hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Migrants in South Korea are organizing for communities beyond their own

The migrant workers center in Paju was bustling with people when the Hankyoreh visited on May 12. After a few minutes spent chit-chatting with each other in their native languages, those gathered in the lobby all headed up to a room on the third floor for Korean class.

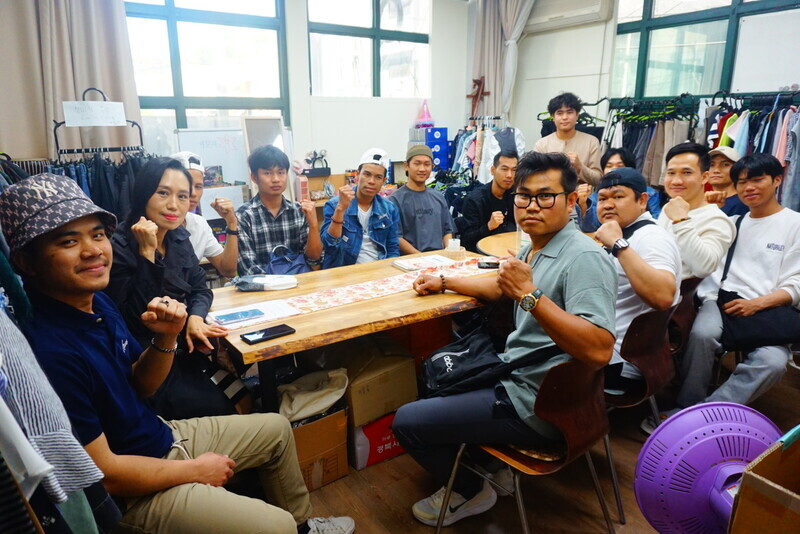

Like any local center for migrant workers, the halls of Paju’s Shalom House echo with a variety of non-Korean languages, including Burmese, Sinhala and Khmer. But there’s something special here. The migrants that frequent the center have formed various community gatherings according to where they’re from. At 3 pm on the day we visited, there was a meeting for people from Myanmar. There were many more Burmese arrivals than expected, and were suddenly searching for a bigger room.

“This community gathering started with just three people in December 2022. Now there are over 30 of us,” said May Moe Thu, 46, who organized the gathering.

Aside from Moe Thu, who arrived in South Korea as a marriage migrant, most of the community members from Myanmar are men in their 20s and 30s who arrived in the country on non-professional work visas (E-9). Most of the time, migrants come to the center seeking basic job consultations and Korean lessons, but the Burmese community is different. When the Hankyoreh visited, members were gathered to discuss ways to help people suffering as a result of the country’s military coup. They also discussed how they can help their local communities. Whether it’s local affairs, democracy, dialogue, or peace, no subject is taboo.

But they don’t just talk the talk. They walk the walk too. Literally. In April of last year, they took part in the march to commemorate victims of the Itaewon Halloween crowd crush. They also took part in a pilgrimage march to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) in March.

“This is about more than just making money as a foreigner in Korea and then going back. It’s about being a member of the local community here, sharing the pain suffered by both the Burmese and Koreans, and paving the path to coexistence,” said Moe Thu.

In addition to raising awareness among Koreans about the political situation in Myanmar, the community also does charity work for the Burmese people. In February, the group raised 5 million won (US$3,650) with the help of Paju citizens to travel to a Burmese refugee camp in Thailand. The group had scheduled a briefing about the visit for Friday, May 24, and is expected to announce plans for the future.

“Koreans experienced similar pain [from their own coup] in the past, so I think raising awareness about Myanmar’s situation helps Koreans and Burmese understand each other,” Moe Thu said.

Whether it’s Itaewon or Myanmar, the group is concerned about everyone.

“They are constantly discussing ways to be active in other regions,” said Lim Gyeong-ran, the secretary-general of Shalom House.

“Their activities contribute to the coexistence of migrants with locals,” Lim added.

“The community forms a culture of coexistence, and the community interacts with their surrounding community, and that local community forms a culture of acceptance. That’s the objective,” said Kim Hyeon-ho, a priest who volunteers at Shalom House,

Moe Thu worked as a travel manager in Myanmar. She was just an average person with an average job. She didn’t get involved in social issues. After she arrived in Korea in 2009, however, this changed.

“I never thought I’d become the activist type when I first arrived in Korea,” she said.

“One day, it just occurred to me that I wanted to do something to help Myanmar from here in Korea,” she added.

In 2021, Shalom House contacted her, and she began working there as an interpreter. Lim’s philosophy for Shalom House is that “the migrants are the leaders.” When Moe Thu started working for the center, it awakened something in her. In 2022, she took part in a candlelight vigil in Paju for victims of the coup in Myanmar.

