hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Ideology wars, missiles and more: 10 Korean news stories that defined 2023

The controversy over the relocation of independence fighter Hong Beom-do’s bust at the Korea Military Academy was an example of the ideology-driven Yoon Suk-yeol government deliberately stirring up trouble where none had been.

In October 2022, Shin Won-sik — then a lawmaker for the People Power Party and now the minister of national defense — first argued for the independence fighter’s bust to be removed during the National Assembly’s parliamentary audit of the Ministry of National Defense

Arguments about the topic died down for a while before suddenly rocketing to the top of the Yoon administration’s to-do list this past August.

“Still rampant are anti-state forces that blindly follow communist totalitarianism, distort public opinion, and disrupt society through manipulative propaganda,” Yoon claimed in a speech given to mark the 78th anniversary of Korea’s liberation from Japanese occupation on Aug. 15, the Liberation Day holiday.

Ten days later, on Aug. 25, the Korea Military Academy announced that it would remove the busts of independence war heroes Hong Beom-do, Kim Jwa-jin, Ji Cheong-cheon and Lee Beom-seok, as well as the founder of the Shinheung Military Academy, Lee Hoe-yeong, from the academy’s main building and relocate them to elsewhere outdoors on campus.

On Aug. 28, when the controversy over the planned removal of Hong’s bust was heating up, Yoon visited a People Power Party dinner party, where he stressed ideology as being “the most important thing” and said that the country must be properly guided by philosophies rather than outdated ideologies.

Following Yoon’s declaration of war on history and his launch of ideological politics, the Ministry of National Defense stated that Hong’s affiliations with the Communist Party of the Soviet Union disqualified him from having his bust displayed “in a military academy that trains officers to fight North Korean communism.”

The Heritage of Korean Independence, an organization of independence fighters and their descendants, as well as opposition parties, argued that removing the bust of Hong is an “anti-constitutional action that denigrates the independence movement and denies the historical legitimacy of Korea’s armed forces,” but the ministry did not pay any heed.

The bust controversy snowballed into calls to rename a Navy submarine, to remove a bust of Hong from outside the Ministry of National Defense, and to revoke an honorary Korea Military Academy diploma that had been issued.

With Yoon’s emphasis on the people’s livelihoods after the ruling party lost the October mayoral by-election for Seoul’s Gangseo District, the Defense Ministry slowed its roll on attempts to remove the bust. Defense Minister Shin Won-sik said in November that he expected it to be “difficult” to move the bust of Hong before the year was up. “The process of convincing the public will take longer than expected, and the Ministry of National Defense has some preparations to make,” he said at the time.

This comes after the controversy over the bust of Hong became deeply etched in the public’s mind as a symbol of the Yoon administration’s ideological bias.

By Kwon Hyuk-chul, staff reporter

On July 19, a Marine corporal surnamed Chae was caught in raging waters while searching for people who had gone missing during major flooding in Yecheon County, North Gyeongsang Province. Chae was later found dead.

At the time, Chae had not been issued a life jacket. Col. Park Jeong-hun, head of the Marines’ investigation team, accused Lim Seong-geun, the head of the 1st Marine Division, of conducting the missing persons search without adequate safety measures and for issuing unreasonable orders.

Lee Jong-sup, the minister of national defense at the time, approved an investigation report containing the above information on July 30.

After that, outside forces began to pressure the investigators to exclude Lim and other parties from the list of accused in the investigation. Despite such pressure, the investigation team transferred the case to the police on Aug. 2.

The Ministry of National Defense immediately retracted the investigation report and charged Park with instigating an act of collective disobedience.

There are suspicions that President Yoon Suk-yeol was behind the strong-arming.

By Jung Hwan-bong, staff reporter

On July 19, a teacher at an elementary school in Seoul’s Seocho District took her own life. Suspicions were raised that abuse by overbearing parents was the trigger for her death.

Teachers called for measures to be taken, recounting their own experiences of facing malicious complaints from parents. Since July 22, tens of thousands of teachers gathered for rallies outside the National Assembly and Gwanghwamun in Seoul on Saturdays.

Teachers designated Sept. 4, which marked 49 days since the passing of the elementary school teacher, as a public education stoppage day and launched a walk-out by using PTO and sick leave.

In response to teachers’ demands, the National Assembly passed revisions to four laws to reinforce teachers’ authority in the classroom in September, protecting the teachers’ rights to give life guidance to students, and specifying the responsibilities of the head of schools.

Meanwhile, the country’s Student Human Rights Ordinance has been blamed for the decline in teacher authority, prompting local legislatures to move to abolish it.

By Park Go-eun, staff reporter

The beginning of the 2023 World Scout Jamboree, hosted on land reclaimed from the sea in Saemangeum on Aug. 1, was marred by a scorching heat wave and a lack of preparation. The event effectively came to an early close after a mere week on Aug. 8, due to the approach of Typhoon Khanun.

