hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Former prisoners request retrial in Jeju Uprising cases

Attorney Im Jae-seong: Do you remember where you went for the trial?

Kim Pyeong-guk: Do you think I was looking up? They said I was a criminal, so I kept my head down and followed them. I went inside and saw three soldiers standing there, going back and forth around a seat that was kind of high up. There was a banner hanging there. “Article 77: Rebellion.” That one thing I remember.

Im: How many people were tried with you?

Kim: If I had to guess from what I saw, it was just short of around 100 people.

Im: You said there were soldiers in front.

Kim: They were a bit high up and walking back and forth. We were being “tried,” but they weren’t calling up criminals and announcing our names or asking us what crime we were accused of or what day it was. I saw what was written there and thought, ‘We’re being punished for rebellion,’ and then they said it was over and told us to go. I don’t know what it was – a trial or whatever it was.

Im: When did you hear about the sentence?

Kim: They brought over rope and tied people in up in groups of five, then loaded us into boats and sent them to Jeonju Prison. I felt frustrated not knowing how long I was going to be in there for, and the guard said “one year.”

Dragged off by police in Dec. 1948 for “a trial or whatever it was,” then 18-year-old Kim Pyeong-guk had no lawyer by her side. There was no questioning by a judge to confirm her identity, no reading of charges by the prosecutor, no sentencing request or ruling. Fearing for her very life, Kim could not even raise her head to look up.

Now 88, Kim stood in a proper court for the first time on Mar. 19. An attorney stood across from her as her wheelchair was secured in the witness stand. Seated to her right were three judges who would listen to what she had to say. In addition to a prosecutor, there were also fellow April 3 Uprising prisoners, support group members, and others in the gallery to support her. Kim described herself as “very nervous” before the trial.

“Now that I’m on the witness stand, I feel like I should just relax and say what must be said,” she said. Seventy years later, she delivered detailed testimony before the court on the events that took place on “those days.”

The second criminal division of Jeju District Court under Hon. Judge Jegal Chang heard testimony that day from Kim and three other petitioners for the second examination day on the retrial request for former prisoners in connection with the Jeju Uprising of April 3, 1948. The prisoners were sentenced to incarceration at prisons across South Korea by two general military tribunals on Jeju Island in Dec. 1948 and July 1949 on charges of rebellion (Article 77 of the old criminal code), aiding and contacting the enemy (Article 32 of the Defense Security Act), and espionage (Article 33 of the Defense Security Act).

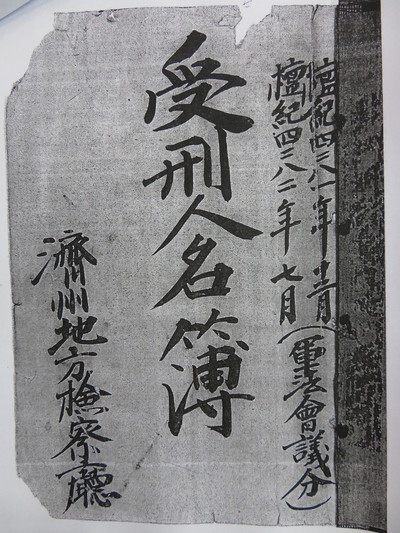

The only record of them is a list of prisoners that includes 2,530 names together with their legal domicile, verdict, sentencing date, and incarceration site. The listing under Kim Pyeong-guk’s name reads “Sentencing Date: December 5, 1948; Plea: Not guilty; Verdict: Guilty; Sentence: One year; Incarceration Site: Jeonju.” Kim was one of 18 former prisoners in connection with the Jeju Uprising who requested a retrial in Apr. 2017 to “restore our reputations.”

“They said taking refuge was the only way to survive, so I had gone down to the Namwon area in Jeju City,” Kim said. “The police came by one day and told everyone from the mountain village to come out. I had no idea what it was about, but I was taken away with my mother and two siblings. For three days, I was beaten like a dog by the police. It was indescribable.”

The other witnesses testifying alongside Kim that day – 86-year-old Hyeon Chang-yong, 85-year-old Oh Hee-choon, and 89-year-old Bu Won-hyu – were all captured by police at ages between 15 and 19, sentenced to one to five years in prison at military trials in Dec. 1948, and sent to prisons in Incheon and Jeonju.

”I wonder if I have anything left but to wait for death”The military trials of Dec. 1948 were carried out by brute force and with a disregard to legal protocol over the course of the Jeju Security Command’s decree on Oct. 17, 1948, pinning responsibility for the uprising on civilian residents of upland villages, and the large-scale massacre of residents by the military and policy to “suppress armed groups” after President Rhee Syng-man’s Nov. 27 martial law proclamation. Despite her innocence, Kim chose to marry far away out of “shame over having been in prison.” Only recently did she feel comfortable enough to request the retrial and clear her name.

“Had I done this trial when I was 40, 50, 60, I would have had freedom in my heart,” she said. “But at that time, I couldn’t go around with the word ‘prisoner’ attached to me. Now, no matter how good the trial outcome is, I wonder if I have anything left but to wait for death. It feels so unfair.”

These were the words delivered by Kim to the court as she concluded over 30 minutes of testimony.

By Kim Min-kyung, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 1In rejecting statute of limitations defense in massacre case, Korean court faces up to Vietnam War a

- 2Historic court ruling recognizes Korean state culpability for massacre in Vietnam

- 3“Those souls can rest now”: Vietnam massacre survivor reacts to Korean court win

- 41 in 3 S. Korean security experts support nuclear armament, CSIS finds

- 5[Editorial] Verdict on Korea’s massacre in Vietnam a first step in atonement

- 6Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 7Bills for Itaewon crush inquiry, special counsel probe into Marine’s death pass National Assembly

- 8Ruling on Korean atrocity in Vietnam comes 23 years after Hankyoreh 21’s exposé

- 9[Interview] Continuing the fight for victims of civilian massacres during Vietnam War

- 10Korea’s atrocities in Vietnam, in the words of those who saw and survived them