hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] The individual stories of pain amid the Gwangju Democratization Movement

Lee Gwi-im lost her husband to soldiers’ gunfire and her sons to forced adoption

The May 1980 Gwangju Democratization Movement is now marking its 40th anniversary, but many continue to call for a thorough investigation of the facts and punishment of those responsible for the slaughter of civilians. The Hankyoreh decided to look at the stories of lives plunged into disarray by the brutal violence of the military regime at the time, focusing on five key themes: separation, pain, forgetting, repentance, and revival.

In addition to the members of the public, the ordinary soldiers who were ordered into Gwangju are also victims of history, and their anguish continues to this day. This series looks at five stories from the vantage point of the 40th anniversary of May 1980.

Her husband left her behind that month, killed by a martial law soldier’s bullet on Geumnam Road. It happened on May 21, 1980 -- the day the troops opened fire on the citizens of Gwangju.

“When I was told my husband was dead, I thought it was a lie,” said Lee Gwi-im, 67, as she met with the Hankyoreh in Anyang, Gyeonggi Province, on Apr. 18. She learned the tragic news only belatedly, having taken their two sons to stay with her sister-in-law in Naju’s Yeongsanpo township.

“When I boarded the bus at Gwangju Terminal to go to Yeongsanpo, I had no idea things in Gwangju would get so chaotic,” she recalled. Hampered by the martial law troops’ controls, she was unable to even claim the body.

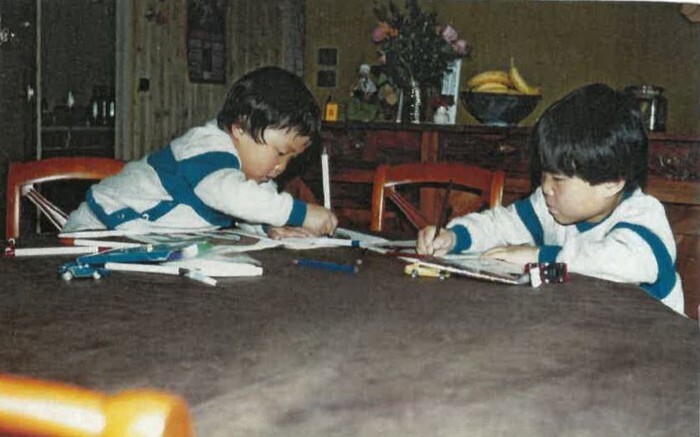

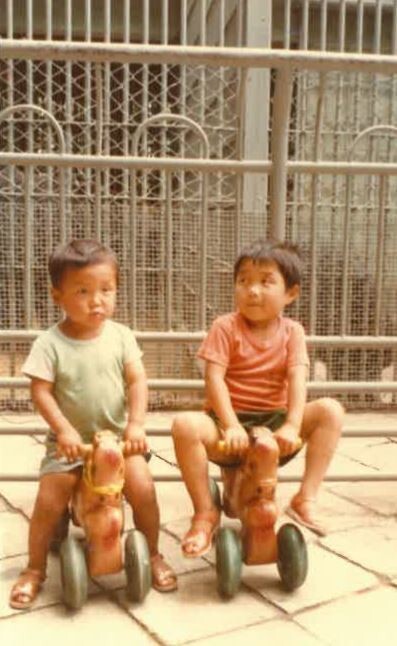

Lee had been living in Gwangju after being orphaned at an early age. She met her future husband, the late Jeong Hak-geun, through an acquaintance in 1973. They began their life as newlyweds in Bupyeong, Gyeonggi Province, and had two sons in 1975 and 1977. Around March 1980, they relocated to Gwangju, where they were living in a rented room when the events of May 1980 unfolded. They had been there at the Asia Motors factory (now Kia Motors’ Gwangju factory) when Gwangju citizens came out dragging a military vehicle behind them.

“When no family members came forward, my husband’s remains were buried in Mangwol-dong Cemetery without any funeral procedures,” she said.

The widowed Lee did whatever she could to keep food on the table for her two sons. She cooked corn and sold it off of a hand cart, and she peddled chicks. With no money to rent a room, she spent months on end living in a tent in the hills behind the Nongseong neighborhood. The older son attended elementary school, but Lee ended up being defrauded, leaving her in dire straits. Feeling compassion for her plight, a minister informed her about an orphanage located in Mokpo.

