hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

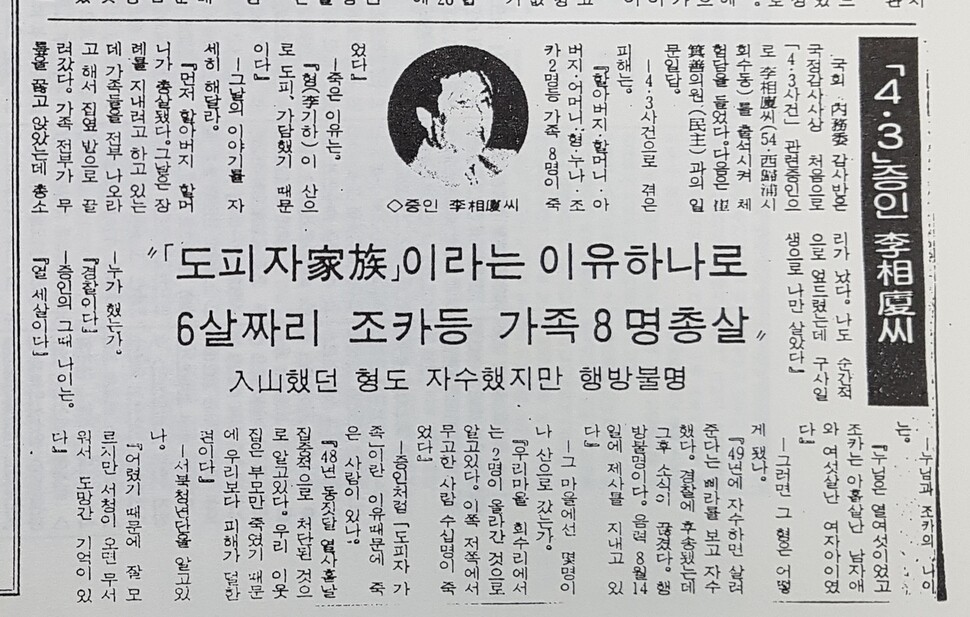

“Families” of fugitives executed by police officers during Jeju Massacre

“Who shot them?”

“A policeman from the Jungmun police branch.”

“Are you telling me it was a police officer who shot your family?”

“Yes.”

It was 5 am on Sept. 24, 1989, and a Jeju resident was answering questions from a lawmaker while appearing as a witness at the 13th National Assembly Home Affairs Committee’s parliamentary audit of Jeju Provincial Office. The second question suggested the lawmaker was unwilling to believe the resident when he said that a police officer had been the one who shot his family members.

The witness that day was Lee Sang-ha, now an 84-year-old resident of the Jungmun neighborhood in Seogwipo. According to the parliamentary audit records, Lee had had to wait for 14 hours after the audit began on Sept. 23, only appearing as a witness at around five the following morning. After waiting so long to take the stand for a mere 20 minutes, Lee proceeded to relate the fate of his family during the events of the Jeju Uprising (known locally as Jeju April 3), despite having been told by a National Assembly member that day to stick to what he had promised to say beforehand.

“I’m going to state the facts,” Lee declared.

It was the first time a victim of Jeju April 3 had broken the “taboo” of speaking out about their experience during a parliamentary audit. The same reporter who covered the events that day caught up with Lee 30 years later on Jan. 6. Recalling the experience, a smiling Lee said, “I spoke the truth, yet one of the National Assembly members didn’t believe me. He just couldn’t believe what I said. He had an expression on his face like, ‘How could that have happened?’”

Family was preparing for a funeral for grandparents

At around 8 am on Dec. 17, 1948, around 20 to 30 relatives, relatives, and other pallbearers were gathered at Lee’s home next to the Hoesu Village shrine in Jungmun township. They had finished breakfast and were preparing to head to his grandparents’ burial site. It was a funeral for grandfather Lee Won-ok, 71, and grandmother Kang Ju-hyang, 64, who had been killed by police three days earlier. Believers in the local indigenous faith, they had been operating a local private school for nearby residents at the location of today’s Jungmun High School, around 1.5km from the village, when they were slain that Dec. 15.

As Lee’s family busily prepared for the funeral, the house was set upon by a police officer from the Jungmun police branch and a group of three to four young students holding bamboo spears. “Come on out,” the policeman said to Lee’s father Lee Du-hyeon, 48, and mother Kang Tae-sa, 46. The father stepped outside, instructing the other family members in the house to come with him. Six of them joined him, including then 13-year-old Lee Sang-ha; his sister Hwa-seon, 16; and Lee Gil-pal and Lee Chun-ju, the seven-year-old son and six-year-old daughter of his brother Gi-ha, 25. As the family members and neighbors assembled, a sudden feeling of tension descended over the same yard where they had just earlier been busily preparing for the funeral.

