hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Orphaned and enslaved during the chaos of the Jeju Massacre

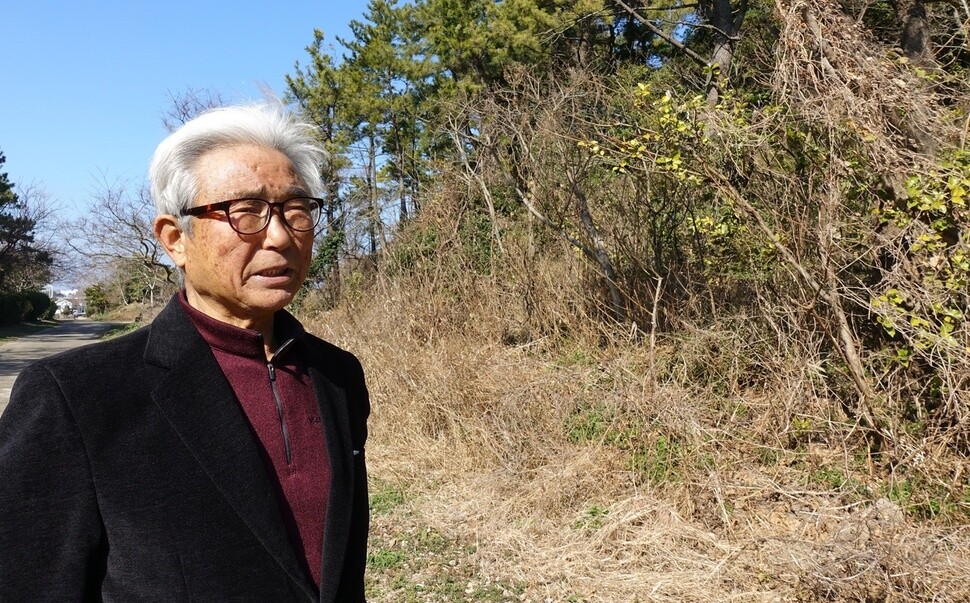

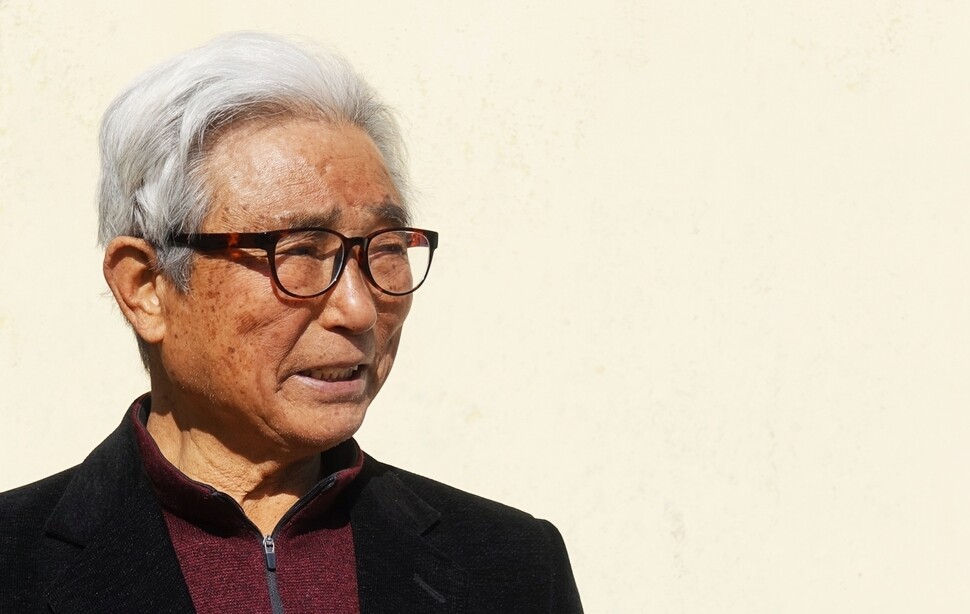

The pines and other trees of Yeondumang Hill stood lush across from the Jeju Haenyeo Museum in Jeju City’s Hado village on the morning of Jan. 18. A marker off to one side indicates that the 21st Jeju Olle course passes by here. Oh Su-song, 87, appeared conflicted. Standing next to a narrow path leading into the hill, he pointed toward a place where the forest was especially thick.

“It was here. This is where my mother and father, little sister, and little brother were all killed in one day after we were held at the Sehwa police branch internment camp.”

