hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Several Jeju Massacre victims refused disability status

According to a South Korean law that was instituted to investigate the 1948 Jeju Uprising and to restore the reputations of its victims, people who suffered a disability during the massacre are counted among the victims. The Jeju residents who were injured by the armed rebels or the government troops and left with a disability are regarded as having a “Jeju Massacre disability.” But some of them have been refused official recognition of their disability without any clear reason, while others aren’t even aware that they have the option to apply for disability status.

Jang Yun-su of Bukchon Village was shot by the police

Around 11 am on Aug. 13, 1947, 18-year-old Jang Yun-su (now 90) was weeding a millet field on Seou Peak, in Hamdeok Village, Jocheon Township. It was a muggy morning, and she decided to go diving. Her plan was to go home for some lunch and then take her nets and other diving gear to the sea near Bukchon Village. But when she’d nearly gotten home, she saw her neighbors running and she followed them, with her hoe still in her hand. In a little while, a gunshot ran out, and Jang collapsed on the spot.

“I’d gone out to the field by myself, and I was on my way to go diving at high tide when it all happened. I’d been planning to have lunch at home and go to the beach. But then I saw people running in front of me, and they told me to stop working and watch what was happening. So I was on my way back from the fields when I ran after them. I’m a pretty fast runner. I remember everything until I got to Neobeunsungi and got shot, but nothing after that,” Jang said.

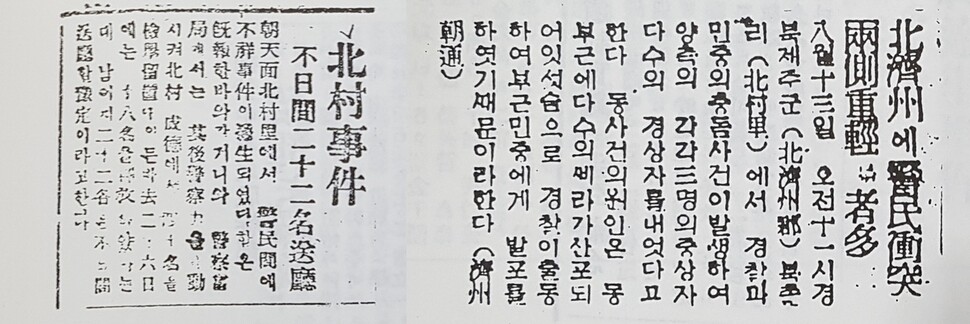

Jang’s younger brother Yun-seung, 87, was 15 years old at the time, in the fifth grade at Bukchon Elementary School. Jang Yun-seung describes the situation at the time as follows: “Leading up to Liberation Day [on Aug. 15], some youngsters had been putting up fliers commemorating Liberation Day on the stone wall of our house. Cops from the Hamdeok police station, which was nearby, were asking any young people they ran into about the posters, which led to a scuffle between young people and the cops. An undertaker in the village turned on a siren and told everyone to gather around because the cops were beating some youngsters from Bukchon. My sister was running in that direction when she was hit by a bullet. Three people were shot altogether, including a friend of my dad’s and another woman.” Jang was shot even though she didn’t have anything to do with the fliers. The shootings on that day were even reported in the newspaper around that time.

No recognition for a Jeju Massacre disability

The bullet fired by the police passed below Jang’s right collarbone. Her chest was drenched with blood, and all her neighbors thought she was dying. After hearing that his daughter had been shot, Jang’s father (Jang Gi-ryong, 55 at the time) and her younger brother loaded her in a passing truck and set out for a general hospital in the town of Jeju.

Incensed at his daughter’s gunshot wound, Jang’s father had the truck stop at the Hamdeok police station, where he told the police that his daughter had been fatally shot and that they had to save her. Jang destroyed some equipment at the station and ripped rope off the station’s straw roof. But instead of apologizing or offering any compensation, the police charged Jang’s father with property damage. Jang’s trial was held on Sept. 26 of the same year, and he was convicted of sedition and other charges and sentenced to six months in prison, suspended for three years.

