hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

A tale of survival and pain following the Apr. 3 Jeju Massacre

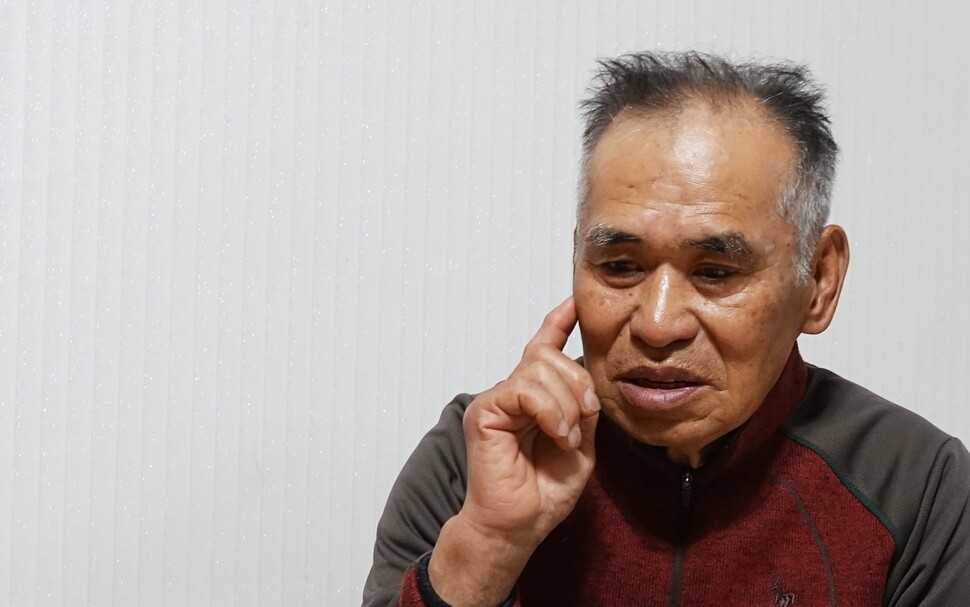

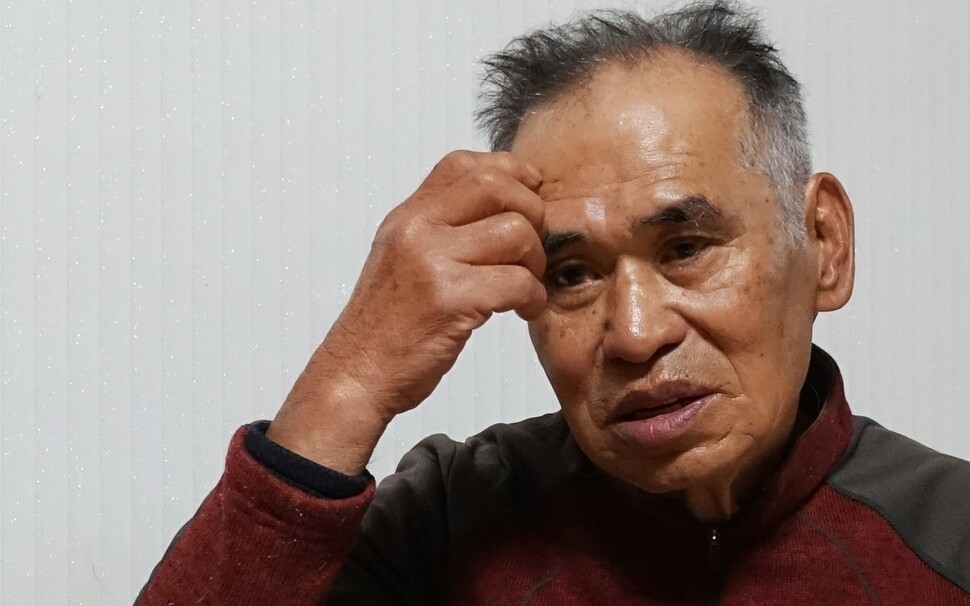

It was around 7 am on Nov. 15, 1948, shortly before sunrise. Jeong Hong-gi (76 years old, a resident of the Donam neighborhood) was at the house of his grandfather, Jeong Song-don, about 10m away from his home. Jeong’s family lived in the hamlet of Anjwa in Gashi Village, Pyoseon Township, South Jeju County (today called Seogwipo). While Jeong’s grandfather was helping him get dressed, they heard gunshots in the distance.

“Hurry up and get your clothes on,” Jeong’s grandfather urged him. “We need to get over to your mother’s house and get something to eat.”

