hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special report] S. Korea’s perception of youth exclusively applies to university students

“Waste” can be defined as the vain or prodigal consumption of one’s time or goods. That’s pretty much how Han Su-jeong (pseudonym), 23, an office worker, thought of university. “When you aren’t interested in studying, going to college is a waste of time. I figured I should just make some money,” she said.

While attending a humanities-focused high school in Busan, Han started working part-time at a buffet restaurant. Since then, she’s continued working at various restaurants and four different factories. For a while, she was juggling two jobs — after clocking out at the factory, she’d head to the evening shift at the buffet restaurant.

These days, she’s working six days a week, eight hours a day, at a logistics company in Busan. But she’s stuck on the night shift, which lasts from 9 pm to 6 am. Since she only works at night, she gets an extra allowance that brings her monthly wage to about 3 million won (US$2,520). Despite her insomnia, she doesn’t intend to return to the day shift, because she’s “extremely satisfied” with her current pay.

Han is throwing herself into her work like this because she’s not sure she could keep it up when she gets older. “If I keep working like this, I’ll eventually reach the point where my body can’t take it any longer. My idea is to work like this for now and then take it easy later. I want to own a building and live off the rent,” she says.

Han eventually hopes to come into possession of a five-story building. She’s set aside the first floor for an auto shop, which will be run by Chun Su-chan (pseudonym), her best friend since elementary school. She’ll rent out the other floors to coffee shops and outlets for computer and console gaming. On the roof, she plans to set up a camping spot, where she can stay up all night partying with her friends.

Han didn’t need a university diploma to achieve that dream, which is why she figured it would be better to get a job straight out of high school rather than moving on to university. “For one thing, I was able to save more money than kids who go to college. For another, I figured I’d have a better handle on office culture than college students,” she said. Han doesn’t see one’s educational background as being very important.

“As I see it, an impressive academic record doesn’t guarantee that someone will be good at their work, and not having that record doesn’t mean someone will be bad at it either.”

A diploma doesn’t guarantee certain job skillsThe future auto shop owner jumped into the conversation at this point. Chun Su-chan, 23, who is currently in an automotive program at a two-year college, recalled something that happened while he was teaching snowboard classes at a ski resort. “This guy who was going to a good university in Seoul came all the way down to Yangsan, in South Gyeongsang Province, to work for the season. I figured he’d be all over that job, right? But he wasn’t very good at it, and he kept goofing off. He was certainly proud of his university, though. So what, right? In the end I had to ask him to quit.”

Su-jeong picked up the thread at that point. “What does a ski resort have to do with college? College doesn’t teach you about every job.”

To be sure, there are some jobs that college can make you better at, but a university diploma doesn’t give people proficiency in all occupations. In the workplace, people have to do well and be diligent if they want to receive any credit for their work. That’s Han and Chun’s creed. The problem is that reality doesn’t care about their creed.

The difference in salary between high school and university graduates came home to Hong Su-ji (pseudonym), 22, when she got a job at a finance company straight out of high school. “Coworkers generally don’t know what their colleagues make, but I found out by chance. There was a big difference between my salary and that of a university graduate. It occurred to me that some kind of difference was inevitable,” she said.

“On top of that, one of my friends told me her bonus at work had been absurdly lower than the other employees. When she asked about it, the HR team insinuated — without stating this explicitly — that her bonus was lower because she only had a high school diploma. While working, I’ve often felt that there isn’t much of a difference in ability between university graduates and high school graduates. I guess that can’t be helped.”

When Su-ji was asked to rate the importance of having a university diploma and having attended a good university in Korean society on a scale of 1 to 10, she rated both at 10. “I think I’ve felt this more strongly than my friends because I joined the workforce so early. Educational background is ultimately directly connected with promotions and salary negotiations. Your alma mater seems to be important, too, because there are subtle differences in how companies treat you based on which university you attended and because of a tendency for managers to look after alumni from their own alma mater,” she said.

Sim Jeong-seok (pseudonym), 23, a university student, spent two years working for a hypermarket after graduating from a vocational high school in Incheon. She was making about 1.2 or 1.3 million won (US$1,008-1,092) a month. But colleagues who had graduated from four-year universities were making between 2.5 and 2.8 million (US$2,101-2,353) a month, nearly double her wages.

“The starting line is different depending on whether you graduated from a four-year university, a two-year college, or a high school. Your position in the company is different, and your wages are, too. I did stints in marketing and promotion and in logistics, and the high school graduates there all do the more physically demanding work. That’s when I realized I need to go to university,” Sim said. She’s currently studying distribution and marketing at a two-year college. After graduating, she believes, she’ll get a hard start over the competition.

