after some time had passed that the word “Sannae” was mentioned in connection with Im’s whereabouts.

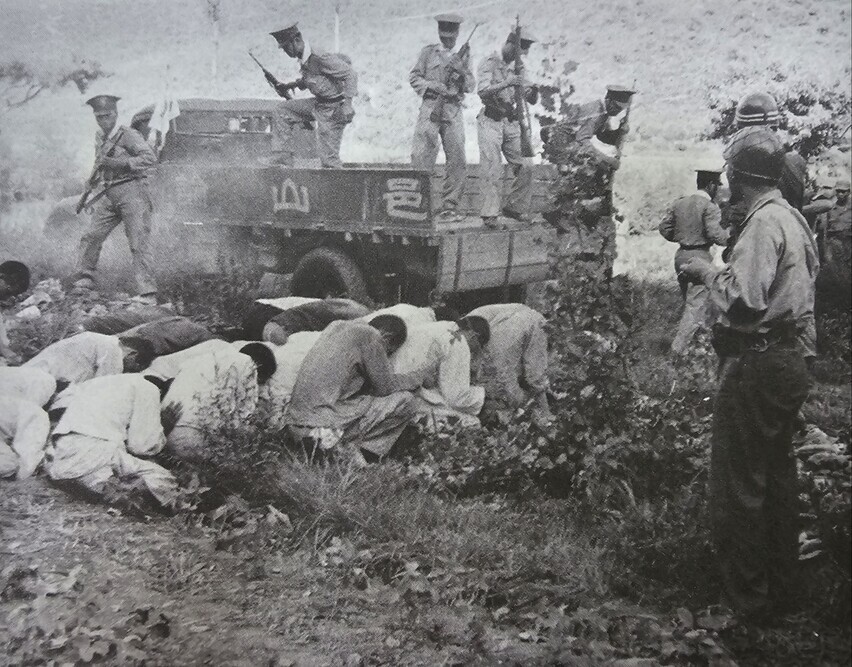

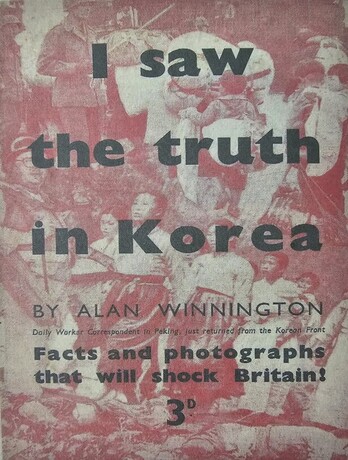

In July 1950, Alan Winnington, a correspondent with Britain’s Daily Worker newspaper, visited the valley of Gollyeong in Sannae, a community in Daejeon.

The following August, he published an article titled “I saw the truth in Korea,” in which he described the scene he had witnessed in the valley.