A short time later, seven soldiers in helmets strode into the yard. This was just five days after Jeong’s mother, Kim Yeon-u (then 23), had given birth to a boy. In the kitchen, Jeong’s grandmother, Oh Gi-gyeong, was tearing off strips of buckwheat dough and putting them into a pot of sujebi soup for her daughter-in-law. The armed soldiers tossed blazing torches onto the straw-thatched roof and demanded that the family come outside. In the yard, the soldiers kicked around a bamboo basket that Jeong’s mother had been using.

Eight members of the family stood there trembling in the yard: Jeong’s grandparents; his mother, cradling her baby, just five days old; an aunt who was there visiting; the aunt’s daughter; six-year-old Jeong; and his three-year-old younger brother, Jeong Hong-taek (73 today). All at once, the soldiers opened fire, killing everyone in the family except for Jeong and his younger brother. When his mother was shot, the newborn she was holding fell from her hands. Jeong saw dark blood spurting from the baby’s ears.

“I think they only shot the adults and spared me and my little brother because we were so young. I still remember everything that happened that day so vividly,” Jeong said.

As the straw on the roof burned, a thick cloud of smoke and an acrid odor filled the streets. Anjwa was a remote hamlet on the slope of Mt. Halla, a little over 2km from where most of the people in Gashi Village lived.

Slaughter and burning houses “reminiscent of the horrors of hell”

The situation on that day is explained as follows in Gaseureumji, a local history published in 1988 by Gashi Village: “A major operation to wipe out the communist guerillas was carried out in Gashi Village. Gunfire began early that morning, and flames began shooting up all over the place. There were awful scenes where some of the residents who had not fled were slaughtered by the soldiers or burned to death. The gunfire stopped in the afternoon, but the roaring flames and billowing smoke blanketed the sky, and the pathetic sound of weeping filled the whole village. It was reminiscent of the horrors of hell.”

Gashi Village, where the main business was raising livestock, was one of the villages that suffered the most during the Jeju Uprising, which began on Apr. 3, 1948. Once again, Gaseureumji has the details: “374 people were killed; 12 people went missing; 363 houses were burned down; and some 1,200 people were made refugees. The number of livestock lost amounted to around 1,000 cows, 600 horses, 370 pigs and 2,000 chickens.”

On this day alone, more than 30 people lost their lives. About 160 of the villagers were held at Pyoseon Elementary School, and on Dec. 22 of that year, the soldiers killed 76 of them at Beodeul Pond, in Pyoseon Village. If even one family member was unaccounted for, that person was assumed to be a fugitive and the rest of the family were executed by firing squad.

After the soldiers left the blood-spattered yard, Jeong’s grandfather staggered to his feet. Though blood was dripping from his left arm, he grabbed his two grandsons and took them to shelter in a nearby bamboo grove. When the soldiers who’d been standing next to the stone wall couldn’t be seen any more through the bamboo trees, the three of them went back home. The dead bodies of Jeong’s grandmother, mother, infant brother, aunt and aunt’s daughter were sprawled around the yard.

“My grandfather looked really cold, probably from losing so much blood. He stamped out a smoldering straw mat, wrapped himself in it and took a nap,” Jeong said.

“The neighbors that had taken flight survived, but we couldn’t flee because of the newborn. We were all together, and they just mowed us down. My father [Jeong Yeong-ik, 22 at the time] fortunately managed to take shelter when he heard the gunfire, which saved his life.”

Amid such tragedies, the sunshine was warm all day long. As the sun shone down, Jeong’s grandfather and the two boys sat down beneath a camellia tree behind the ashes of the house. Jeong’s grandfather cracked open an egg and poured it out onto his bleeding arm. Next, he used a hand hoe to chop branches off a willow tree and bound his arm with them. Around sunset, Jeong’s father came back. As soon as he stepped into the yard, he began wailing in a loud voice, but he couldn’t work up the courage to lay the bodies to rest. Relatives who had taken flight came back after dark.

“My great uncle’s house in the village hadn’t burned down, so we all gathered there. Since I’d stayed in hiding since that morning without eating anything, I was hungry. I remember that for supper we ate one of my grandfather’s pigs that had died in the fire,” Jeong said.

The family spread dirt over the bodies of those killed in the yard as a makeshift burial. In the middle of the night, the survivors left the hamlet and relocated to the home of Jeong’s maternal grandparents, in Sinheung Second Village, Namwon Township, just over 6km away.

That night happened to be the October full moon, by the lunar calendar, and the moon lit up the forest around them. “My aunt carried me and my father carried my three-year-old younger brother as we walked along the forest path to my aunt’s house, in Sinheung Second Village. My grandfather, whose arm was hurt badly by the bullet, went with us. The moon was shining brightly, and no one said a word as we walked along.”

Jeong’s father made two trips from Sinheung Second Village back to their home at Anjwa to bury the bodies of the dead family members. When he was about to make his second trip to Anjwa, Jeong tried to stop him from going. “I chased after him and begged him not to go. That was the last time I saw my father’s face,” Jeong said.

The last night Jeong saw his father

While Jeong’s father was making his way through the woods, he ran into a guerilla band who forced him to join them. Jeong didn’t learn what happened to his father until long afterward. At some point, his father presumably either surrendered to or was apprehended by the government troops. A list of people incarcerated by a military tribunal shows that Jeong’s father was sentenced to 15 years in prison on July 2, 1949. He was sent a prison in Daegu to serve his sentence and was transferred to a Busan prison on Jan. 20, 1950. After that, nothing more was heard of him.

The name of Jeong’s missing father is inscribed on a grave for the missing at the Jeju Apr. 3 Peace Park, located in the Bonggae neighborhood of Jeju City. Jeong’s paternal grandfather stayed with Jeong at the home of his maternal relatives until June 25 of the next year (May 29 on the lunar calendar), when he died of complications from his gunshot wound.

Even after reaching Sinheung Second Village, Jeong had to move around several times as a consequence of the Apr. 3 Uprising. After three years of that lifestyle, nine-year-old Jeong was brought back to Gashi Village. Jeong, as it happened, was the family’s 11th-generation jongson, the eldest living male who had a duty to carry on the family line.

“My relatives had a family meeting and decided that my brother and I shouldn’t both be left with our maternal relatives. Since I was the jongson, they brought me back to Gashi Village to live at my great uncle’s house, while my younger brother stayed with my maternal relatives,” Jeong explained.

The duties of the jongson and the harsh realities of life without education

After returning to Gashi Village, Jeong lived in a walled encampment there. In order to prevent guerilla raids, the army and the police enlisted the residents of Pyoseon Township to build a stone wall around the village. The villagers had to build a smaller wall inside the larger one and live in communal huts covered with silver grass. It wasn’t until Mar. 1955 that the villagers were allowed to return to the places where their homes had been. Jeong had come home, but his family couldn’t afford to send him to school. Jeong envied the kids his age who went to school and felt bitter about his lot in life.

“From the age of 15, I would go to the woods to bring back kindling in the winter, and I also had to feed the cows. That was when I started going to the woods to make charcoal. While my friends were going to middle school, I was out making charcoal, making string out of silver grass and carrying the charcoal on my back all the way to Pyoseon Village to sell. During the summer, I spent all my time working in the fields,” Jeong said.

Pyoseon Village was a full 10km away from his home.

At this point, Jeong’s wife, Kim Yeong-ja (77), who was sitting beside him, broke in.

“If my husband’s paternal family hadn’t made him work like a dog doing the rituals as the eldest son, he could’ve lived with his maternal family. Since he didn’t have a chance to get any education, life has been so hard for us. Even a little education would’ve taught him to read. That’s the thing I resent the most. I don’t even know how we made ends meet.”

When Jeong was 20 years old, he met Kim, who was 21 at the time, and fixed up the old house in Anjwa for them to live in. Kim went on: “Since Jong is the jongson, there are so many ancestral memorial rites to prepare. There are three rites in the first month of the lunar calendar, including the New Year, and there are three more in the eighth month, including Chuseok, along with various other rites to prepare in the other months. We did all of them.”

Jeong has been a supporter of the Democratic Party his entire life. That’s not because of his political philosophy, though. It’s simply because he thought the Democratic Party would work to resolve the issue of the Apr. 3 Massacre of so many innocent people. When there was talk of shutting down the Apr. 3 Commission during the presidency of Lee Myung-bak, Jeong was outraged. “I couldn’t believe that people were capable of that,” he said.

“Even if the government tackles the Apr. 3 issue, it won’t bring complete relief to the spirits of the departed, but they should still get reparations, even if it’s just one out of a hundred. Innocent people were killed, so reparations should be paid,” Jeong said.

“On Apr. 3, I get excited at the thought of going to the Peace Park. I never saw my father-in-law’s face, but visiting the park sets my heart at ease,” said Kim, Jeong’s wife.

“It’s the same for me,” Jeong said. “Even now, I still think of my parents a lot.”

By Huh Ho-joon, Jeju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 4Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 5Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 6Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 9[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 10Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report