hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Korea’s institutionalization of disabled people during the COVID-19 era (Part 1)

Lee Jung-ha says for the past 20-years she’s heard voices that sometimes insult her or urge her to commit suicide.

These 50 disembodied speakers first started talking to her when she worked in the animation industry, she says. But when Lee sought professional help for schizophrenia at that time, she was given no choice; her doctor and parents committed her to a closed psychiatric ward.

That began a cycle of recovery, release, relapse and readmission by force, she explains.

“One time my family told me we were going to the mountains and when we arrived, men abducted me and took me to a hospital,” she says.

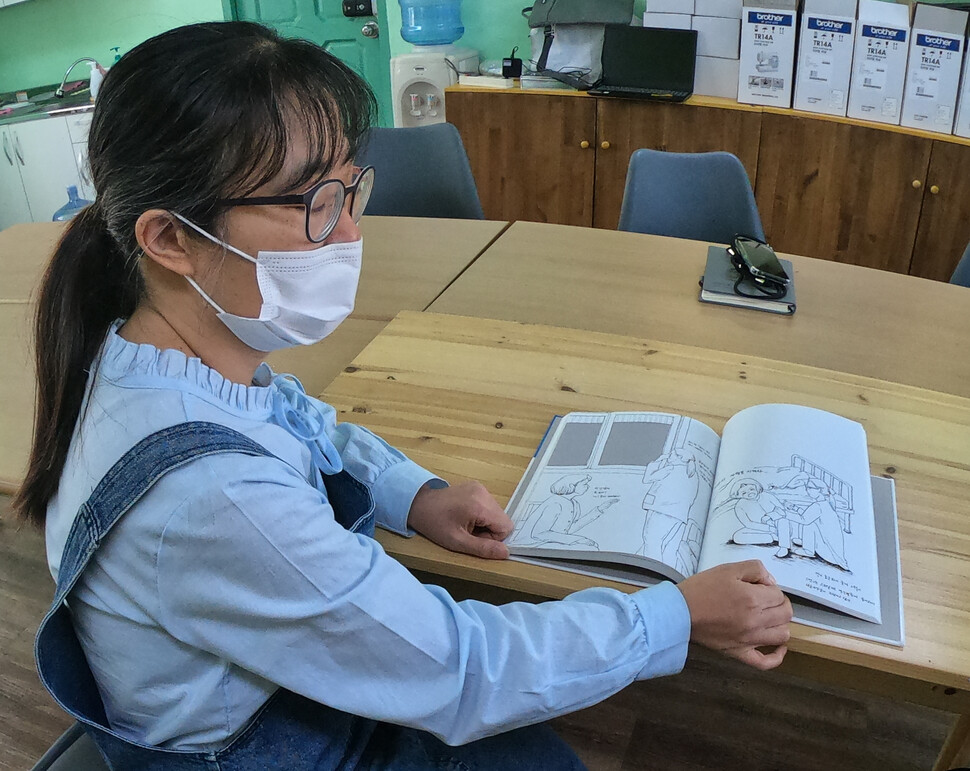

During one of those admissions, Lee was able to get a hold of a felt-tip marker and sketched a depiction of the living conditions inside the unit, where she says a hundred patients lived packed together on each floor. Black-out shades were drawn over the windows and lights were always turned on, she recalls.

A copy of that impression and other pictures she’s drawn from her memories of undergoing psychiatric treatment are printed in a book she keeps at her office in Seoul. But Lee says there’s one scene still etched in her mind that she can’t bring herself to recreate.

At one center, she alleges staff tied her feet and hands to a bed and injected her with an unknown medication that “just knocked me out,” she says.

“It’s too traumatic to draw,” says the 49-year old.

Lee now heads the advocacy group Padosan and claims many institutionalized people with mental health disorders reside in similar conditions against their own will and also experience the same human rights abuses.

And during the COVID-19 pandemic, she says, life in these kinds of facilities has become even more precarious, if not deadly.

South Korea’s first official COVID-19 death occurred inside a psychiatric care unit in February 2020. The infection cluster at the Cheongdo Daenam Hospital in North Gyeongsang Province spread through the closed ward, killing eight and infecting all 102 patients, according to the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA).

