hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] A worker’s body is stolen

By Hwang Ye-rang, Hankyoreh 21 staff reporter

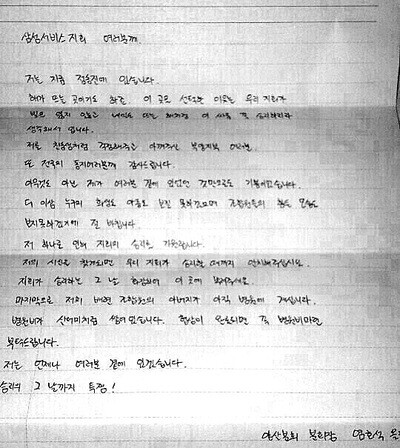

“I’m in Jeongdongjin now. When you find my body, please don’t bury me until the day our chapter achieves victory. On the day of our chapter’s victory, I want you to cremate me and sprinkle my ashes here.”

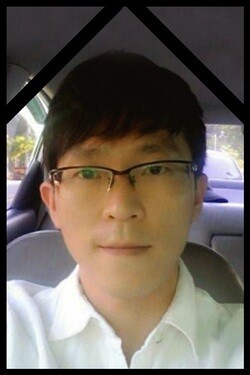

The note reads like a victory prayer for the labor union. In the space of just twenty lines, the word “victory” appears five times. The reason he chose to die in Jeongdongjin, the writer said, was because “I believe our chapter will be victorious in this fight, sure as the sun will rise tomorrow.” Jeongdongjin is on South Korea’s east coast and is famous for its beautiful sunrises, particularly on New Year’s Day. It was the final message of Yeom Ho-seok, who was found dead at age 34 on May 17 in a parked car on a road near Jeongdongjin, Gangwon Province. Yeom was head of the Yangsan Service center branch of the Samsung Electronics Service labor union, a chapter of the Korean Metalworkers’ Union.

23 Years Later: Police take another worker’s body

Yeom’s final wishes could not be kept. On the evening of May 18, around 250 riot police stormed into the Gangnam branch of Seoul Medical Center, where his body was lying in state. An intense fight ensued with the union members who were watching over his memorial; even tear gas was used. Around twenty people were arrested, including senior deputy chapter head Ra Du-sik. Yeom’s body, closely guarded by police, was loaded onto an ambulance. Instead of Jeongdongjin, it was taken to Busan. It was the first example of police forcibly seizing a dead body since 1991, when the body of Hanjin Heavy Industries and Construction Park Chang-soo was taken. Park committed suicide protesting his layoff.

Jeon Hae-jun, a member of the Samsung Electronics Service chapter, related the events that unfolded.

“On the evening of May 17, Yeom Ho-seok’s father signed a document giving the union power of attorney for all of the funeral procedures,” Jeon said. “He told us he had met the Yangsan service center chief and some people from Samsung headquarters at the Danyang rest area in North Chungcheong Province, on the way up from Busan to Gangwon. At the meeting, they suggested compensation, saying they would pay for the funeral, and he told them, ‘I should probably look at my son’s body first.’ But on the afternoon of May 18, after he arrived in Seoul, he suddenly changed his mind and said he wanted a family funeral. The two friends who came with him from Busan stopped him for talking to the labor unionists. Then he went out for an hour or two in the morning - he might have met with Samsung.”

Finally, the family called the police at 112 (the non-emergency number) to request the body, at which point the police sprang into action. A unionist said members were on their knees before Yeom’s father asking to be allowed to honor the son’s dying wish.

“I just don’t understand how this warranted the police seizing his body,” a unionist repeatedly said.

When the Hankyoreh reporter arrived just after 9 pm on May 18, there were 100 or so unionists sitting despondent in front of Seoul Medical Center funeral home. With them was Lee Mi-hee. Her husband, a repair technician at the Cheonan center, took his own life last October. Before committing suicide, he left a message in a chat room with union colleagues on the Kakao Talk instant messaging service. “It’s been so hard working at the Samsung service center,” he wrote. “I’ve been so hungry I couldn’t stand it, and it’s been tough seeing the way everyone else is struggling. Maybe I can’t do it the way Jeon Tae-il [a labor activist who committed suicide by self-immolation in 1970] did, but I’ve made my decision. I just hope it helps.”

Yeom’s suicide was the third death in less than a year after the Samsung Electronics Service chapter was launched in July 2013. That August, a union member at the Chilgok center named Im Hyun-woo died of overwork.

“There was a note, and it was a decision that Yeom made,” said Lee. “Now that he’s gone, that doesn’t mean the family can just do whatever they want. And the police just take things too far.”

Yeom’s father remained unmoved by the heartfelt pleas of people who shared his son’s plight.