Despite the Jamboree being a massive international event with more than 40,000 participants from over 150 countries, Korea’s preparations were haphazard and inadequate. Heavy rains flooded campsites, participants complained of bug bites, and people were suffering from heat exhaustion as the camps were set up on reclaimed land that featured no natural shade. The state of poor hygiene in public facilities, such as the toilets and showers, went viral on social media.

As the public criticized the lack of preparation, the central government (the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family), and North Jeolla Province, the local municipality with jurisdiction over the region, placed the blame on each other, and the budget for the Saemangeum social overhead capital project was drastically cut.

By Park Im-keun, staff reporter

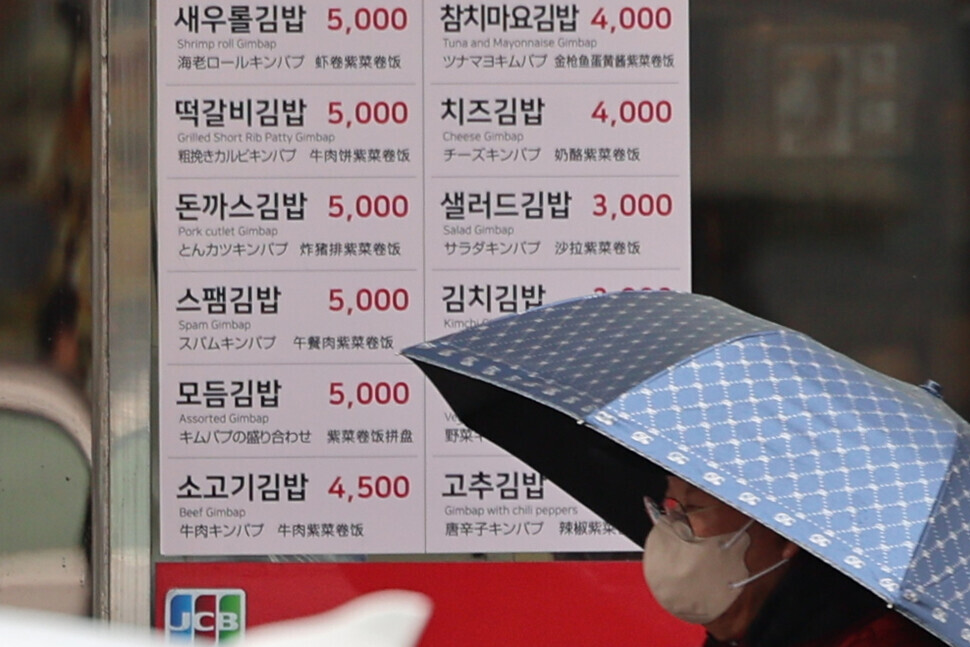

This year, ordinary Koreans fell on difficult times due to high prices and interest rates. The inflation rate for consumer goods soared to 6.3% (year-on-year) in July 2022 and has since dropped slightly in 2023, but is still above 3%.

The Bank of Korea doesn’t expect inflation to drop to 2.0% until late 2024 or the first half of 2025, meaning the painfully high prices won’t be going anywhere for a while.

As central banks around the world have been rapidly raising policy rates to combat high inflation, the burden on households to repay their loans is also mounting. In the second half of 2023, the upper limit of Korea’s four major banks’ floating interest rate for mortgages exceeded 7% per annum, and the higher end of the credit loan rate also jumped to the upper 6% range.

According to Statistics Korea’s survey of household finance and welfare, Korean households paid an average of 2.47 million won (US$1,900) in interest on loans for all of 2022. That interest payment is likely to be even higher in 2023.

By Jun Seul-gi, staff reporter

The inter-Korean military agreement signed at Panmunjom in September 2018 acted as a safety mechanism for peace by preventing and de-escalating military clashes, but these agreements are now void.

Within this year alone, North Korea conducted five intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) test launches: the Hwasong-15 on Feb. 18, the Hwasong-17 on March 16, and three separate Hwasong-18 launches on April 13, July 12 and Dec. 18. The three Hwasong-18 launches are particularly notable, as the missile utilizes solid fuel, meaning that North Korea has achieved initial operational capability of its ICBMs.

North Korea sent its first military surveillance satellite into orbit on Nov. 21. In response, South Korea suspended a portion of the Sept. 19 inter-Korean military agreement that established no-fly zones for reconnaissance aircraft and fighter jets near the Military Demarcation Line that divides the two Koreas. North Korea responded in kind by declaring the total nullification of the inter-Korean agreement. The two Koreas have regressed to the state of tensions that racked the peninsula before the Sept. 19 agreement.

By Shin Hyeong-cheol, staff reporter

7. People Power Party’s landslide defeat in Gangseo District

The People Power Party lost the seat for the Gangseo District Office chief in a by-election on Oct. 11, outclassed by a margin of 17.15 percentage points. Following the election, John Linton, the chairperson of the People Power Party’s innovation committee, said that certain party leaders, old guard and pro-Yoon lawmakers should not run in the general election in April 2024 — or at the very least run only in contested districts or opposition strongholds. Linton, however, got no immediate response from the party. In the end, the innovation committee was disbanded after changing nothing within the party.