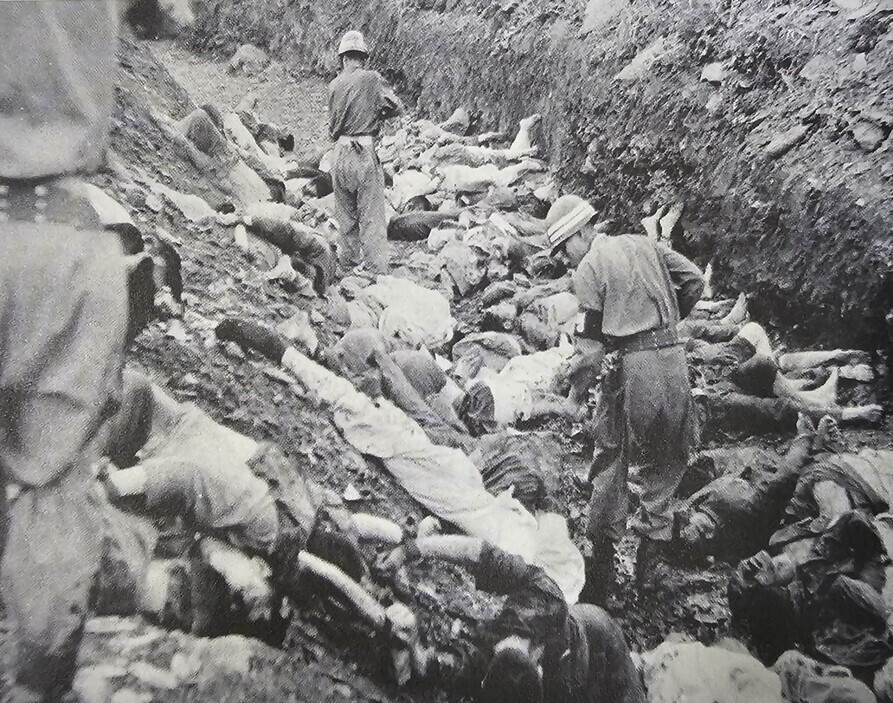

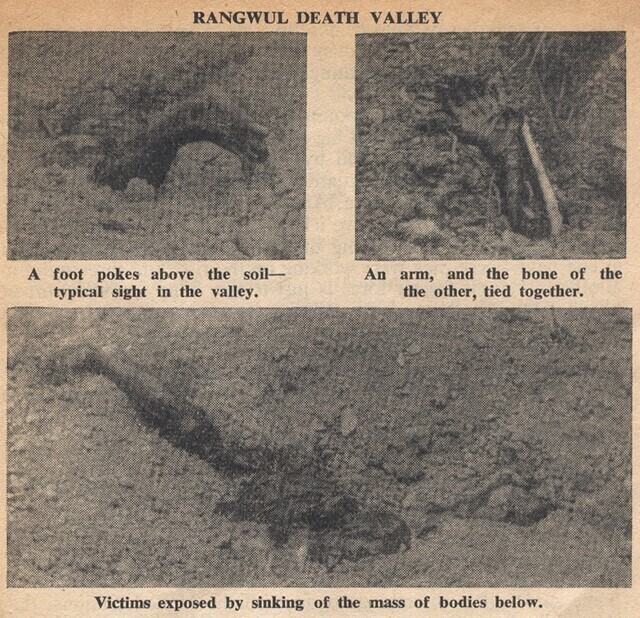

“Every few feet there is a fissure in the topsoil through which you can see into a gradually sinking mass of flesh and bone,” he wrote.

“All along the great death pits, waxy dead hands and feet. [K]nees, elbows, twisted faces and heads burst open by bullets, stick through the soil.”

Winnington arrived at the site just following the third wave of the massacre in Gollyeong Valley, referred to as “Rangwul Death Valley” in his report, which took place between July 6 and the early morning of July 17, 1950. It’s estimated that Im was taken to the valley at around this time.

“On this day, thirty-seven truckloads of at least 100 each were killed—over 3,700, including numerous women,” Winnington wrote in his article.

While it was Korean police who pulled the triggers and slit the throats of these people, wrote Winnington, these were American crimes.

“American officers, with officers of the puppet army, went in jeeps on each day and supervised the butchery,” he wrote in his account.

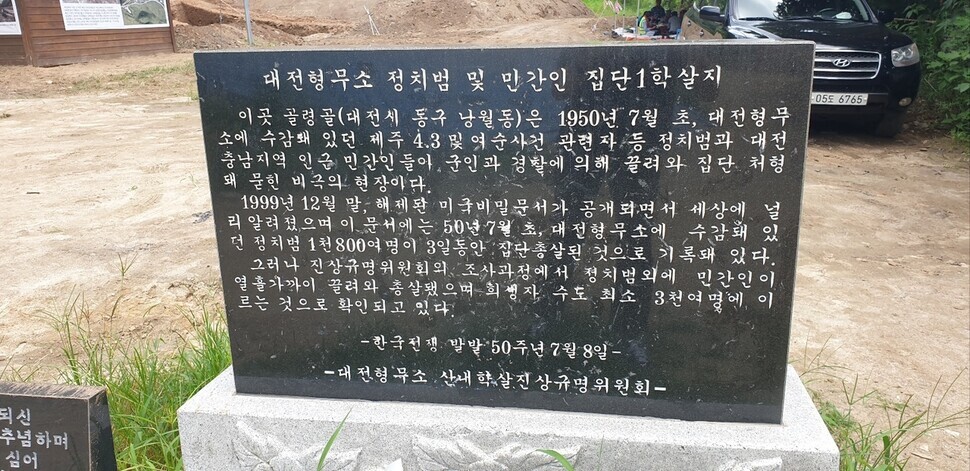

The first massacre of Gollyeong Valley — named so for the bones (“gol”) and spirits (“ryeong”) that fill it — took place between June 28 and 30, 1950, immediately after the outbreak of the Korean War.