“When they said they’d put my children through middle school, I decided to place them there temporarily so that I could just get through that difficult time,” she remembered.

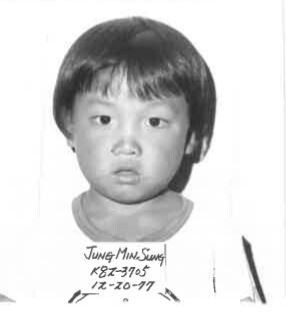

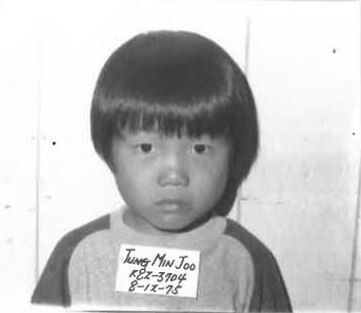

After that, things continued to go downhill. Three months later in February 1983, she went to the orphanage bringing clothes she had bought for her sons, Jeong Min-ju (born Sept. 17, 1975) and Jeong Min-seong (born Dec. 20, 1977). But neither of them was there. The orphanage told her they had been “sent to Seoul.”

“I was just stunned. I asked, ‘Why were they sent to Seoul?’ and they told me they were being put up for adoption through Holt Children’s Services in Seoul.”

The news came like a bolt from the blue. Lee raced to Seoul as fast as she could, but the two boys had already left for France.

“I never said I was putting them up for adoption, yet they had it listed that I had given written consent. It wasn’t my handwriting,” she said. “I didn’t know how to write at the time.”

Second chance at marriage shut down by in-laws’ opposition

After that, Lee lost her will to live, her mind and body growing increasingly haggard. As she began hallucinating and suffering lingering discomfort, she even consulted a shaman for a traditional exorcism ceremony. In the middle of all of this, she met someone. After becoming engaged to a heavy equipment operator who would become her second husband, she went to live with his family in Boseong, South Jeolla Province. But her in-laws opposed the marriage, having learned that her first marriage had “failed.”

Four months pregnant, she left the home without a word to her husband. Swallowing her tears, she gave birth to a daughter on her own, listing the girl in the family register under her own surname.

“I’ll always feel bad to my daughter for making her live her life without anyone to call ‘father,’” she said.

May 1980 left Lee’s life in ruins. At one point, she traveled with other surviving family members to Chun Doo-hwan’s home in Seoul’s Yeonhui neighborhood to demonstrate. She recalled feeling angry with herself for being “so powerless because I couldn’t beat him to death.” Twenty-five years ago, she moved to Anyang, where she worked for years at a restaurant. Fortunately, her daughter was a good student who was able to earn scholarship money and graduate from university with an English major. Now working an irregular job as a cleaning staff member at a hospital, Lee said her sole joy is going to visit her daughter in Seoul on weekends with home cooked side dishes.

Living off the hope provided by her daughter

“Things are so grim that I don’t know how I’d make it through if it weren’t for my daughter. She gave me a reason for living.”

Her feelings of frustration remain -- especially with regard to her two sons.

“It’s just like having heartburn. I always have that feeling in my chest,” she said.

“My older son had already begun coming of age. He told an employee at the orphanage, ‘My mom’s very sick, and I’m going to become a doctor so I can heal her.’ I cried so much when I heard that he’d been sent away [for adoption].”

Around 20 years ago, Lee visited Holt Children’s Service in Seoul, but was only able to determine vague information about her younger son, she said.

“To be honest, I don’t think I would have the strength to handle it if I did know my sons’ addresses now. But I would at least like to hear that they’re doing well.”

By Jung Dae-ha, Gwangju correspondent reporting from Anyang

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 3[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 4Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 5Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 6[Special Feature Series: April 3 Jeju Uprising, Part III] US culpability for the bloodshed on Jeju I

- 7[Column] America must frankly own up to role in tragic Jeju April 3 Incident

- 8‘My mission is suppression’: Jeju blood on the hands of the US military government

- 9Dermatology, plastic surgery drove record medical tourism to Korea in 2023

- 10[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis