hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

How young university student, full of dreams, died in tragic workplace accident

There were a lot of things the 23-year-old university student wanted to do. He wanted to make money to buy snacks for his nieces and nephews. He wanted to treat his family to noodle soup. He was considering becoming a math teacher, but he also thought he might be better off studying a technical skill because of the shortage of jobs.

He was an ordinary young man. He wanted to lighten the burden on his father and mother, who respectively worked at the Pyeongtaek Port and a restaurant.

On April 22, Lee Seon-ho’s dream came to an end.

While working part-time to check the contents of shipping containers at the port of Pyeongtaek in Gyeonggi Province, he went to remove a piece of wood that had gotten caught in the body of the openly structured container. The container’s 300-kg wing came down on him, crushing him to death.

At the time, there was no safety management official or signal operator with him. He had been sent in to do something for the first time without undergoing any safety training.

What sort of life might the 23-year-old have led if he hadn’t died such a pointless death? How were the future of a young man and his family irrevocably changed by a lack of concern for workplace safety?

The Hankyoreh reconstructed his life and dreams based on the information shared about him by his sister Lee Eun-jeong, 29.

Each of Lee Seon-ho’s family members called him by a different nickname. His mother called him “Prince Seon-ho.” His father called him “Jjukkumi,” after a type of small octopus. His sister called him “Jjanggu,” meaning “bighead.”

He had two older sisters, aged 31 and 29. The older of the two has an intellectual disability, and Lee Seon-ho was a dependable brother who looked after her like her guardian.

“If he saw people making fun of our sister or something, he would confront them. He would make stuff for her to eat, and he’d stand outside when she was crossing the street. It was so moving to see things like that,” Lee Eun-jeong said.

“Our sister was very sick recently, and Seon-ho would always comfort the family in our struggles. He’d say things like, ‘Her treatment’s going well these days. Don’t look at things too negatively,’” she said. “I later learned that he would cry a lot when talking about his family with his friends.”

Lee Seon-ho had hoped to make things easier on his parents.

“He felt bad taking spending money from them when he went to university,” Lee Eun-jeong explained about his decision to start working part-time alongside his father at the Pyeongtaek Port in January 2020. He used the money to pay rent on a small apartment he shared with friends.

“Seon-ho would give his nieces and nephews 50,000 won (US$44) to buy food for themselves,” she said.

“I asked him where he got the money for that, and he told me he’d been doing a lot of work at the Pyeongtaek Port and was making a bunch of money,” she added. “Whenever he earned money, he wanted to give more to the people in his life.”

Lee Seon-ho was high-spirited. He liked to sing and play the guitar. He even learned how to play the contrabass in high school.

“He’d always finish in first place or as runner-up at the school festival talent shows,” Lee Eun-jeong said.

He was especially strong in math.

“His math teacher was surprised when he would go up to the blackboard and solve something even the teacher didn’t know. He talked about wanting to be a [certified public accountant] or a tax accountant.”

He was a strong student who earned a scholarship when he entered the math department at his university. At home, he was “the only one of the kids who studied.”

Hearing that it might be difficult for him to find a job, he debated whether to learn a skill instead. His father, who had worked for some time as the head of a work group at the Pyeongtaek Port, advised him to carry on with his studies. “Technical jobs are difficult and dangerous,” he told his son.