A doctor told Jang’s father that his daughter would have died if she’d been hit on the left side but that she survived because she’d been hit on the right side. The other two people who’d been wounded by gunfire were released from the hospital fairly soon, but Jang was so close to death that she ended up staying in the hospital for three months. Even after being discharged, Jang remained bedridden for quite some time.

“My wounds got better and didn’t hurt when I went diving in my early years, but later on the aftereffects of my wound began to appear,” Jang said. She pointed to her wound and when she pressed the area below her collarbone, the skin gave beneath her finger.

“When it gets cold, my right arm gets so weak I can’t use it. When my arm gets wet, the area around the bullet wound freezes up. When it gets cold or even just windy, I get so sick I can’t move,” Jang said.

Last year Jang’s her application passed a review after being refused twiceDespite the gunshot wound and the testimony of the other villagers, Jang has twice been refused recognition for a Jeju Uprising disability, once in 2004 and once again in 2014. “I don’t understand why they won’t recognize my disability,” Jang said.

“When I visit a doctor, they say I don’t have any wounds even though they can see where the bullet entered and left my body. I think it’s pretty weird they say I don’t have any wounds when they know I was hit by a bullet. The older I get, the worse the aftereffects seem to get.”

At the end of last year, Jang applied again to receive recognition for having a Jeju Uprising disability, and this time her application passed a review by the Jeju Uprising Working Committee, the first step in the process. “When Yun-su applied for disability status before, she didn’t get it. That’s pretty ridiculous considering that she’s been suffering from that bullet wound all her life,” said Jang Yun-seung, Yun-su’s younger brother.

“Since I never had the chance to talk to my mom or dad, the words just wouldn’t come out. I was so jealous to hear my friends talk about their mom and dad,” said 74-year-old Kim Jeong-ah on Jan. 13. During the Hankyoreh’s phone interview with Kim, who lives in Nippori in Tokyo’s Arakawa Ward, her voice made it obvious that she was crying. Kim is from Gonae Village in Aewol Township, North Jeju County (today part of Jeju City), but she has been living in Japan for nearly 40 years now.

Kim grew up hearing what had happened on that day from her grandmother, Kang Shin-haeng. On the evening of Nov. 13, 1948, a meeting was held at the village hall about how to deal with “those people.” One of the people at the meeting was Kim’s father Kim Bong-won, 24 years old at the time, who said that the villagers shouldn’t listen to “those people.” Kim used the expression “those people” in place of “the rebels.”

“’Those people’ had been eavesdropping at the meeting. They waited until the meeting was over and we’d gone to bed, and around 2 o’clock in the morning they came into our house and attacked my mom, my dad and even me, a toddler, with their knives and bamboo spears,” Kim said.

While many residents of Jeju Island were killed by government forces during the Jeju Uprising, there were also some civilians who were killed by the armed bands of rebels. The rebels showed their vicious side when they slaughtered people who weren’t cooperative or whom they believed to be on the side of the government troops.

The parents died, but the wounded baby survived

“My dad died on the spot, and my mom lingered on for ten days despite being severely injured and in great pain, as if she didn’t want to leave her little baby alone. Everyone assumed I would die and my mom would live, but the opposite happened,” Kim said. Her mother, Oh Chang-sun, was 23 years old at the time. The rebels even turned their bamboo spears on Kim, who had just turned two, inflicting grievous wounds on her arms, chest and right ear.

Kim’s father was an intellectual who had graduated from a university in Tokyo during the Japanese colonial occupation. After liberation, he’d helped set up Aewol Middle School and taught math until his death. “After the school was established, people encouraged my dad to go to Japan, but he settled in that village because he wanted to be a teacher,” Kim said.

“My grandma would often weep in front of my dad’s grave. She paid many visits to his tomb. I can’t forget how my grandmother would just wail, without saying a word, in front of that grave.”