“I tried telling him, ‘Your son died because of Samsung. You don’t have any reason or anything to gain from taking his body away,’” one said. “It didn’t do any good.”

Hwang Sang-ki, whose daughter was a Samsung Electronics semiconductor worker before dying of leukemia in 2007, stood in front of the funeral home for a long while, seemingly unable to move.

The police’s seizure drama didn’t end there. Two days later, another intense fight broke out on May 20, with 100 union members scuffling with 300 police over Yeom’s funeral urn in front of the Miryang Public Crematorium in South Gyeongsang Province. Also present was Yeom’s mother, surnamed Park, who had lived apart after she and the father divorced when Yeom was six. Despite her screams to let her son’s dying wishes be honored, the police left the scene with the urn.

Beforehand, Yeom’s union colleagues from Busan and South Gyeongsang had been forced into a game of hide-and-seek prior to locating and arriving at the crematorium. They had gone to the funeral home at Haengrim Hospital in Busan, only to find out belatedly that only Yeom’s funeral portrait was there, while his body had been enshrined elsewhere. They were forced to hastily check the schedules of nearby crematoria. The family had told the union the coffin would be taken out on the morning of May 21, but reservations were set for two different crematoria on the afternoon of May 20.

“The family and the police asked us to keep things quiet,” admitted a source at Haengrim Hospital on condition of anonymity.

“But it’s what the family wanted, to have the body somewhere else other than he hospital,” the source added.

Now the union has no way to know just where Yeom’s urn ended up.

The family and police’s attempts to circumvent the union were nothing sort of an intelligence operation. Would the authorities have moved so quickly if it had been a request by just one family member? Attorney Kwon Young-guk, co-president of the Correcting Samsung Campaign Headquarters, said the police “did more than just protect Samsung; they did Samsung’s work for them, like Samsung employees.”

“Faced with a person’s death, they responded not with condolences or remembrance, but with threats, insults, and violence,” Kwon continued. “We need to get angry about the way they used state force in a family affair, even when the mother was there making her own strong case to keep her son’s wish. We need to bring the truth to light about how Samsung was involved and how the police cooperated with them.”

At the moment, all allegations of Samsung’s involvement are based on conjecture rather than evidence. Samsung Electronics Service has said it has “no reason to meet with the family and no need to get involved” in matters between the Yangsan center and the family. Its position is that the issue is something for its subcontractor and its employees to resolve with the family members.

Yeom Ho-seok went to work at Samsung Electronics Service in June 2010. He was a repair technician providing service on a range of Samsung Electronics products, including refrigerators, air conditions, notebook computers, and mobile phones. He wore a uniform with the Samsung Electronics Service logo, but his employer was actually a company that had a contract with Samsung Electronics Service, which is an affiliate of Samsung Electronics. He had no fixed salary; his pay was based on commissions for the repairs assigned from the call center. In slow months, he might work from morning until late at night and take home just 800,000 to 900,000 won (US$780-880), after subtracting costs for car maintenance - an essential expense for someone making house calls. Fed up, he left the company in 2012, but returned in February 2013.

When the labor union was established in July of that year, Yeom was chosen as the Yangsan union branch head. He was already almost broke, and going on strike made his bank account even emptier. According to the union, the recent strike brought Yeom’s paycheck down to 700,000 won in March and 410,000 won in April.

The Korean Metalworkers’ Union and the Korea Employers Federation (KEF), which was representing 40 subcontractors for Samsung Electronics Service, had been negotiating the introduction of a monthly salary system since the end of 2013, but there had not been any noticeable results. At the end of April, the union announced that negotiations had reached an impasse and called a strike.

The KEF is calling for negotiations to be resumed. “In the Seoul-Gyeonggi Province area, we had reached a tentative agreement on 73 out of 126 areas of dispute. But the union representatives suddenly stormed out of the discussion, calling for direct negotiations with the presidents of each individual subcontractor,” said a KEF representative on condition of anonymity.

As the strike dragged on, it became more and more difficult for Yeom and the other union members to get by. Park Jeong-ae, 45, secretary of Busan’s Gwangan Center union branch, spoke with a Hankyoreh reporter on the evening of May 20 at a memorial service for Yeom that took place in front of the Samsung headquarters in Seoul’s Seocho district.

Park explained that she had been like a “big sister” to Ho-seok. They would see each other every week at the meeting for the South Gyeongsang region, and Yeom - an only child - would always stick close to Park. During recent phone calls, whenever Park asked Yeom what he was doing, he would say he was just sitting around.

When someone calls the Samsung Electronics Service customer service hotline (1588-3366) asking for repairs, receptionists like Park put the caller in touch with a repair technician who has an opening in their schedule. But when employees open the schedule of technicians like Yeom who are active in the labor union, a message pops up instructing them not to call them with work, Park said. This is a repressive measure taken to bust the union.