Even eligibility for certain certifications requires university diplomaPaycheck size isn’t the only difference between high school graduates and university graduates. When Koreans talk about “young people these days” or “the youth,” the terms are synonymous with university students, and employment opportunities vary accordingly. Ahn Hyeon-jeong (pseudonym), 22, majored in accounting and media at a vocational school in Daejeon. She works as an office assistant while also freelancing as a video editor.

The people Ahn meets seem to assume that all young people are university students. “When I meet someone for the first time, they always think I’m a student. They ask which school I go to and what I’m majoring in. Everything seems to revolve around university graduates,” she said.

It wasn’t so bad when all Ahn had to worry about were hurt feelings. But there are so many things she can’t do without a university diploma. “Most of the things I’d like to do require a ‘university diploma or above.’ Most of the job postings for high school graduates or that don’t list an educational requirement are for part-time jobs. I’ve sometimes sent in my resume anyway, just to make a point. I’ve never gotten a response, of course.”

Ahn is certified as a computer graphics operator, but only those with a university diploma are eligible to receive the higher level of certification. The same is true for certification as a colorist. Ahn said it baffles her why society would place educational restrictions on the certificates for which she’s eligible. While this makes her angry, she knows that, in the end, she can’t change society and will have to adjust to it. That’s what Ahn has learned during the three years since she graduated from high school.

For such reasons, Ahn hopes to get into university. During her third year of high school, she was hired by a Daejeon defense contractor, but she eventually quit, unable to stand the overwhelmingly masculine atmosphere there. After that, she spent a year preparing an application for an art school, but she didn’t make much progress, and her parents said they couldn’t support her for another year. So now she’s juggling video editing and her job as an office assistant while she saves up for tuition.

“I was young for my grade, so I’ve basically been working since I was 18 years old. I don’t think it’s good for one’s mental health to join the workforce so soon. Conditions were so bad at the defense contractor I was working at that I’d head to the bathroom to bawl my eyes out every day. I was making about 1.6 million won (US$1,344) at such a young age, which was a scary amount of money. I gave all the money I made to my parents. My family was spending a lot of money on my older brother, who was in medical school, and our finances were rocky. I thought I should help out the family. But I think that spending so much of my time on the job has made me narrow-minded,” she said.

So Ahn hopes to study sociology at university. “Since I’ve only been doing design and editing my whole life, I want to do something I’ve never tried before. I think it’s important to learn several things at university. Setting aside whether it helps you get a job or not, I think it’s good for your character,” she said. As Ahn understands it, therefore, university is a place for learning about various things. But in reality, university is turning into a way to avoid discrimination at the workplace.

