hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

A campaign by Jeju residents for proper food

“Imagine how famished the people of Jeju were at the time of liberation. There wasn’t any food to eat on Jeju Island. We needed the US military administration to give us rations to survive, and what we got from them was Western snacks. So we blocked the chocolate and demanded the distribution of food rations.”

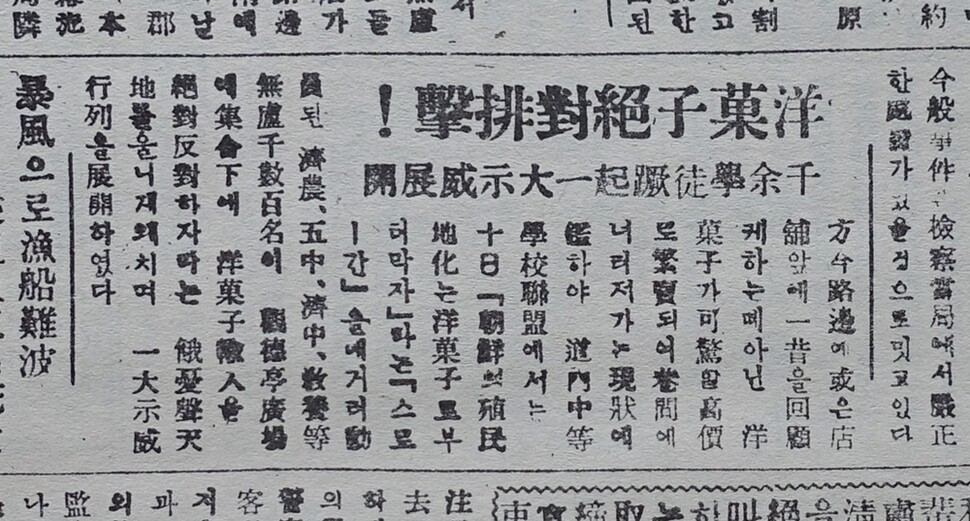

The campaign against Western snacks by Jeju students in early 1947 during the US military administration became tied to the issue of food rations, spreading through the island as it met with a positive response from other residents.

Hyeon Jeong-seon, one of the main figures in the movement, opened up about the campaign against Western snacks. Now a 91-year-old Tokyo resident, Hyeon, a native of the Jeju village of Hamdeok, was a 20-year-old third-year student at the six-year Jeju Agricultural Middle School at the time.

“During the Japanese occupation, students at the agriculture school would go into the farming villages as rice delivery supervision workers and watch their parents and siblings hand over the grains they had worked so hard to produce,” Hyeon explained in a January interview with the Hankyoreh in Tokyo.

“Their food was taken away from them, and the residents were starving. It’s because of that experience that I joined the opposition campaign when US snacks began arriving instead of rations after liberation,” he said.

“Around ten or so student representatives would travel in trucks. There were representatives from Jeju Junior High and Ohyun Junior High, and I was there as a representative of the agricultural school. In every village, we’d stop the trucks and give speeches holding microphones made of paper. We’d say things like, ‘We are not beggars.’ ‘Let’s stop eating Western snacks.’ ‘Ask for food to eat.’”

Even though he’s in his nineties, Hyeon could still clearly recall the experience.

Nationally, the snack matter was viewed as a serious domestic economic and social concern for both left and right. Social groups on both sides issued statements in Jan. 1947 to oppose the importation of Western snacks. Calling on the public to stop eating the snacks, they published messages recalling “the ruining experience of eating the jawbreakers that arrived with the ‘New Enlightenment.’”

“The US wants to develop Joseon [Korea] into a market for its products. Snack foods may be sweet, they have nothing to do with our prosperity and independence,” one statement said.

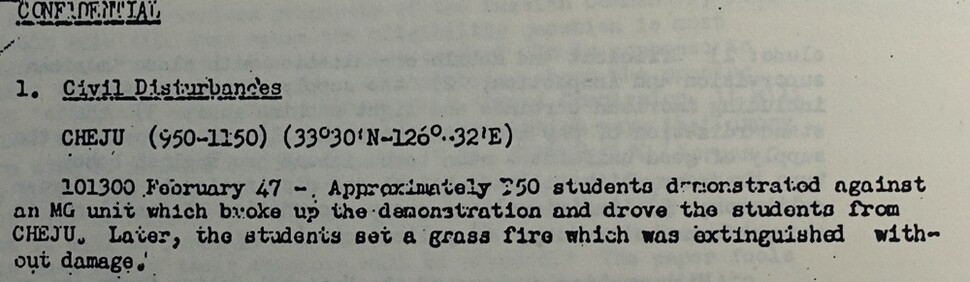

A student alliance representing secondary schools in Jeju staged a demonstration against snack imports on Feb. 10, 1947, at Gwandeokjeong Pavilion Square in Jeju City, home of the offices of the US military administration in Jeju. “Let snacks be the start to stopping the colonization of Joseon,” went their slogan. A US military intelligence report stated, “Approximately 350 students demonstrated against an MG unit which broke up the demonstration and drove the students from Jeju.”