Rhee and Defense Minister Shin Song-mo, along with other Cabinet members, had arrived in Daejeon on the morning of June 27. The next day, a portion of the inmates at Daejeon Prison — largely ideological offenders with ties to the rebellion in the Yeosu and Suncheon areas and members of the Bodo League who’d been taken into preventive detention — were led to Gollyeong Valley.

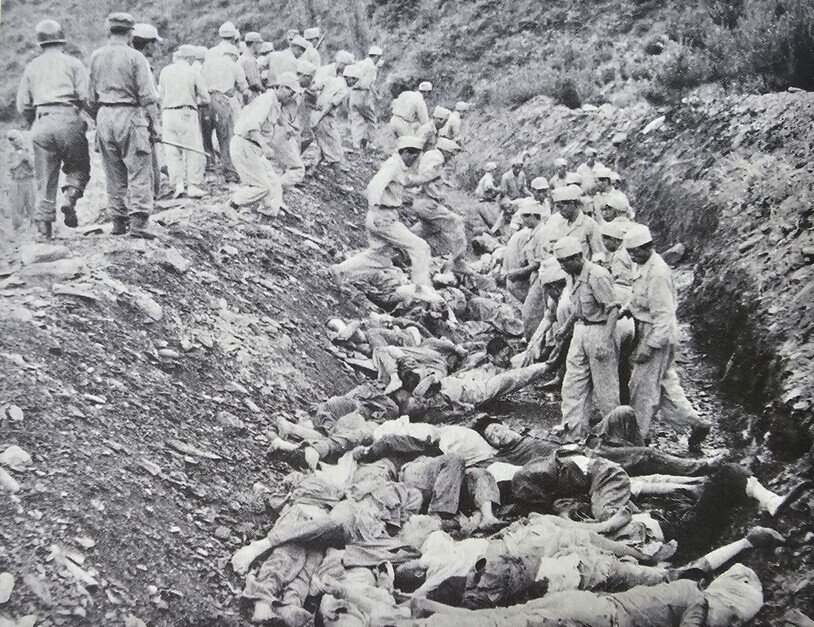

Located in the Nangwol neighborhood of Daejeon’s eastern Dong District, Gollyeong was a valley seldom visited by people. A member of the US Army Counter Intelligence Corps dispatched to Korea recorded in his war diary that 1,400 people had been shot and killed in the valley over the span of three days, starting on June 28.

In an interview with the press, a ranking police official gave the following testimony.

“Ten stakes were erected for executions, and the condemned were blindfolded and had their hands bound behind the wooden stakes. From 7 meters in front of them, the firing squad would shoot and kill them with M1s loaded with a single round each. When they [military police] shot upon their commanding officer’s orders, the heads of the condemned would slump. The commanding officer would then make confirmatory shots. Once the confirmatory shot had been taken, firemen would untie their hands and toss the bodies in a pile of firewood that had been prepared. Once there were 50 or 60 bodies gathered, they’d incinerate them.”

At dawn on July 1, 1950, Rhee covertly left Daejeon. That same morning, the Daejeon high prosecutor sent a telegram ordering that “left-wing radicals” be dealt their punishment. There were 4,000 inmates detained at Daejeon Prison at the time.

On July 2, the 2nd Division of the military police at the time requested that Daejeon Prison hand over leftist prisoners, including those jailed for violations of the Articles for the Government of Korean Constabulary and McArthur proclamation, those with ties to the rebellion in Suncheon and Yeosu, members of the Bodo League, and violent offenders with sentences of 10 or more years. The next day, the prisoners were taken to Gollyeong Valley.

The head of the Daejeon Prison’s special security unit gave the following testimony.