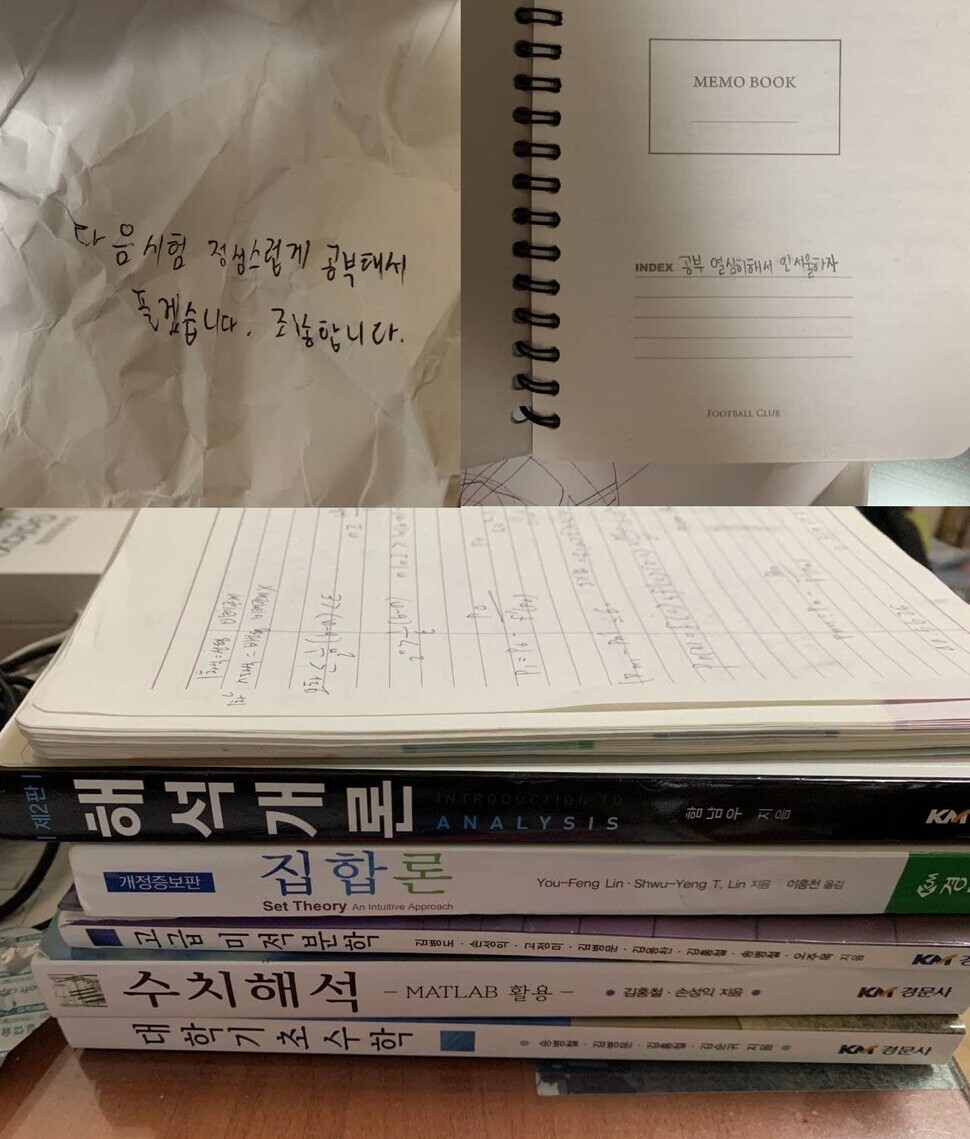

On the day of the accident, Lee Seon-ho had brought his laptop and notebook to study for a test. The pages of his notebook were filled with equations. A few days later, his items were returned — not to their now-gone owner, but his father.

“I’d gotten a video call from Seon-ho that day,” Lee Eun-jeong said. “I was showing him my kids and talking, and I told him he would talk later because I had to tend to my kids. I thought we’d be able to talk again whenever.”

That evening, Lee Seon-ho’s mother waited at home with the “seasoned spinach and bean sprouts he liked.” When she called up Lee Eun-jeong crying that Lee Seon-ho was dead, her daughter’s first thought was, “Why would mom lie like that?”

Lee Seon-ho’s oldest sister has been waiting for her brother’s return for over two weeks now. It’s become a habit for her to ask, “When is Seon-ho coming back?”

Her family members aren’t ready to tell her the truth. So far, they have been saying that he has “gone to take a test.”

A family hopes for an investigation before letting goLee Eun-jeong said the family is now prepared to say goodbye to her brother. They are hoping for an acknowledgment by the forklift operator with Dongbang who ordered Lee Seon-ho to go up on the container.

“My parents were working to earn money to support my brother, and now he’s gone. Even a hundred billion won wouldn’t do him any good,” she said.

“We want the company to admit what happened and apologize sincerely. My mother has been saying, ‘Your brother always hated cold places. How long is he going to have to stay there?’”

Eighteen days after the accident, the funeral had not been completed because Lee Seon-ho’s family believed there needed to be an investigation.

His family members hope that no one else has to experience the same kind of suffering.

“He was so young. He was just entering the prime of his life. It’s such a waste. We don’t want this sort of thing to happen to anyone else.”

By Shin Da-eun, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/7417158465908824.jpg) [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence![[Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/4417158464854198.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

[Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation- [Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- [Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- [Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

- [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

Most viewed articles

- 1Could Korea’s Naver lose control of Line to Japan?

- 2[Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- 3[Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- 4Naver’s union calls for action from government over possible Japanese buyout of Line

- 5[Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- 6Korea cedes No. 1 spot in overall shipbuilding competitiveness to China

- 7[Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

- 8[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

- 9Korean opposition decries Line affair as price of Yoon’s ‘degrading’ diplomacy toward Japan

- 10Second suspect nabbed for gruesome murder of Korean in Thailand, 1 remains at large