hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

How Chun Doo-hwan seized power in a coup — and why it’s unlikely to happen now

The newly released film “12:12: The Day” depicts the coup orchestrated by Chun Doo-hwan and his military clique on Dec. 12, 1979. The film focuses on combat between the clique behind the coup and the forces attempting to stop it during nine hours from the evening of Dec. 12 until the early hours of Dec. 13.

How did Chun Doo-hwan, who at the time was a major general in charge of the Defense Security Command (DSC), manage to pull off that coup? To answer that question, we need to consider Hanahoe, as Chun’s clique was called, as well as Chun’s position at the head of the DSC.

Since the 1960s, measures with multiple redundancies had been put into place to prevent a coup in the Korean military. Those safety measures had been taken by then-President Park Chung-hee, who himself had come to power through a coup on May 16, 1961.

The core duties of the DSC, which Chun commanded, are to combat “subversion” — meaning a coup. In other words, its activities are meant to stop coups from happening.

The concept of the DSC’s anti-subversion activities is not a matter of finding and removing overthrow threats. It is about preventing those threats from taking shape in the first place by detecting and preemptively eliminating any signs of subversion or by tracking down and managing any conditions where the threat of subversion is viewed as a possibility.

To nip any potential coup threats in the bud, the DSC closely tracks the people officially and unofficially in contact with key military commanders and their activities. The landline and mobile telephone conversations of major military commanders are also monitored around the clock.

Park Chung-hee appointed DSC commanders whom he believed he could really trust. Chun Doo-hwan, who was the commander of the Republic of Korea Army’s 1st Infantry Division at the time, was the one appointed to the position in March 1979.

Chun had long been one of Park’s right-hand men. As a captain, he was selected by the then-general Park shortly after the May 1961 coup to serve as a civil affairs secretary for the office of the chairman of the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction.

If a coup does happen despite the DSC’s preventive measures, the forces in Seoul are to be quelled by the Capital Garrison Command — which was stationed on Seoul’s Chungmu Road at the time in 1979 — or the Special Warfare Command in Seoul’s Songpa District. These units are sometimes referred to as “counter-subversion units.”

This coup prevention and suppression system did exist on Dec. 12, 1979, yet it failed to stop the military clique’s rebellion. That’s because the ringleader behind the coup was Chun, command of the very DSC that was tasked with preventing coups.

In “12:12: The Day,” the DSC can be seen listening in on the military communication network and tracking and responding to the counter-subversion forces’ movements with ease. In effect, the clique abused the authority to monitor military communication networks — something given to the DSC to prevent coups — in order to actually carry out its own coup. The foxes had been left in charge of the henhouse.

The handful of Special Warfare Command and Capital Garrison Command leaders tasked with counter-subversion unit duties were the ones who headed the military rebels’ action groups.

Special Warfare Command commander Jeong Byeong-ju attempted to put down the rebellion, but his subordinates — 1st Special Forces Brigade leader Park Hee-do, 3rd Special Forces Brigade leader Choi Se-chang, and 5th Special Forces Brigade leader Jang Ki-o — betrayed him, pointing their gun barrels at their own superior officer.

What allowed these figures to defy the normal chain of command and their own duties to carry out the coup was the tight-knit private organization known as Hanahoe, meaning “association of one.”

Hanahoe was formed in 1963 as a private organization within the military in a process led by cadets from the 11th class of the Korea Military Academy, including Chun, Jeong Ho-yong, Roh Tae-woo, and Kim Bok-dong. On Dec. 12, 1979, Hanahoe members held key positions in the DSC, the Special Warfare Command, and the Capital Garrison Command.

Hanahoe originally styled itself as a kind of “bodyguard organization” for Park Chung-hee, growing its ranks under the president’s protection. The relationship between Park and Hanahoe was similar to that between a host and its parasite.

But when Park was assassinated on Oct. 26, 1979, the parasitic Hanahoe undertook a coup the following December to take over the host role for itself.

When he came to office as South Korea’s president in 1993, Kim Young-sam immediately went to work to eliminate Hanahoe.

Eleven days after his inauguration, he launched a blitz campaign on March 8 in which he removed military figures with Hanahoe connections: replacing the Army chief of staff and DSC commander, regulating the Hanahoe organization, and transferring those implicated in improprieties related to the Yulgok project to strengthen military strength, appointments, and the December 1979 coup.

Some derisively referred to the Hanahoe purge as a “surprise show.” Officials in the Kim administration insisted the measures were unavoidable under the circumstances at the time.

“The Dec. 12 coup happened when it was leaked in winter of 1979 that there were plans to make DSC commander Chun Doo-hwan commander of the East Sea Security Command. President Kim Young-sam could not help being concerned about this point. Early on in his term, there was almost no one he could trust among the generals appointed during the Roh Tae-woo administration. If the Kim administration wasn’t going to ‘cohabit’ with Hanahoe, it needed to eliminate it early on before it had a chance to marshal its capabilities,” said one reserve officer.

In an interview given after he left office, Kim himself said in August 1999 that he had eliminated Hanahoe as a measure for his own survival.

“If I hadn’t done it, there would have been no Kim Young-sam administration and no Kim Dae-jung administration. It’s clear they would have carried out a coup,” he said.

Indeed, speculation about a possible coup began swirling around intelligence agencies, the military, and the Blue House in the summer of 1993, the year Kim took office. Word was spreading that Hanahoe-affiliated generals who had been shifted into minor positions were divvying up roles for a future coup, including fund-raising and the mobilization of soldiers.

In response to these rumors, the administration began closely monitoring the telephone conversations and activities of the generals seen as likely to lead such a coup and the people close to them. It also combed through bank accounts looking for the sources of funds for the coup.

The rumors ended up just being rumors, but the speculation continued swirling through Seoul all the way through the end of 1993.

Until the mid-1990s, the specter of military intervention kept being raised when the political situation became uneasy. Various opinion surveys conducted around this time showed respondents naming the military as the group with the “most influence on South Korean politics.”

Since around 2000, however, South Koreans have tended to view a coup as out of the question.

The bigger factor is the transformation of South Korean society: more politically, economically and socially diversified and mature. It is no longer seen as being the kind of situation where the military could play the role of leader. Even if soldiers with political ambitions were to succeed temporarily in staging a coup and taking power, they would not be able to stay in power forever, and they would face punishments once their term had ended.

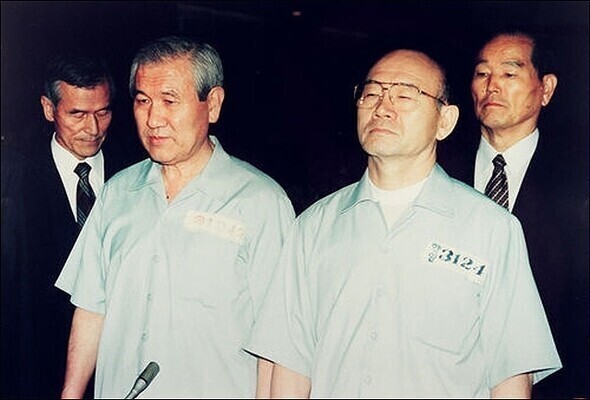

During the Kim Young-sam administration, prosecutors said of the December 1979 rebellion that a “successful coup cannot be punished.” After this provoked intense public resistance, the National Assembly moved in 1995 to pass the Special Act on the May 18 Democratization Movement, and Chun and Roh were indicted.

In April 1997, the Supreme Court upheld a life prison sentence for Chun and a 17-year sentence for Roh. A precedent for “punishing a successful coup” had been set. No longer are there private organizations with the military capable of carefully plotting and executing a coup in defiance of the official chain of command the way Hanahoe did in the past.

In the Kim Young-sam administration’s wake, the principle of civil controls on the military became the general trend. Civil controls are a framework where security policies are directed and decided by a popularly elected political figure (the president) and civilian official (the minister of national defense), while the military supports their decisions through military operations as a group of security experts.

A democratic military is a group of security experts who focus exclusively on their specific military duties, with the presumption of political neutrality. “12:12: The Day” reminds us once again that a democratic military and coups d’état are incompatible.

By Kwon Hyuk-chul, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 3[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 4Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 5Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 6Anti-immigration candidate marauds across Korea with squad detaining foreigners

- 7[Column] Unsettling moves by the UN Command lay way for Korean involvement in Taiwan

- 8Alleged drug use by Korean A-listers rocks nation – but not for the first time

- 91 in 3 S. Korean security experts support nuclear armament, CSIS finds

- 10[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art