A separate probe into the incident by the National Medical Center found that the disease’s “transmissive power” was strengthened by factors including inadequate ventilation, the inability to physically distance, and poor personal hygiene. It also pointed to high instances of respiratory or other pre-existing illnesses among residents as well as the difficulty some patients had expressing symptoms due to mental illness.

Some media dispatches from the medical center showed bars placed over locked windows, tight sleeping arrangements on the floor and a limited number of restrooms.

For Lee, these images were not surprising; she says that she and other activists have tried for years to raise awareness about the types of conditions that led to these deaths. And since that outbreak, advocacy groups like Padosan have renewed their longstanding call for the closure of closed psychiatric wards and other institutions that they say “imprison” people with mental, physical and developmental disabilities.

Heightened risk of infection and deathIn South Korea, tens of thousands of people with a wide range of disabilities currently live in long-term residential care centers and hospital wards — the kinds of facilities that health experts and rights groups say exacerbate an individual’s vulnerability to the disease.

In April, as the first wave of COVID-19 spread across many countries, the UN warned that people with disabilities who live in residential care facilities face “heightened risk” of infection due to underlying health conditions and the inability to socially distance, and are more likely to experience “human rights violations such as neglect, restraint, isolation and violence.”

Official data on how the pandemic has impacted this global population is scarce, but reports in American and European media as well as from international advocacy organizations suggest a disproportionate infection and death rate.

In the wake of the outbreak at the Cheongdo Daenam Hospital, South Korea’s health authorities issued preventative guidance to care facilities that puts restrictions on movement to and from these centers.

The Ministry of Health and Welfare (MOHW) says as of Oct. 19 residents of group homes for the disabled who had contracted the coronavirus and have all recovered.

Officials at the KDCA and MOHW say they do not track coronavirus transmissions in psychiatric units.

While South Korea has avoided the high number of COVID-19 infections and death rates of many other countries, the Cheongdo hospital outbreak pulled back the curtain on a system that many disability advocates and formerly institutionalized people say was already unsafe and dehumanizing, but goes largely unnoticed.

Institutionalized people with disabilities are a segment of the population the general public normally “pays little attention to,” says Seo Won-sun, a researcher at the state-affiliated Korea Disabled People’s Development Institute in Seoul.

Social stigma has led to psychiatric hospitals being placed in isolated areasHe says large institutions for the disabled and psychiatric hospitals are considered “socially unacceptable” on the same level as “cemeteries and garbage dumps” — places that most people don’t want near their homes. There’s also a prejudiced notion, Seo adds, that people with mental disorders or who have autism are violent and pose a danger to public safety.

For those reasons, many of these centers have been placed in isolated areas, far away from communities as well as from scrutiny, he explains.

Approximately 66-thousand patients were admitted into open and closed psychiatric wards in 2018, according to the most recent data from the National Center for Mental Health.

Some 25,000 people with physical and developmental disabilities currently live in institutional settings, according to the government’s latest figures. Seo says about 75% of this population has an intellectual impairment or an autism spectrum disorder.

The Cheongdo Daenam Hospital’s COVID-19 outbreak could serve as a “starting point” to reevaluate the role of residential care facilities, Seo says, but worries that once the coronavirus pandemic is over, the public and politicians might “forget everything” about these centers.

Nine months after the country’s first COVID-19 death, the Cheongdo Daenam Hospital appears to be distancing itself from the group infection that took place in the early days of the pandemic.

When visitors arrive at the private medical center, they first pass through a makeshift white tent and ascend a small flight of steps that lead to the hospital’s only open entrance. Staff at the doorway check temperatures and inquire about other potential coronavirus symptoms.

Some arrivals heading to an elderly-care unit carry bags of snacks and packs of adult diapers.

There’s no signage or other indicators of the psychiatric ward that had occupied the building’s fourth floor. A woman registering guests claims she knows nothing about such a unit.

The mental healthcare facility is still an option on the hospital’s automated answering service, but calls go unanswered. An employee who picked up the phone for another extension said the psychiatric treatment center is no longer in business.

Hospital officials did not respond to multiple requests to comment for this report.

The KDCA initially linked the deadly outbreak here to a coinciding super-spreader event at the Shincheonji religious sect’s church in Daegu, but in September, officials announced they are re-examining that connection.

The agency didn’t release the name of the first patient to succumb to the disease on Feb. 19, but reported that he was 63 years old, diagnosed with schizophrenia and had lived at the hospital for 20 years.