Those traveling from Hado to the village of Sehwa must pass by Yeondumang Hill. Located at the junction of Sehwa, Sangdo, and Hado, it is the setting where local haenyeo (women divers) gathered in Jan. 1932 for a demonstration against the plundering practices of the occupying Japanese. In front of it stands a memorial to the Jeju haenyeo’s (female divers) movement against the Japanese and busts of three independence activists – Bu Choon-hwa, Kim Ok-ryeon, and Bu Deok-ryang – who led the divers’ campaign.

Oh’s voice took on a tremulous note as he pointed to the forest.

“When I was a boy, this was a big hill. There wasn’t any scrub or forest like there is now, and the area around it was just sandy beach,” he said. The same place that had marked the beginning of the haenyeo’s campaign – a female-led movement against the Japanese occupation – became a setting for slaughter during the events of the Jeju Massacre, known colloquially as Jeju April 3. Oh remembered the events of “that day” as clearly as if it had happened the day before yesterday.

At around 10 am on Feb. 10, 1949, a police officer from the Sewha police branch in Gujwa Township (now part of Jeju City) ordered residents interned at the camp across the street to “come out.” Forty or so residents were lined up by police in front of the branch and led to Yeondumang Hill in nearby Hado. Surrounding them were five to six police officers.

The road was muddy after heavy winter rains the day before; the cold enshrouded their bodies. Although Yeondumang Hill is only a little over a kilometer from the police branch site, it felt like a long march. The ones making the journey were local residents from the villages of Hado, Jongdal, and Sehwa. Oh, who was 17 years old at the time, was being marched along with her father Oh Do-won, then 52, and mother Ko Eul-saeng, 45. Once they arrived at the hill, the police instructed the residents to stand in rows. The moment of execution had arrived. Oh’s father pleaded with the police. “Please spare one of my children so they can pour a bowl of water before our ancestors,” he said. His mother cried out, “Please spare my son at least.”

Oh is spared while the rest of his family is executed

Oh had become a familiar face among the police during his time at the camp, performing various duties for the police branch including drawing water and running errands. With the parents’ desperate entreaties, and the fact that they knew his face, the police picked Oh out and instructed him to go to the police branch. He had walked about 150m when he heard the rattle of gunfire behind him. In all, around 40 people were killed on the spot. The massacred residents had been classified as “families of a fugitive,” with at least one family member who had gone into hiding.

“Not a single thought went through my head. I felt like my heart had stopped. For a few days, I couldn’t even eat. So many people had died in front of me, including my own mother and father. They killed not just elderly people but children, even newborn babies.”

The same police who had shot Oh’s parents brought him back to perform more errands for the police branch.

Oh’s younger sister Young-ja, 12, and brother Hong-rim, 8, had been back at home; Oh had thought his elder relative was looking after them. Two days after his mother and father were killed, his uncle, who ran a fertilizer distribution center in Sehwa, visited the house in Hado to pick them up – but they were not there.

After massacring Oh’s parents and the other residents, police had descended on Hado Village once more the same afternoon to capture more “families of fugitives.” His two young siblings had been taken to the same place. They had tearfully pleaded with the police to spare them, but the police opened fire anyway. Oh, who had been doing errands at the police branch at the time, heard the news from his uncle.

“A lot of residents witnessed the executions. Hearing what they said, I was so stunned I couldn’t speak. They said they couldn’t bear to look at the way my brother and sister were pleading for their lives. Can you imagine how I felt hearing that?”

Unable to give his family a proper burial

Collecting the bodies of his slain family members was out of the question.

“The people with relatives were all taken away, but I was out of my wits, and I couldn’t collect them on my own. My uncle covered my parents’ and siblings’ bodies with dirt as a marker, then went back and buried them in a field about five months later.”

His entire family branded as criminals due to brother’s activities

The reason the Ohs were branded a “fugitive family” was because of his brother, three years his senior. On Mar. 1, 1947, police opened fire shortly after a rally at held at Jeju North Elementary School to commemorate the March 1 Independence Movement. Six residents were killed, ranging from an elementary school student who was watching the street demonstration to a mother in her 20s and the infant she clutched to her chest. After that incident, police issued a sweeping arrest order for the region. Oh’s brother Jang-song, then 20, was apprehended by police from the Sehwa branch after taking part in a March 1 rally at Manse Hill in Jocheon. The police subjected him to various forms of torture, demanding to know “who was responsible” and what they had done.

“The police beat my brother to the brink of death with their clubs. His teeth were broken and he couldn’t move,” Oh remembered.

Released after around 20 days of internment at the branch, the brother feared he might be apprehended again if he remained at home. Instead, he hid himself in the fields and the house’s shed. As the events of Jeju Uprising intensified and the punitive forces’ campaign wore on, he took refuge in the hills, concealing himself in a small cave near the Darangswi oreum (a defunct volcano).

Before the scorched-earth campaign was launched in Oct. 1948, Oh’s father went to see his brother to send him off to the mainland. Licensed to operate powerboats during the Japanese occupation, the father had recruited sailors in his 30s to catch sardines in the waters off of Chongjin in Hamgyong Province (now part of North Korea) – but since arriving in his hometown in the wake of Korea’s liberation, he had operated a sailboat.

“He went to the mainland on that boat. The situation had started to deteriorate, so my father somehow went and found my brother to send him off to the mainland. The police gathered together all the boats in the Hado port and drilled holes in them so they couldn’t operate. It was to stop people from fleeing.”

While continuing to do errands at the police branch, Oh received word from an elementary school classmate of his brother’s who had accompanied his brother before defecting. “Your brother caught frostbite during the deep winter in the upper hills,” the classmate told him. “He wrapped his foot in clothing and continued in hiding until he starved to death around the end of March 1949.” But he was unable to collect his brother’s body; at the time, he was barred from going anywhere without police permission. The memorial stone for his brother at Jeju April 3rd Peace Park reads, “Whereabouts in Jeju area unknown after March 28, 1949.”

Tortured and detained with his parents

It was around the end of Oct. 1948 that Oh’s mother and father were taken to the Sehwa police branch as “members of a fugitive’s family.” First, they went to the Hado village hall. The residents taken to the village hall that day were then led to the police branch. At the branch, they were subjected first to vicious torture. Oh was taken to the branch around two weeks after his parents. He was tortured with electric shocks almost as soon as he arrived, as the police tried to force him to say where his brother had fled. Next, they would place wooden sticks in his fingers and step on them, or put a piece of wood between his thigh and calf, have him kneel down, and step on him from above.

“What answer could I give them? I didn’t have any word about my brother. When people didn’t produce answers, they would torture them to death in different ways. It wasn’t just me that it happened to – most of the people taken to the branch were tortured like that when they first arrived. A lot of the police officers had been with the Northwest Young Men’s Association, a group of defectors from North Korea, and they were the ones doing the torture.” Even now, a scar from his electric shock torture is visible on his right middle finger.

After being tortured, he was detained at the camp across the street from the Sehwa police branch. Oh and his parents spent at least two months interned there before the executions. The so-called “camp” was a former warehouse measuring around 23–26 square meters. Oh recalled that the internees at the time numbered 46.

“They kept people stuffed in that tiny room day and night. It was awful. I had to sit hunched over like the head of a bean sprout, holding my knees with my hands. With so many people incarcerated there, we had to sit like sardines.”

Continuing to do errands for the police who had killed his family, Oh lived for over two years at his uncle’s fertilizer distribution branch in Sehwa Village, making periodic stops in his home village. Returning to his empty home was like walking through a void.

Oh holds rites for his parents and siblings on the 12th day of the first month according to the lunar calendar. He also holds a rite for his older brother on the same day, although he does not know the date of his death.

“When my aunt laid out the offerings, she would bring it to the house and lay it out properly. I didn’t know how to do the rites so I would put the rice in a brass bowl and just stick a spoon in it, raise a glass, and do the service that way. It was after I got married that I started doing the formal rites.”

Of his life after being orphaned, Oh tearfully recalled, “When I was growing up, I suffered a lot of pressure and sadness from the people around me. It made my heart ache just to hear people talking about April 3. Every time I passed Yeondumang Hill, the memories would come back to me; even when I tried to ignore them, I would lower my head. Just looking at the hill made my heart hurt.”

Believing that the victims of Jeju April 3 “should receive the same kind of compensation” as victims of the events in Gwangju in May 1980, Oh was a founding member and active participant in the Association for the Bereaved Families of April 3 Victims. Every April 3, he takes his sons and daughters-n-law to attend commemorative ceremonies at Jeju April 3rd Peace Park.

By Huh Ho-joon, Jeju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 2Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 3[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 6Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 7New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 8Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 9Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors

- 10[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far