Kim’s grandmother, who passed away 30 years ago, never showed up at Kim’s school for an entrance ceremony, graduation ceremony or sporting event. Kang felt sorry for her granddaughter, but she said she couldn’t bear going because it reminded her of her son and his untimely death. Determined that her other children would be spared, Kang put her surviving younger son and daughter (Kim’s aunt and uncle) on a blockade runner and smuggled them into Japan.

Oozing ears and a shattered body

Kim has no recollection of the Jeju Uprising, even though it left an impact on her body that’s still evident seven decades later. Although Kim survived her brush with death as a toddler, her injuries still affect her. “My grandma wanted to save her son’s only child, so she acted as a diligent nurse. Over time, the wounds on my chest, shoulders and arms healed, but my ear didn’t get better,” she said.

Kim’s body is still scarred from the injuries she suffered that day. “When I wear short-sleeve shirts in the summer, people gawk at my arms and ask what happened to them. They’ve gotten a lot better since I was injured as a child and I’ve even had reconstructive surgery, but the scars still remain.”

But Kim can’t hear anything out of her right ear, which has oozed pus since she was a child. “I got so embarrassed about my ear oozing without my knowledge when I was around other people that I started covering it up with a handkerchief,” she said.

After Kim got married, she had an operation at a large hospital in Seoul. The doctor warned her that her hearing was unlikely to be restored, but she was so desperate that she got it done anyway. After moving to Japan, she visited a major hospital in Tokyo, where she was once again told there wasn’t any treatment that could cure her.

Kim visited Jeju Island in Oct. 2018. She’d heard that the Jeju April 3 Peace Park had been built and that the government was creating a registry of the victims of the Jeju Uprising and their bereaved family members. With the help of the Jeju April 3 Peace Foundation, she applied for Jeju Massacre disability status.

“I hadn’t even told my daughters because I didn’t want them to feel sorry for me, but now I’ve told them about what I suffered in the Jeju Uprising. The Jeju Uprising still brings pain to my heart,” Kim said in a voice that was drenched with tears.

Decision on disability status awaits a committee review, still unscheduled

An individual who is recognized as having a Jeju Uprising disability receives coverage for their medical expenses and a stipend of 700,000 won (US$626.79) a month from the local government. But getting that recognition is quite complicated. Currently, only 75 people are recognized as having a Jeju Uprising disability. The last time a decision was made about Jeju Uprising disability status was in May 2014. Among 33 applicants, only 7 were recognized, while the other 26 were rejected. As part of an application for disability status, an individual must submit a medical certificate and proof of the incident. The application must then pass a preliminary review by the Jeju Uprising Working Committee and a final review by the Jeju Central Committee, under the Office of the Prime Minister. At the end of last year, 34 applicants for disability status passed a review by the Jeju Uprising Working Committee. Thus far, the next meeting of the Jeju Central Committee, which is chaired by the Prime Minister, has yet to be scheduled. The applicants are all elderly individuals, most of them over 80 years old.

By Huh Ho-joon, Jeju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8917132552387962.jpg) [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces![[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8317132536568958.jpg) [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

- [Guest essay] At only 26, I’ve seen 4 wars in my home of Gaza

- [Column] Syngman Rhee’s bloody legacy in Jeju

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 2Faith in the power of memory: Why these teens carry yellow ribbons for Sewol

- 3[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- 4[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- 5Korea ranks among 10 countries going backward on coal power, report shows

- 6Final search of Sewol hull complete, with 5 victims still missing

- 7[News analysis] Watershed augmentation of US-Japan alliance to put Korea’s diplomacy to the test

- 8How Samsung’s promises of cutting-edge tech won US semiconductor grants on par with TSMC

- 9K-pop a major contributor to boom in physical album sales worldwide, says IFPI analyst

- 10World famous Korean instant noodle: truth and misconceptions