“People gathered and started talking. Those talks around candlelight led to a Burmese community,” she said.

Moe Thu hopes her troubles can help pave a path for future migrant workers.

“I hope that migrant workers, through their community service, can form bonds with local Koreans and learn something in the process,” she said.

“I want to act as a bridge between the Burmese and Korean peoples.”

Shalom House also hosts community gatherings of people from Sri Lanka, Cambodia and Thailand. In fact, the Myanmar community gathering is new. All the other communities started out as groups of migrant workers, but each one develops its own character as it evolves.

“The Sri Lankan community was mostly single, unmarried workers in the past, but now it’s mostly people who have since married and started families,” Lim said.

This is the result of actively engaging with the surrounding community.

As the years roll on, it’s becoming more common to find migrants in their surrounding communities outside their enclaves. A key example is migrant worker centers working with public libraries to create community spaces like the Geumchon Rainbow Small Library. This library, managed by 11 migrants, many of whom are women who came to Korea for marriage, is specially operated for the sake of migrants. The library is a joint project between the Shalom House and the Paju Family Center. Moe Thu is one of the people who help manage the library.

“Everyone takes turns managing the library, forming a network that serves as the backbone of the community,” said Kim Eun-yeong, the main librarian.

Yurie Nakami, 37, who came from Japan, is also one of the library’s managers. She previously worked for Booksdot5 bookstore, which was operated by a cooperative in the city’s Gyoha neighborhood. As a member of Paju’s Panorama Choir, Nakami joined her two daughters in a choir concert held to honor the victims of the Sewol tragedy.

“When I first came here, I really felt like an outsider, but getting involved in the local community has made me feel like a Paju local,” she said.

The local library offers additional opportunities to engage with the surrounding community.

Taiwanese-born Jeon Yiru, 44, went on to become a certified librarian.

“Whether you’re Korean or foreign, we all have dreams,” Jeon said.

“We can latch onto that commonality to form bonds,” she added.

Sayaka Iizuka, 45, who’s from Japan, is getting ready to publish a children’s book.

“Books have allowed me to bond with Koreans, which is truly a joy,” she said.

“I write books to further strengthen those bonds. I want to become a storyteller who reads in front of large crowds,” she added.

The desire to live as part of a community that all these people held when they first arrived in Paju is steadily becoming a reality.

“It’s human nature for us to be afraid of and reject that which we don’t know,” remarked Gan Gahye, 36, from Taiwan. “But those emotions that people harbor toward outsiders isn’t so much hate as it is a type of fear.”

Gan expressed that it would be nice if Korea made more “welcoming spaces for migrants and Koreans to introduce themselves to one another.” Places like the Geumcheon Rainbow Small Library, which went from a place that many considered “only for foreigners” to a venue for Koreans and their migrant neighbors to share their thoughts about life and books.

By Lee Jun-hee, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0625/9617193034806503.jpg) [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

[Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order![[Editorial] Workplace hazards can be prevented — why weren’t they this time? [Editorial] Workplace hazards can be prevented — why weren’t they this time?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0625/7817193028141614.jpg) [Editorial] Workplace hazards can be prevented — why weren’t they this time?

[Editorial] Workplace hazards can be prevented — why weren’t they this time?- [Editorial] Seoul failed to use diplomacy with Moscow — now it’s resorting to threats

- [Column] Balloons, drones, wiretapping… Yongsan’s got it all!

- [Editorial] It’s time for us all to rethink our approach to North Korea

- [Column] Why empty gestures matter more than ever

- [Editorial] Seoul’s part in N. Korea, Russia upgrading ties to a ‘strategic partnership’

- [Column] The tragedy of Korea’s perpetually self-sabotaging diplomacy with Japan

- [Column] Moon Jae-in’s defense doublethink

- [Column] S. Korea-China cooperation still has a long way to go

Most viewed articles

- 1Blaze at lithium battery plant in Korea leaves over 20 dead

- 2Foreign day laborers make up majority of death toll in Korean battery factory fire

- 3[Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

- 4How sanctions are backfiring to fuel a new Eurasian alliance

- 5[Editorial] Workplace hazards can be prevented — why weren’t they this time?

- 6After Putin’s Pyongyang summit, Seoul and Moscow play dangerous game

- 7What made Korea’s lithium battery plant fire so deadly

- 8[Photo] K-pop: For everyone, everywhere

- 9Is Korea ready to protect the rights of Filipino domestic workers arriving this fall?

- 10[Editorial] Seoul failed to use diplomacy with Moscow — now it’s resorting to threats