“He didn’t have to bring me, my sister, or his niece and nephew, but my father was a real straight arrow, and he insisted that we all come out,” Lee Sang-ha recalled.

“My father had been called to the police branch a few times before, and they’d let him go. I think he thought it would be all right.” As Lee’s family went out onto the walkway, the policeman herded them toward a field. The friends and relatives at the house were instructed to watch.

Although it was a winter day, the weather was clear and it did not feel cold. Lee’s family members walked down the front hill to the field. Residents of the mid-slope village of Hoesu were mostly dry-field farmers; Lee’s family farmed sweet potatoes, millet and buckwheat. The policeman told them to turn and sit down. Perhaps predicting his fate, the father and grandmother stooped forward, respectively clutching their grandson and granddaughter. Lee Sang-ha – then a fifth-grader at Jungmun Elementary School – and his sister sat down with them.

Bullet misses Lee’s neck and he survives

The relatives and neighbors watched anxiously as the moment of execution came. The father told the policeman he was going to sing “Long Live the Republic of Korea”; perhaps he thought he might be spared, Lee said. But as the sounds of “Long Live the Republic of Korea” rang out, a pistol was fired from behind him, and he fell. Lee instinctively flattened himself against the ground.

“When I was attending elementary school during the Japanese occupation, we did a lot of practice where they would yell ‘air raid’ and ring a bell, and we would run and dive down,” he remembered. “I must have flung my body down like that automatically.”

Standing by the roadside, the policeman fired at the family members in the field. He then approached their bodies and fired additional shots into each one to make sure they were dead. The bullet aimed at Lee’s head just missed his neck. It struck the ground, and a piece of dirt flew up into his mouth.

“When they shoot you, you don’t die right away, so he came over to make sure we were dead. Fortunately, I wasn’t hit,” he said.

“The dirt had flown up in my mouth when the bullet hit the ground, so I just remained there without being able to speak, and that’s how I survived.”

His brother’s son, whom the grandfather had been holding, was hit in the thigh but did not die at the scene. That [police officer] may have been scared, because he heard my nephew crying and just left. A man who had worked for the local private school was a clever man. He wrapped me in a blanket and took me to my relatives’ house. He also took my nephew, but he cried all night long before eventually passing away.”

After the loss of his grandmother and grandfather, Lee had now seen his father, mother, six-year-old sister, seven-year-old nephew, and six-year-old niece killed. The Lees had been killed because he was part of the family of a “fugitive” – his brother, who had fled into the mountains after the Jeju Uprising. Dozens of people from “fugitive families” were massacred by punitive forces that day, at shrine sites in the Jungmun township villages of Hoesu and Jungmun. The forces had murdered the people at Lee’s home simply because they were the family members of a fugitive.

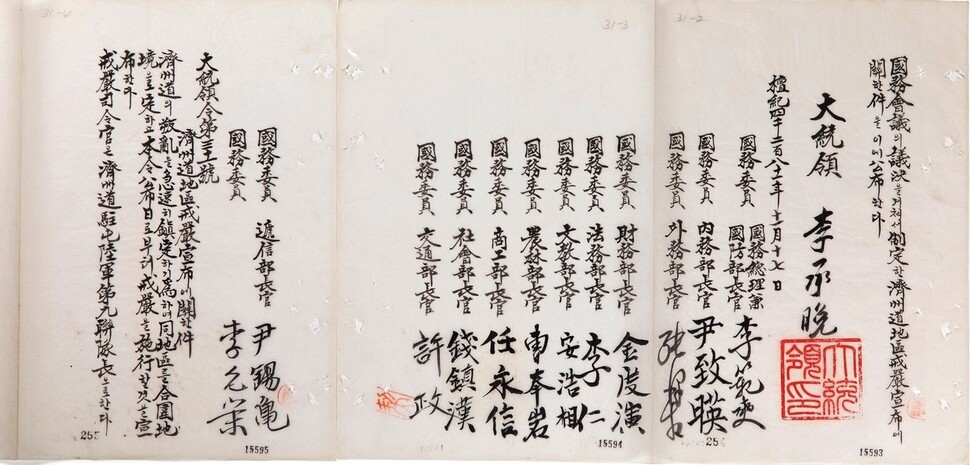

Martial law gave soldiers free pass for slaughter

On Oct. 17, 1948, the 9th regiment designated the inland region beyond 5km from the coast as

“Red territory” in their suppression campaign on Jeju Island. When martial law was declared across the island on Nov. 17, it descended into a bloodbath. After a Nov. 5 attack by guerrillas on the Jungmun township office and police branch, a special squadron from the 9th Regiment – made up of young defectors from North Korea – was stationed at Jungmun Elementary School. Additional reinforcements from other regions were posted at the police branch alongside the native Jeju police.