“I was standing at the front when we held the demonstration in front of the US military administration office. The US troops had mounted machine guns on jeeps to threaten us,” Hyeon recalled. “We couldn’t advance any further because they might start firing.”

Shortly before the anti-snack campaign, students at Jeju Agricultural Middle School held a joint strike in the second half of 1946 oppose “imperial Japanese holdovers” and “fascism” in education.

“We were not on good terms with the students a year ahead of us,” Hyeon said. “The bad habits of the Japanese occupation had been carried over, and they beat the younger students a lot. So we gathered at Sarabong Hill in Jeju City and held the so-called ‘Sarabong meeting,’ where we began our student strike.”

From an army of “liberation” to one of suppression

For Hyeon and his compatriots, the arriving US forces were a “liberation army.” The first landing of US troops on Jeju came on Sept. 28, 1945, 44 days after Korea’s liberation. On that day, a surrender acceptance team with the US XXIV Corps arrived on Jeju to attend a surrender signing ceremony at Jeju Agricultural School with the command of Japan’s 58th Army stationed on Jeju Island. “We thought it was a liberation army, and we made American flags and went to welcome them, but the US troops took a different route and passed us by,” Hyeon said of the students at the time.

“We looked at the US troops as a liberation army, but over time we began butting heads with them. We started to think, ‘It’s strange. They said they were liberating us, but these are the things they’re doing,’” he recalled.

During the anti-snack campaign, Hyeon was arrested by police while putting up leaflets. He was detained and subjected to the so-called “turban shell smashing” torture, in which he was forced to kneel on tiny fragments of shattered turban shells while his knees were stepped on. Later, he was arrested by national defense security agents while distributing leaflets about a general strike on Mar. 10, 1947, in protest of the deaths of six people when police opened fire at a rally on Mar. 1 to commemorative the Mar. 1 independence movement. He subsequently went on the run.

Fleeing to Japan to survive

After about 20 days after hiding underneath the floorboards of a relative’s house in Jocheon township, Hyeon was visited one evening by his mother from Hamdeok township, who had asked around about him.

“Follow me,” she told him. “You’ll die if you stay here. You have a brother in Japan, and you’ll be able to eat if you go there.” Embarking in the middle of the night, he followed his mother and boarded a smuggling boat at the Hamdeok port. It was the last time he ever saw her. While in Japan, he heard from other hometown natives arriving secretly by boat about the horrific events of the April 3 Uprising in Jeju. His brother and nephew were among those killed.

Hyeon stayed for a little over two years in Osaka, where his brother lived. From there, he went to Tokyo, where he majored in engineering from a Japanese university and ran a plastic manufacturing business.

“Fate is a funny thing. One of my older friends in Tokyo was running a Western snack business. It was by working there part-time that I was able to go to university, and I ended up becoming the owner.”

“After all my talk about how ‘we are not beggars,’ how ‘we have our pride,’ I made my living off of Western snacks,” he laughed.

Returning home after 54 years

A long 54 years after departing Jeju in secret, Hyeon set foot on his home soil in 2001. He also visited Jeju in 2008 while events were being held to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the uprising; during his visit, he stopped at Jeju April 3 Peace Park to see where the memorial plaques had been enshrined.

“When I went to the memorial site, I found that some people had been recognized as victims and given plaques, while others had not. You can’t talk about ‘fully resolving’ the April 3 issue and then discriminate in your treatment of the victims. Everyone should be honored as victims.”

Will Hyeon’s wish come true someday?

By Huh Ho-joon, Jeju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong? [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/8517133419684774.jpg) [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?![[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0417/6817133413968321.jpg) [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

Most viewed articles

- 1Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 2[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 3[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 4Why Israel isn’t hitting Iran with immediate retaliation

- 5[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 6S. Korea, Japan reaffirm commitment to strengthening trilateral ties with US

- 7Japan officially says compensation of Korean forced laborers isn’t its responsibility

- 8[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 9[Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- 10[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters