hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] The significance of Chun Doo-hwan’s trial

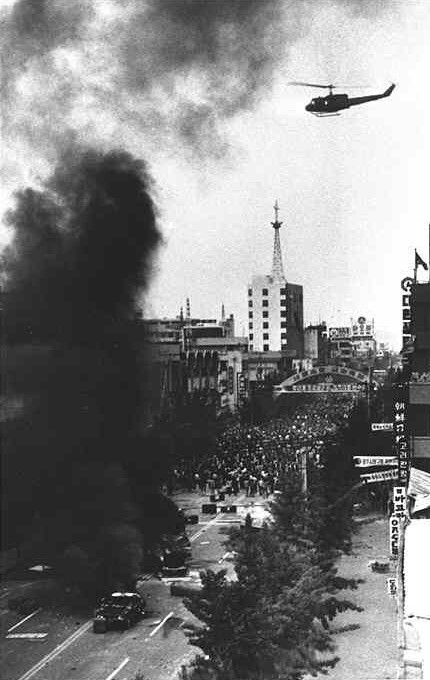

Appearing in a Gwangju court for the first time in a year on Apr. 27, former President Chun Doo-hwan, 89, was being tried on charges of defamation of the deceased for denouncing the late Catholic priest Cho Pius in his memoirs as a “shameless liar” after the latter claimed to have seen martial law forces firing on civilians from helicopters during the events of the May 18 Gwangju Democratization Movement in 1980.

The trial focused on two questions: whether the firing from helicopters actually occurred, and whether Chun was aware of it when he denounced Cho in his autobiography. If there was helicopter fire during the events of May 1980 and Chun was aware of it, the charges of defamation of the deceased were likely to hold up; if there was no fire, Chun was likely to be acquitted. Chun has maintained that there was no firing from helicopters, and that his use of the phrase “shameless liar” was a “literary expression.”

While Chun’s trial is officially considering the question of whether he defamed a deceased person, it’s also important in terms of uncovering the truth of the events of May 1980 -- since it concerns the question of whether the military leadership gave the order to open fire on civilians, which remains unanswered 40 years later. Chun and other former members of the leadership have been adamant in claiming that the martial law forces opened fire as an “exercise of self-defense” in the face of the citizens’ militia. But in contrast with fire by ground forces in a confrontation with the citizens’ militia, firing from helicopters would have constituted a unilateral form of attack that was a far cry from the “exercise of self-defense.” If the firing from helicopters was acknowledged to have taken place, the logic used by members of the military leadership would collapse.

In 2018, a Ministry of National Defense (MND) special commission investigating the events of May 1980 concluded that the martial law forces did engage in firing from helicopters between May 21 and 27, 1980. The commission saw the helicopter fire witnessed by Cho on May 21 as evidence of the martial law forces’ brutality and criminal behavior.

“Helicopter fire is the sort of thing that would only be an option in wartime, and as evidence it instantly demolishes the ‘self-defense’ argument and the idea that [the martial law forces] only opened fire to protect themselves,” said attorney Kim Jeong-ho, a legal representative for the plaintiffs.

“For helicopter fire to have taken place on [May] 21, there would have to have been a plan for use of the helicopters, which would have had to been armed beforehand. On that basis, we have to conclude that there was an order [by the martial law army leadership] to open fire ahead of time,” he argued.

But despite the numerous eyewitnesses and the emergence of operational guidelines and prior plans associated with helicopter fire, no records of actual fire have yet been discovered -- leaving the question of whether the firing actually took place a matter for a heated courtroom battle. During the trial, the helicopters’ pilots denied that its marksmen fired upon civilians, maintaining that they “made armed sorties but did not open fire.”

Noe Young-gi, a Chosun University professor who served as an investigator for an MND truth and reconciliation committee investigation in 2007, said, “Chun Doo-hwan was in control of the military and country, and there’s no chance he would have left any records that would incriminate him.”

“But while the prosecutors have to approach things logically to prove the charges of defamation of the deceased against Chun, there’s no way of knowing how the court will decide,” Noe said.

In connection with this, a document titled “Army Training & Doctrine Command Loyalty Operation” acquired by the Hankyoreh on Apr. 26 showed the martial law command assigning five armed 500D helicopters for a “re-entry” operation that involved an armed suppression of the Gwangju area on May 27, 1980. The document suggests a possibility that armed helicopters were deployed through the suppression operation in May 1980.

Prosecutors requested the presence of related experts and witnesses to prove that the firing from helicopters took place. They included Kim Dong-hyeon, head of firearms research at the National Forensic Service, who studied bullet marks on the Jeonil Building; Kim Hee-song, a research professor at the Chonnam National University May 18 Institute, and David Dolinger, a former US Peace Corps member who claimed to have witnessed soldiers open fire on civilians from a helicopters. The court also planned to request that the person who wrote the MND special commission investigation report appear as a witness.

Assuming that one hearing is held every three weeks as has been the case to date, sentencing in the first trial appears likely to take place sometime around September of this year. Another possibility is that the court will delay its decision until the current May 18 investigation committee has completed its activities.

In April 2017, the May 18 Memorial Foundation and others filed a criminal suit against Cho accusing him of defamation of the late Cho Pius. The Gwangju District Prosecutors’ Office indicted Chun without detention in May 2018. In January 2019, a court issued an arrest warrant for Chun over his failure to appear at criminal hearings; Chun subsequently appeared for questioning that March. After declining to appear for subsequent hearings, citing “health issues,” Chun was appearing in the court for a second questioning session as a defendant after the judge hearing the case was replaced.

By Kim Yong-hee, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 3AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 4[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 5Noting shared ‘values,’ Korea hints at passport-free travel with Japan

- 6Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 7Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 8Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 9The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 10Yoon says collective action by doctors ‘shakes foundations of liberty and rule of law’