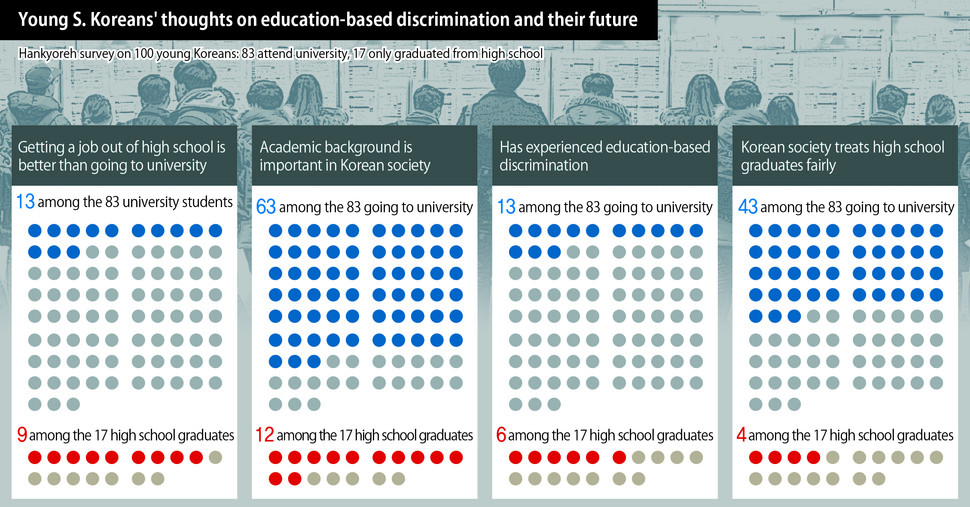

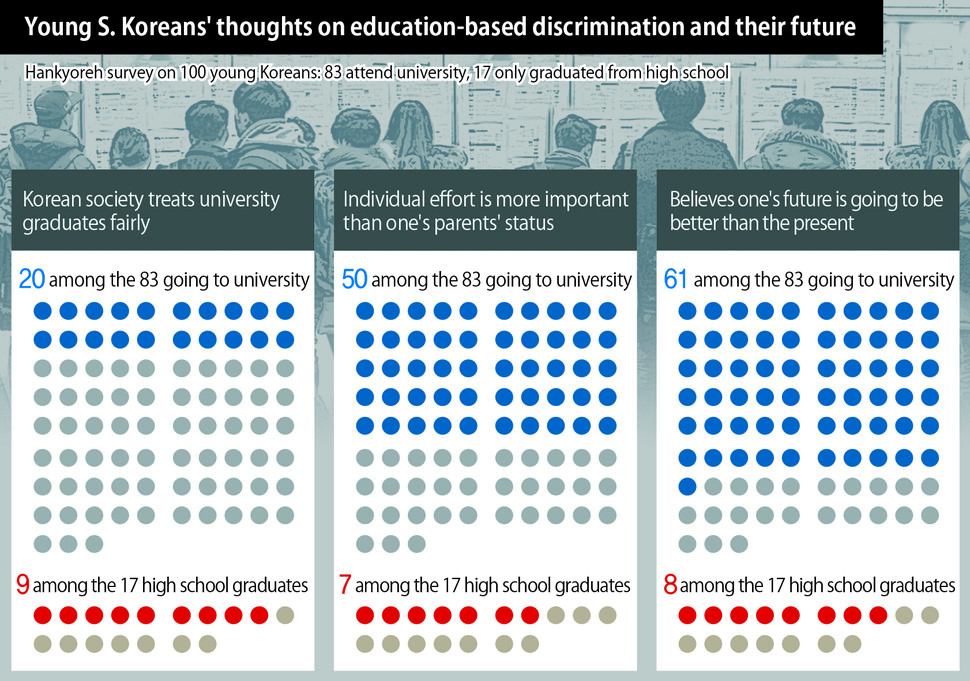

More than half of high school graduates who didn’t go on to university think it’s better to just get a job straight out of high schoolAmong the 100 people that we met, 83 were university students and 17 had either gotten a job or started a business after graduating high school or remained unemployed. When the Hankyoreh asked these 17 people whether they thought it was better to go to university after high school instead of getting a job, eight said it was and nine said it wasn’t. Among the eight who think it’s better to go to university, five justified their answer on the grounds that high school graduates have limited job opportunities. This hints at their desire to avoid the discrimination faced by those without a university diploma.

The nine who think it’s better to get a job right after graduating high school offered a range of opinions. “Some people might be confident that they’ll get into their desired university, but not everyone is able to do that, of course. It’s a waste of time if you end up going to a mediocre university,” said Cho Min-seok (pseudonym), 19, who is currently unemployed as he waits to begin his mandatory military service next month. As Cho is aware, even people who manage to avoid discrimination against those without a university degree will still have to face discrimination against those who didn’t go to a prestigious university.

“I know a lot of people who weren’t able to get a job even after going to college. That’s why I don’t get the idea that everyone has to go to college,” said Nam Min-su (pseudonym), 20, who works at the Banwon industrial complex in Ansan.

Park Ji-eun (pseudonym) 20, who works on the PR team at a distribution firm, takes inspiration from her aunt. My aunt on my dad’s side, who’s just two years older than me, graduated from a vocational high school and currently has a job at a securities firm. The impression I get from her is that, if you’re skilled at your job and work hard, not going to university doesn’t necessarily make a big difference. That’s especially true since high school graduates may well have job skills that have nothing to do with university education. There are some areas in which high school graduates might be even better than university graduates, since they learned practical skills in high school,” Park said.

There’s no reason to nitpick with Park’s remarks. Even so, the reality is daunting. Wages are still heavily affected by whether a worker has a university diploma or not. According to youth figures released by Statistics Korea and the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family this past May, the average wages of workers between the ages of 20 and 24 is 1,855,000 won (US$1,558), which breaks down to 1,790,000 won (US$1,503) for high school graduates, 1,824,000 won (US$1,532) for graduates of two-year colleges, and 2,015,000 won (US$1,692) for graduates of four-year universities.

“Young people” are defined as those who are in the middle of physical and mental development or who have just reached maturity. If all of South Korean youth were 100 people, only the 83 who go to university are counted as young people. And even they are represented by the 16 young people studying at four-year universities in Seoul. The number of young people who have a voice during times of political or social controversy, such as the Cho Kuk scandal, shrinks even further, to the two studying at the country’s most prestigious “SKY” universities.

But far in the background, completely out of sight, there are 17 other young people, living here in Korea, right now.

By Kim Hye-yun, Kang Jae-gu, Kim Yoon-ju, and Seo Hye-mi, staff reporters

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 3Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 4Gangnam murderer says he killed “because women have always ignored me”

- 5South Korea officially an aged society just 17 years after becoming aging society

- 6BTS says it wants to continue to “speak out against anti-Asian hate”

- 7After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 8No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 9Ethnic Koreans in Japan's Utoro village wait for Seoul's help

- 10US citizens send letter demanding punishment of LKP members who deny Gwangju Massacre