hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

An elderly woman’s terrifying memories of being tortured by soldiers at 12 years old

“When the rats came into the cellar looking for rice, the cat would run over my back after them. While it was scary enough just being in that cellar without any electricity, what was even more frightening was the rats and cat running around on top of me. It made me shudder, as I hunched down there by myself.”

On Oct. 20, I visited Gangjeong Village, Seogwipo, on the 7th section of the Jeju Olle Trail, to meet Chung Sun-hui, 82. This was my second time there, following an earlier visit in May. Chung was trimming the tree branches in her yard. Even though 70 years have passed since the Apr. 3 Jeju Uprising of 1948, when Chung was 12 years old, even today she can’t shake the terrifying memories of being tortured.

In an attempt to flush out 17-year-old Chung Dong-ho, Chung’s second oldest brother, soldiers surrounding their house took one of her older sisters to the nearby Beophwan Police Office and took Chung to Gangjeong Elementary School. Chung was locked up in a cellar in a straw-thatched house in front of the school. One of the rooms in the house, which was barely 30m2 in size, housed a group of soldiers (members of the Northwest Youth League), while the other room was where they tortured her. The soldiers inflicted awful pain on Chung because someone had claimed to see her and her sister hiding their brother and bringing him food.

Electricity and water used to torture a 12-year-old girl

“They would bind my legs, back, chest and arms with thick ropes and then tie me to the door. Then they would turn me upside down and pound me into the ground. What do you think happened to my head? My hair fell out and I got a bald spot here,” Chung said, rubbing the top of her head. The soldiers would also use a teapot to force water into Chung’s nose and mouth.

“When they poured water into my mouth, I wouldn’t be able to breathe for so long I thought I was going to die. They would stick a skewer into my teeth and force my mouth open while telling me to speak the truth. For a long time after that, I had to do without two teeth,” she said. Deep wrinkles lined the woman’s face as she showed me her teeth and reenacted her experience.

“It gets better. When my stomach began to fill up with the water, they would push down on my stomach and knock the wind out of me. Then they would fill a bucket with water and splash it over me to bring me back to consciousness.”

The soldiers also used electricity to torture the Sun-hui. “It gets better. They prodded my legs with a bamboo stick with a buzzing piece of metal on the end that sent pus streaming down my legs. They would jab my breasts and shoulders, too, which made them swell.” Chung repeatedly used the sarcastic phrase “It gets better” to indicate that her torture greatly grew more and more intense.

In the winter of 1948, there was an unusually heavy snowfall on Jeju Island. Exhausted from the torture, Chung could see the outside world blanketed in white through the crack in the cellar door, which let in a chill draft. The cold made things even more painful for her. Despite the winter cold, Chung’s torturers left her in thin clothing that was sopping wet. The only thing she had to eat was a rice ball, the size of a child’s palm, which they would toss her once a day. Her sister, three years her senior, who had been taken to the Beophwan Police Office was subjected to similar torture.

A narrow escape from death

Chung and her sister had been taken into custody on Nov. 21, 1948, shortly after their older brother, a middle school student who had been recruited for road repair work at nearby Jungmun Village, had gone missing after being beaten and shot by soldiers from the Northwest Youth League.

“My brother and five boys his age got in a truck. When one of the boys said with a laugh that he’d never ridden in this kind of truck before, one of the soldiers hit him with the butt of his gun for laughing at them. When my brother tried to intervene and said there was nothing wrong with a kid laughing, the soldiers called him impertinent and began beating him with the butt of their guns. When the truck reached a steam near Jungmun Village, my brother jumped off the bridge, and the soldiers kept firing at him until they ran out of bullets. I never saw my brother after that,” Chung said.

The boy in the truck who had laughed came to visit Chung later and told her that her brother had died on his behalf. That was when Chung learned what had happened.

“My sister and I were tortured like that because one of the villagers told a lie about us and claimed we’d hidden our brother and were bringing him food,” Chung said. Chung asked the soldiers for a chance to face the villager who had told the lie about her. After Chung refused to reveal her brother’s whereabouts despite her awful torture, the soldiers brought the villager to the straw-thatched house. Running up to him, Chung wailed about how much she missed her brother and begged the villager to tell her where he was.

Realizing that Chung wasn’t lying, the soldiers beat the villager and demanded he tell the truth, at which the point he changed his story and said he must have seen someone else. Not long after this, Chung and her sister were released and allowed to return home, but the soldiers from the Northwest Youth League continued to disparage the girls as being rebels and monitored their activities.

A few days later, on Dec. 16, 1948, the Northwest Youth League took all the members of the town, including Chung, her sister and her mother, to Maemoru Hill to the west of the school. Just then, a soldier approached them and said, “This is going too far – these kids are innocent!” The soldier took Chung and her sister by the hand and led them away. That was how they survived their brush with death.