Chang Je-won, one of President Yoon Suk-yeol’s closest allies, instigated an abrupt change in party politics by announcing on Dec. 12 that he will not run in April. Then party leader Kim Gi-hyeon, who had been denying rumors pertaining to his possible resignation, vacated his post after refusing to respond to the president’s demands that he withdraw from the general election. That left the People Power Party in a position where it would have to go into next year’s general election under interim leadership, and it responded by quickly recruiting Han Dong-hoon from his post as justice minister.

The resignation of former party leader Lee Jun-seok, Lee’s replacement by Kim Gi-hyeon, and Kim’s Hail Mary replacement by Han — all of this unfolded according to Yoon’s wishes.

By Son Hyun-soo, staff reporter

8. Democratic Party embroiled by Lee Jae-myung’s legal troubles

The year of 2023 as experienced by the Democratic Party can be summarized by the legal scandals surrounding party leader Lee Jae-myung. On Jan. 10, prosecutors alleged that corporate donations made to the Seongnam Football Club were in fact political bribes made to Lee. On Feb. 27, the National Assembly narrowly rejected a motion to consent to the arrest of Lee for corruption charges. On Sept. 21, this move was overturned when the National Assembly approved a secondary motion that allowed for Lee’s arrest. The results showed a number of dissenting votes within Lee’s own party.

Throughout the past year, investigations targeting Lee have practically swallowed up all other party affairs. Lee seems to be making a comeback, however. On Sept. 23, he ended a 24-day hunger strike in protest of the policies of the Yoon Suk-yeol administration. On Sept. 27, a Seoul court rejected an arrest warrant for Lee. On Oct. 11, the People Power Party lost the mayoral by-election in the Gangseo District. Yet despite such movements, Lee has maintained a passive posture regarding reform and communication.

On Dec. 13, Lee Nak-yon, a former prime minister and former party leader, announced plans to launch a new party ahead of the April general election. Once again, Lee Jae-myung must prove himself to the Korean public. Lee Nak-yon and members of the non-Lee Jae-myung faction of the party are now calling for Lee Jae-myung’s resignation as party leader.

By Um Ji-won, staff reporter

This year was rife with controversy and debate over issues regarding freedom of the press. Yoon dismissed Han Sang-hyuk this May from his post as chief of the Korea Communications Commission (KCC) after Han was indicted by prosecutors for targeting conservative media. Yoon then dismissed Jung Yun-joo from his post as chairperson of the Korea Communications Standards Commission (KCSC) in August. Both Jung and Han were appointed by the Moon Jae-in administration.

Having replaced KCC leadership, the Yoon administration then moved to separate TV licensing fees from electricity bills, which the KBS vehemently opposes. Yoon also moved to replace the board of directors and management for public broadcasters KBS and MBC, and to privatize YTN, in a rash of moves that shook the very foundations of public broadcasting in Korea.

When online news outlet Newstapa published its interview with Kim Man-bae, who linked a real estate development scandal directly to Yoon, the KCSC labeled the interview as “fake news,” further embroiling the Yoon administration in controversies regarding press freedom.

Under the Yoon administration, prosecutors have conducted controversial search-and-seizure raids on reporters from MBC and the Kyunghyang Shinmun, a liberal-leaning paper. The opposition-controlled National Assembly passed a bill to amend broadcasting laws to curb the Yoon administration's control over public broadcasters on Nov. 9, but the process was blocked by Yoon’s veto.

By Choi Sung-jin, staff reporter

This past May, a man in his 30s murdered his ex-girlfriend in Seoul’s Siheung neighborhood. After she broke up with him, he assaulted her. After she filed a report with the police, he took revenge by killing her. During the time lapse between her report to the police and her murder, the police did nothing to protect her from danger.

Two months later, another man in his 30s murdered his ex-girlfriend after stalking her extensively in Incheon’s Nonhyeon neighborhood. The court had slapped him with a restraining order, but it’d been ineffective.

This past August, a woman was brutally raped and murdered in Seoul’s Sillim neighborhood by another man in his 30s. She was on her way to work. Her killer, who was later identified as Choi Yun-jong, was a complete stranger to the victim. During police interrogation, Choi claimed that he “only wanted to rape her,” and did not intend to kill her.

In November, a young woman was violently assaulted by a man in his 20s while she was working a shift at a convenience store in Jinju, South Gyeongsang Province. The perpetrator’s reasoning was, “She had short hair, which means she’s a feminist. And feminists deserve to be beaten.” This past year was one of continuous violence toward women. Every day, countless women across the country are relieved that they’ve somehow managed to survive another day as they remain in the legal system’s blind spots.

By Oh Se-jin, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- 2Yoon’s broken-compass diplomacy is steering Korea into serving US, Japanese interests

- 360% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 4[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art

- 5After 2 years in office, Yoon’s promises of fairness, common sense ring hollow

- 6S. Korean first lady likely to face questioning by prosecutors over Dior handbag scandal

- 7AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 8[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- 9[Column] Why Korea’s hard right is fated to lose

- 10‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be