Lee’s family was called to the branch after the guerrilla attacks, but he and his sister returned the same day, and his father and mother the next. This was why the father had believed nothing serious would happen – yet he ended up falling victim to a massacre. Soldiers from the 9th Regiment stopped in the village of Hoesu while marching from Seogwipo to Jungmun village after the police branch was attacked. They hurled a grenade at the outer house where the brother lived, claiming that they heard somewhere that it was a “fugitive’s home.” Millet from the fall harvest was piled on the floor; straw fell onto the grenade, preventing the fire from spreading. The next day, the father – fearful of a misunderstanding – set fire to the outhouse himself.

“I guess he thought they might let him live if he did that,” Lee recalled.

Drafted during the colonial occupation after graduating from elementary school, Lee’s brother was “the best student even as a young man,” he recalled. During the colonial period, the strapping youngster was renowned in the neighborhood for his running and wrestling prowess during the village’s intervarsity athletic contests. After fleeing into the hills in 1948, he came down to Hoesu village in March 1949 after seeing a leaflet promising he would be spared if he surrendered. “Look after my younger brother,” he reportedly told a Hoesu resident before proceeding to the Seogwipo Police Station. He was never seen again after that; rumors circulated that August that he had been executed at the Jeju airfield.

Taking Lee in after his miraculous survival of his entire family’s massacre, his relatives felt anxious. After about 10 days had passed, they had a friend tell an army second lieutenant responsible for the police branch that one of the children had survived. “What should we do?” they asked him. The second lieutenant said to bring Lee to him.

“I went to the station on my own. When I got there, the second lieutenant said, ‘The heavens have spared this child. Now our military is going to take him.’ Hearing that, the relatives pleaded with him. ‘If you just give us permission, we can look after him,’ they said. And that’s how I ended up living with my relatives.”

Tears welled up in Lee’s eyes as he recalled the memory. He lived with his relatives for some time before relocating to his old house with their mother. His older sister, then 22, had married before Jeju April 3. When her husband was drafted after the Korean War’s outbreak, she also came to live at the house for two years.

It was during this time that they began holding rites to honor their family members. “First, it was my sister who did the rites,” Lee remembered.

“She would put three meals on the table each day – once they were all placed, it was like a major holiday. We had to eat all that food, so I couldn’t eat warm rice.”

Life after being orphaned

Even after being orphaned, Lee attended middle school. Graduating from a commercial high school in Jeju City, he proceeded to university. After attending for one semester around 1957, he had no money to pay tuition for the second. Traveling as a stowaway, he attempted to visit relatives in Tokyo. He was caught on an island in Nagasaki Prefecture and spent eight months at Sasebo Prison and 16 months at Omura Detention Center before returning to Jeju. He spent three years in the military, relocating to Jungmun near his home village of Hoesu after his discharge in 1962. In 1970, he studied mandarin orange farming for a year while living in Tokyo; he went on to become a pioneer in cultivating the crop. He also studied pig farming.

With his experience witnessing and living through his family’s execution as a young child, Jeju April 3 is a traumatic memory for Lee.

“When you’re by yourself, you have all sorts of crazy thoughts. My mind wandered every day and I couldn’t concentrate, so I wasn’t good at my studies. In elementary school, I was good at the abacus and calculations, but after Jeju April 3 I lost my sense for numbers. It’s like the way an earthworm keeps wriggling when it’s cut in half – a person who’s been shot will keep wheezing. I saw it with my own eyes.”

Compensation is necessary

During the 1989 parliamentary audit, one of the lawmakers asked Lee, “Don’t you feel any bitterness toward society?”

In reply, he said, “I live my life seeing my fate as someone born in those times. So I’ve never had any hard feelings or anything toward the state.”

His views on that remain unchanged.

“If I thought about April 3, I couldn’t live. I live because it’s my fate,” he said.

But he also insisted that compensation was necessary.

“We can’t rehabilitate our reputations without compensation. You give compensation when there’s a traffic accident – you can’t just have an apology from the president when people have been killed. However much it is, there needs to be compensation.”

By Huh Ho-joon, Jeju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 4Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 5US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 6[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 7All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 8[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 9Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 10More South Koreans, particularly the young, are leaving their religions