Torture trauma leads Chung to quit her job as a haenyeo diver

That turned out to be the last day Chung would ever see her mother, who was 54 years old at the time, the mother that Chung had missed so much while she was being confined and tortured. “They lined the people up and said they were the family members of rebels. Then they forced us to watch as they shot them all. Our mother was killed before our very eyes,” Chung said. Maemoru Hill, which is barely 50 meters away from Chung’s house, is now overrun with grass.

Chung’s sister suffered a great deal of pain as well. “Since my sister was three years older than me, she was tortured even more harshly than I was. They took her somewhere else out of fear we would try to line up our stories. Whenever I brought up that time late on, my sister couldn’t say anything out of fear that she would be detained again,” Chung recalled. After a long time passed, Chung’s sister told her that she had suffered “all kinds of things,” but she wouldn’t go into any greater detail.

Afterward, Chung lived a life of privation. Determined not to be disrespected by other people, she got married at the age of twenty to a neighborhood boy who had just been discharged from the army, and the two lived by the sweat of their brows. The haenyeo diving skills Chung had learned at the age of 17 helped her to build a house of her own in later years. She tried her hand at all kinds of jobs – diving for sea creatures and carrying them to the market to sell, along with vegetables and eggs. But she wasn’t able to keep up the diving for long because of the lingering effects of the torture she’d suffered. Whenever she got into the water, her whole body would ache, and when she came out again she would suffer awful spasms. Because of poor vision, she had two surgeries on her right eye and one on her left eye.

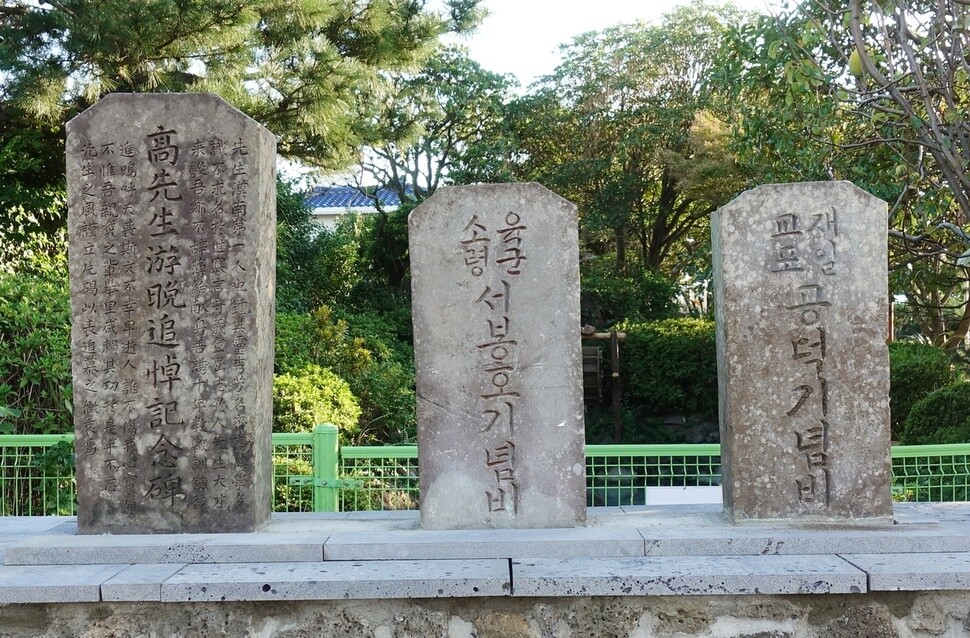

There are three memorial stones at the entrance to Gangjeong Elementary School. One dedicated to Seo Bong-ho, a major in the army, was erected by villagers in Feb. 1964. The stone says that Seo assisted the construction of the school in 1948. The following account appears in Hometown Stories at School, which was published by the Jeju Provincial Office of Education in 2014: “Second Lieutenant Seo Byong-ho had been dispatched to Jungmun to command the Jeju branch of the martial law command. When he became aware [of the challenge of building new classrooms], he had soldiers under his command guard villagers as they chopped down trees on Mt. Halla.”

But during the winter of that year, many residents of Gangjeong Village were killed by soldiers. A local history of the village published in 1996 mentions no fewer than 94 of these victims by name, and 59 people were killed in mass executions at Maemoru Hill and two other locations. The actual number of victims was presumably much higher than that.

“When I lie down at night, I think of those men”

On May 26, Chung was given the Jeju Apr. 3 Parents’ Award by the Jeju April 3 Peace Foundation. But the government never acknowledged that Chung suffered a disability during the Apr. 3 Uprising. She visited a doctor to get a diagnosis proving the disability, but the doctor refused, telling her there was no way she could receive official recognition for injuries suffered 70 years ago.

“When I lie down at night, I’m still reminded of the things I endured for nearly a month when I was young. When I close my eyes, I think of the cats and rats scurrying around, and I think of those men. Even now, when a cat sneaks into my yard, it frightens me so badly I throw water at it. I don’t leave food outside, either, since cats might come around.”

By Huh Ho-joon, Jeju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 3After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 4[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 5US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 6Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 7All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 8[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 975% of younger S. Koreans want to leave country

- 10[Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism