hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

How Bush set stage for N. Korean nuclearization

The terrorist attacks committed in September 2001 by the Islamic fundamentalist terror organization al-Qaeda had tremendously complex repercussions that extended not only to US policies in the Middle East, but also to the Korean Peninsula on the other side of the globe.

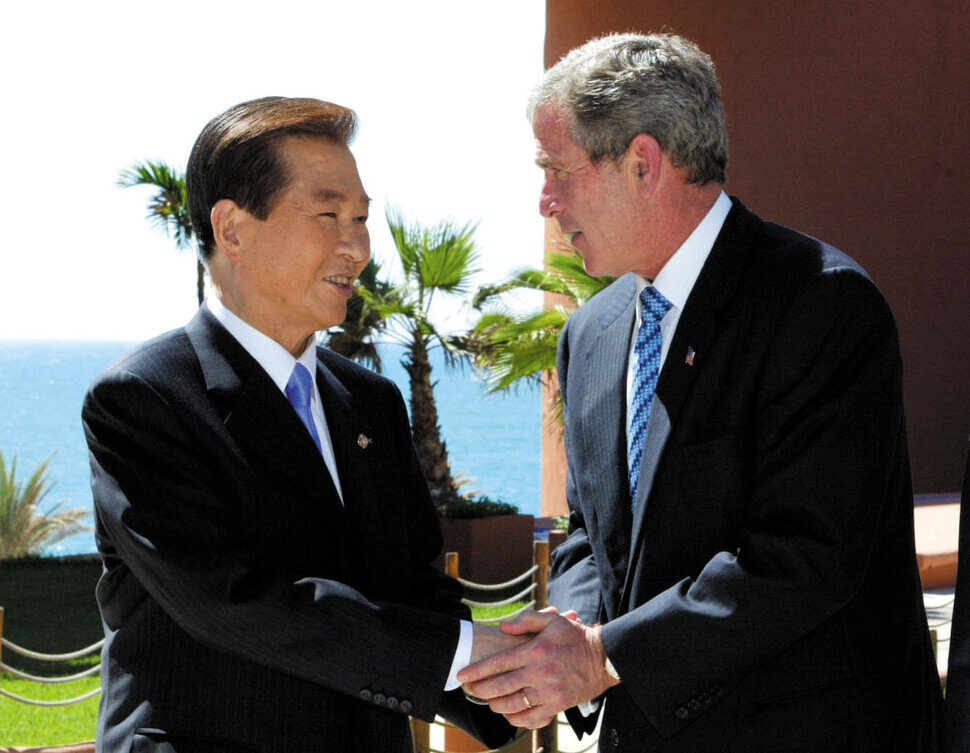

The administration of then-President George W. Bush, who took office in January 2001, undertook major revisions to the North Korea policies implemented by his predecessor Bill Clinton, who had largely yielded the driver’s seat to then-South Korean President Kim Dae-jung.

Concerned about the influence of the neocons surrounding Bush, Kim moved the date of the first South Korea-US summit up to early March, rather than its usual date in May or June. He sought to win Bush’s support, but did not succeed.

In his memoir “Pot Shards,” former US Ambassador to South Korea Donald Gregg shared a scathing assessment.

“[Bush’s] misguided, ideological approach to North Korea brought to a tragic and totally unjustified end significant progress made in the wake of the Pyongyang Summit meeting [of June 2000] in developing new relations with North Korea by both Seoul and Washington,” he wrote.

But even then, North Korea’s nuclear development program remained off-limits due to the Agreed Framework reached by North Korea and the US in Geneva in October 1994. The huge shock of the 9/11 terror attacks ended up blowing that seal wide open.

After witnessing the collapse of the World Trade Center towers in Manhattan, Bush immediately invaded Afghanistan. In his State of the Union Address in January 2002, he referred to North Korea in conjunction with Iran and Iraq as part of an “axis of evil.”

The death knell for the Agreed Framework was sounded that October when James Kelly, the assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, visited Pyongyang and raised allegations of nuclear development using highly enriched uranium.

The dam holding back North Korea’s nuclear program was breached, and the Joint Declaration issued by Kim Dae-jung and then-North Korean leader Kim Jong-il on June 15, 2000, was reduced to scrap paper.

In his book, Gregg recalls something he told North Korean general Ri Chan-bok to explain the emotions running through the US at the time.

“I wondered how he would feel if he were to see one of his own commercial aircraft deliberately crash into the [Juche] tower [in Pyongyang], reducing it to rubble. I said that the people of the United States had seen that happen twice in New York on 9/11,” he writes.

Subsequently, the North Korean nuclear issue reached a point beyond repair.

North Korea went on to conduct six nuclear tests. In late November 2017, it declared the “completion” of its nuclear armament with the successful test-launch of the Hwasong-15, an intercontinental ballistic missile capable of striking Washington.

Another effect that 9/11 had on the Korean Peninsula concerned the agreement on “strategic flexibility” for the US forces stationed in Korea (USFK). The US demanded this flexibility, which would allow for the use of the USFK to conduct Iraq War operations more smoothly; after wrestling with the matter, Seoul acquiesced.

In January 2006, the Roh Moo-hyun administration agreed to respect the need for the strategic flexibility of the USFK. A decade and a half later, that agreement has been posing a different sort of burden on South Korea as the East Asia situation heats up amid the strategic rivalry between the US and China.

During his confirmation hearing in May, USFK Commander Gen. Paul LaCamera said, “United States Forces Korea forces are uniquely positioned to provide the Commander USINDOPACOM [US Indo-Pacific Command] a range of capabilities that create options for supporting out-of-area contingencies and responses to regional threats.”

This means that if an armed clash were to take place between the US and China over a matter such as Taiwan, South Korea could find itself drawn into the conflict one way or another.

By Gil Yun-hyung, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 4[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 5[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 6Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 7[Editorial] When the choice is kids or career, Korea will never overcome birth rate woes

- 8Constitutional Court rules to disband left-wing Unified Progressive Party

- 9Nearly 1 in 5 N. Korean defectors say they regret coming to S. Korea

- 10‘Right direction’: After judgment day from voters, Yoon shrugs off calls for change