“It seemed like Ho-seok was doing a part-time job from Thursday to Saturday when there was no protest in Seoul. When I asked him if he was driving a taxi, he just said, ‘If you find out, it will just make you upset, so don’t try to find out.’ He was a really deep kind of guy,” Park said. She only had a vague suspicion that he must be several million won in debt.

At the beginning of 2014, some union members were let go when the Haeundae (in Busan) and South Chungcheong Asan centers suddenly announced that they were closing their doors. Since the union branches had been active at those centers, suspicions were raised that the closings had been faked.

The last time that Park saw her “little brother” was the night of May 14. They had held an outdoor sit-in protest in front of Samsung Electronics headquarters in Seoul for three days and had pulled into a rest area on the highway on their way back to Busan. Yeom waved at her and said he would see her at the next Seoul demonstration. But she never saw him again.

Joining around 1,000 union members with the Samsung Electronics Service union chapter, Park stretched out her sleeping bag in front of the Samsung Electronics headquarters once more on May 19. It was the exact spot where Yeom had been laying a few days prior. This time, the outdoor demonstration was set to continue indefinitely. During the day, the unionists went around the city, drawing attention to Samsung’s no-union management policy and the labor rights of repair technicians working for Samsung Electronics Service. The union was contending that the subcontractors were actually disguised subsidiaries that Samsung Electronics Service had set up to cut costs, and that the real employer of the workers at these subcontractors was none other than Samsung Electronics Service. Samsung Electronics has around 180 service centers altogether; except for 800 employees working at service centers that are directly run by the company, the rest of the repair technicians - a total of around 10,000 - are irregular workers.

A final decision has yet to be made about the extent of Samsung’s legal responsibility for these workers. In Sept. 2013, the Ministry of Employment and Labor published a report concluding that the company’s activities do not constitute illegal dispatching. The Ministry drew this conclusion because the prime contractor, Samsung Electronics Service, did not appear to have the authority to give direct orders or commands to the repair technicians.

The union countered by filing a civil suit against Samsung Electronics Service, asking the court to recognize the status of the workers. At present, a lower court is reviewing the case, and it will likely be several years before a final decision is made. In the case of in-house subcontractor workers at Hyundai Motor, the prosecutors argued that they had not been illegally dispatched, but the court found that the workers were in fact employees of Hyundai Motor.

As for inappropriate action taken by subcontractors to prevent workers from joining the union, the Gyeonggi Province local office of the Ministry has recommended to the Suwon office of the prosecutors that it should bring charges against company representatives.

The members of the Samsung Electronics Service union chapter, who have lost Yeom Ho-seok in addition to Choi Jong-beom, feel desperate and angry.

“I’ve been working at this company for 20 years, and not a single thing has gotten better during that time. Not only the repair technicians, but even the office workers, are only paid commission for work that is done. This means that they aren‘t paid for the day’s work when the weather is poor. We don’t even get half the commission of employees at subcontractors for LG Electronics, our competitor,” said a unionist.

What compels these unionists to spend night after night on hard asphalt? What drives them to lay down their lives? Park Jeong-ae explained that they are trying to pay Samsung for all the ways that it has wronged them.

“There is a clear difference between the issues that Samsung must address and the issues that it cannot address,” a representative with Samsung Electronics Service said when asked about this. “While we might be able to help out the subcontractors, we cannot get involved in the issues of wages or in negotiations between the Metalworkers’ Union and the KEF, since we are not the direct employer.”

The police that went off with Yeom’s body and later with the urn arrested three union leaders. Ra Du-sik was apprehended at the funeral home on May 18 for interrupting a funeral and blocking public officials from carrying out their duties; chapter head Wi Yeong-il and Yeongdeungpo chapter head Kim Seon-young were seized in the demonstration in front of the Samsung office on May 19 for violating Assembly and Demonstration Act and for blocking traffic on a normal road. The arrests are further fueling the union’s resolve to carry on the fight.

“The world should not be like this. You took from us even the body, even the last words, even the remains of the dead. But the body of a man is not the only thing you have taken. You have lacerated all of our hearts. [. . .] The government that could not find the bodies we wanted [as in the case of the Sewol] it to find plundered the mortuary. These were not the officers of the state; they were no more than the mercenaries of capital.”

This was part of a poem recited by the poet Song Kyung-dong at the memorial service held in front of the Samsung main office on the evening of May 20.

“Today, we must leave you here, but tomorrow we said we will go with your friends to Jeongdongjin, where the sun rises. There is no longer anywhere else for us to go but Jeongdongjin,” Song’s poem continues.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 5[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 6[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 7Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 8All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 9More South Koreans, particularly the young, are leaving their religions

- 10John Linton, descendant of US missionaries and naturalized Korean citizen, to lead PPP’s reform effo