Around 1/3 of mental patients have spent 10 or more years in psychiatric hospitalConcerns over lengthy admissions to psychiatric wards have recently been raised by the National Human Rights Commission of Korea.

In an investigation that looked at the conditions of roughly 9,500 mental healthcare patients, the government watchdog agency reported in September that one-third have spent 10 or more years in a psychiatric hospital. Of that total, 40% were admitted by a guardian and cannot be released on their own accord.

The commission has called on health authorities to abolish involuntary admissions and to transform psychiatric institutions into community care centers that house fewer patients in a less-confined setting.

MOHW’s mental health policy division did not make an official available to answer questions for this report.

Attempts have been made to reform the country’s psychiatric care system. The Mental Health Welfare Act was revised in 2017 in part to limit involuntary hospitalizations by requiring the consent of two doctors to admit patients that show risk of self-harm and who require treatment under supervision.

There are 1,670 psychiatric care facilities nationwide, government data shows.

Hospitals financially incentivized to keep patients admitted in closed wardsActivist Lee Jung-ha says not all psychiatric units abuse or neglect patients. But she claims some private hospitals fail to provide adequate psychological or medical care and are financially incentivized to keep patients admitted for as long as possible in closed wards.

“There has to be change to this system,” Lee says. “Once someone with a mental health disorder enters these hospitals, they might never get out again.”

Mental patients often shunned or abandoned by their familiesSome people with physical and developmental disabilities also spend their entire lives in institutions, researcher Seo Won-sun says, adding that up until a few decades ago, it was not uncommon for parents to “abandon” their disabled children in large care facilities.

But some families still cut off all contact with their institutionalized adult relatives, he says, going as far as to change their addresses and telephone numbers.

“It’s unfortunate,” he says. “They just die (in the institution) and no one comes to the funeral.”

“This is the tragic history of disability,” in Korea, he says.

Seo says many Korean families continue to send disabled loved ones to long-term care centers because the cost for home care could be prohibitively expensive and government support for assistive services is lacking.

Depending on the severity of the impairment, Seo explains that an individual could require around-the-clock assistance, but the government might subsidize only a fraction of the cost to hire a full-time caregiver if they live with relatives.

“That means a family member has to take care of that child, quit their jobs and stay at home every day,” he says. “And that can cause emotional or psychological stress for the parents.”

Categorized as “economically useless”Some other observers say this economic pressure underscores the stigma of disability in Korea.

People who cannot demonstrate their economic “productivity” are regarded as “useless,” says Byun Jae-won, policy director at Solidarity Against Disability Discrimination.

He says entire families can feel this strain.

“They feel burdened by a disabled child, that the child makes them unable to survive in the jungle,” Byun says. “This is why some families think it safer to keep their disabled children in institutions.”

And for some families, like his, a disabled child is an embarrassment.

“My mother always told me that I am a shame to the family,” says Byun, who uses a pair of crutches while walking.

The 27-year-old explains that he contracted a spinal disease as an infant, but was never institutionalized, though he speculates his mother, whom he no longer speaks to, might have preferred that.

“She’d say, I want you to just stay at home and be invisible.”

By Jason Strother, freelance journalist

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

This work was supported by the National Geographic Society’s Emergency Fund for Journalists

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8917132552387962.jpg) [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces![[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0416/8317132536568958.jpg) [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

- [Editorial] Koreans sent a loud and clear message to Yoon

- [Column] In Korea’s midterm elections, it’s time for accountability

- [Guest essay] At only 26, I’ve seen 4 wars in my home of Gaza

- [Column] Syngman Rhee’s bloody legacy in Jeju

Most viewed articles

- 1Faith in the power of memory: Why these teens carry yellow ribbons for Sewol

- 2[Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- 3[Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- 4[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 5Korea ranks among 10 countries going backward on coal power, report shows

- 6Final search of Sewol hull complete, with 5 victims still missing

- 7[News analysis] Watershed augmentation of US-Japan alliance to put Korea’s diplomacy to the test

- 8K-pop a major contributor to boom in physical album sales worldwide, says IFPI analyst

- 9World famous Korean instant noodle: truth and misconceptions

- 10Japan ramps up efforts to remilitarize, integrate with US to deter China