“We’d sit the prisoners on the ground and make them face the pit, then put [the gun] to the back of their heads and shoot. When I’d shoot them from the back, blood and white bits from their skull would splatter all over my pants. Before long, we were shoving the corpses in backward, so there’d be legs sticking up and all sorts of stuff. The commanding military police officer made the Youth Defense Corps go up into the mountains and roll down stones to press the bodies down.”

It is estimated that between 1,800 and 2,000 people were killed in this second wave of massacres that occurred over those five days.

Over all three rounds of slaughter, around 7,000 people were massacred in the valley between June 28 and July 17, 1950.

What led the military and police to perpetrate such hideous acts against their fellow South Koreans?

Even after the Japanese occupation ended, Daejeon Prison was filled with people accused of theft and ideological crimes. In the wake of liberation, antagonisms intensified between the left and right, and an increase in disturbances by people opposing the establishment of the single regime under Syngman Rhee led to more and more being detained.

Between March 1948 and 1949, the number of people incarcerated at Daejeon Prison jumped from 1,875 to 3,041. Some of these people were imprisoned in connection with the Yeosu-Suncheon rebellion and Jeju April 3.

On June 5, 1949, the Rhee regime had converted former leftists to join an anti-communist group called the Bodo League, also known as the National Guidance League. The league’s purported aim was to “protect and guide” leftists who renounced their beliefs. But government employees who cared only about the ends and not the means began indiscriminately including people who had nothing to do with left-wing ideology.

After the Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950, the Ministry of Home Affairs’ public security bureau sent out an emergency announcement to police bureaus nationwide instructing them to “detain all people under surveillance and reinforce detention center security.” Those affiliated with the Bodo League were detained at police stations, in township office storage facilities, and in prisons.

The first massacre occurred in Gollyeong Valley on June 28.

“If only I could exorcize my father’s bitterness”

Im’s daughter Nam-sin, who is now 73, has spent her life longing for the father who left for work one day and never returned. After hearing that Im had been “taken to Sannae,” his family members tried in vain to at least locate his remains.

Consumed with the search for his son, Nam-sin’s grandfather stopped eating. He fell ill and eventually passed away. The family’s fortunes declined, and Im’s wife remarried when their daughter was 12.

After growing up with her grandmother, Nam-sin married a man living in Daegu. She had come to detest Daejeon as the city where she had lost her parents.

After the launch of the second Truth and Reconciliation Commission in December 2020, Nam-sin requested an investigation into her father’s fate.

The first commission, which was launched in 2005, concluded in 2010 that “even if it was wartime, the state had an obligation to protect the lives and property of its people, and its execution of prisoners without lawful procedures — based solely on a history of left-wing activity or concerns about potential cooperation with the People’s Army — was a clearly illegal act.”

“Responsibility for [the massacres] lies with the state and Syngman Rhee, who was president at the time,” it added.

It came as a devastating blow to the family members, then, when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s current chairperson Kim Kwang-dong recently made remarks calling it a “severe injustice” for compensation to be provided for victims of mass civilian deaths illegally killed around the time of the Korean War.

As of now, construction has not yet begun on a planned memorial to civilian Korean War victims that was supposed to be built in Gollyeong Valley by 2024. Since 2007, a total of 1,441 bodies have been exhumed there.

Every June since 2000, the Daejeon Sannae Incident Victim Family Members’ Association and Daejeon Sannae Gollyeong Valley Countermeasures Committee have held memorial ceremonies for victims of massacres in the valley. This year’s event took place at Gollyeong Valley on Tuesday.

While attending the ceremony, Im Nam-sin wiped tears away as she observed a religious ceremony meant to pacify the souls of those unjustly slain. Neither Kim Kwang-dong nor Daejeon Mayor Lee Jang-woo attended that day. Since 2010, Daejeon mayors had sent yearly memorial messages; this year, there was none.

Weeping as she held up a photograph taken with her father when she was 100 days old, Im said, “I’ve lived my whole life longing for the father in this picture. I don’t think I can go to my grave until the truth behind my father’s unjust death is brought to light.”

By Choi Ye-rin, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 4Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 5BTS says it wants to continue to “speak out against anti-Asian hate”

- 6AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 7Noting shared ‘values,’ Korea hints at passport-free travel with Japan

- 846% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 9Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 10Ethnic Koreans in Japan's Utoro village wait for Seoul's help