hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Can Yoon’s plan for N. Korea’s nukes really be called a plan?

How did South Korea end up living under the threat of North Korea’s nuclear weapons?

It seems like the sort of obvious question that everyone already knows the answer to — but isn’t. The history and background of North Korea’s nuclear program is far from straightforward.

North Korea first began developing an interest in nuclear capabilities during the 1950s. The direct impetus is said to have come from General Douglas MacArthur’s threats of using nuclear weapons during the Korean War.

In 1956, North Korea signed an agreement with the Soviet Union on the establishment of a joint nuclear research center. It sent scientists to learn about theory and practice concerning electronics, radiochemistry, and reactors.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the North laid the groundwork for nuclear weapons development through institutional changes, the training of an expert workforce, and expansions to its facilities, including the creation of a nuclear research complex at Yongbyon and the acquisition of a research reactor. By 1975, it had already acquired technology for reprocessing spent nuclear fuel.

It was during the 1980s that it truly began developing its nuclear capabilities. It constructed facilities for reprocessing spent fuel to extract plutonium, and it went about reprocessing in secret.

The North’s nuclear capabilities were revealed to the rest of the world in 1989 when a French commercial satellite shared footage it had taken of the Yongbyon nuclear facilities.

North Korea had been a member of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) since 1974 and had ratified the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 1985, and it now came under intense pressure from the international community. This happened to occur around the same time the US was withdrawing its tactical nuclear weapons from around the world following the end of the Cold War.

The US likewise withdrew the tactical nuclear weapons it had deployed with US Forces Korea. In December 1991, South and North Korea announced their Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

But after that joint declaration, a conflict erupted between the US (as represented by the IAEA) and North Korea over inspections of the North Korean nuclear facilities. In 1993, the North declared its withdrawal from the NPT.

This was the first North Korean nuclear crisis. It was finally quieted with the Agreed Framework reached between North Korea and the US in Geneva in October 1994, and Pyongyang reversed its decision to withdraw from the NPT.

After visiting the North as a special presidential envoy in 2002, then-US Assistant Secretary of State James Kelly alleged that it was developing nuclear weapons with highly enriched uranium. The George W. Bush administration suspended its execution of obligations according to the Agreed Framework, including heavy crude oil assistance, and North Korea objected.

This was the second North Korean nuclear crisis. Pyongyang expelled the inspectors and once again declared its withdrawal from the NPT. The Agreed Framework had collapsed.

In 2003, the first six-party talks were held, with South and North Korea taking part alongside the US, China, Japan and Russia. Thanks to proactive mediation by chair nation China, an agreement was reached on Sept. 19, 2005.

The most important terms of the joint statement of September 2005 had to do with the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.

But that statement ended up going up in smoke too when the US announced that North Korea had been distributing counterfeit dollars and laundering illegal international transaction funds through Banco Delta Asia. Relations between Pyongyang and Washington soured, and the North conducted its first nuclear test in October 2006.

Since then, it has been all downhill for the North Korean nuclear issue. North Korea carried out its second nuclear test in May 2009, its third in February 2013, its fourth and fifth in January and September 2016, and its sixth in September 2017.

As this shows, the North Korean nuclear issue is a complex matter with a history and background that goes back a long time.

Who’s at fault for North Korea’s nuclear weapon development?

North Korea, obviously. Its development of nuclear weapons is an unacceptable gamble with the survival of the Korean people in the balance.

That said, South Korea and the US also bear the responsibility for wasting several critical chances to keep North Korea from developing nuclear weapons. South Korea let the situation fester for 10 years, during the presidencies of Lee Myung-bak and Park Geun-hye. And the US, for its part, has repeatedly failed to prioritize the North Korean nuclear issue in its foreign policy. The moment that then US President Donald Trump walked away from his second summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un in Hanoi in 2019, following the last-minute intervention of national security advisor John Bolton, still feels awfully like a missed opportunity.

So what should we do now? We have the short-term goal of countering North Korea’s nuclear threat, and we have the long-term goal of ending North Korea’s nuclear weapons program and achieving peace and security on the Korean Peninsula.

President Yoon Suk-yeol has only shown an interest in that short-term goal. But perhaps that’s natural for a conservative president who prioritizes national security.

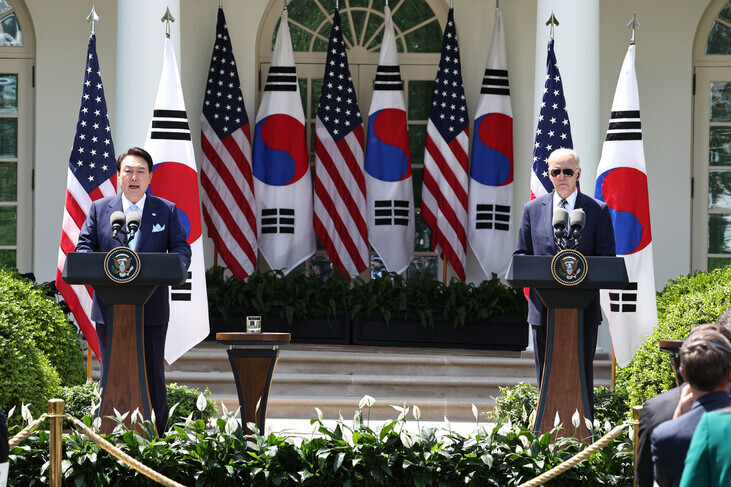

Yoon released the Washington Declaration alongside US President Joe Biden in the US in April. The central provision of the declaration was “the establishment of a new Nuclear Consultative Group (NCG) to strengthen extended deterrence, discuss nuclear and strategic planning, and manage the threat to the nonproliferation regime posed by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK).”

In fact, the Washington Declaration has made us a little safer from the threat of North Korean nuclear weapons. But the declaration contains one major logical contradiction: Its very effort to protect South Korea from the North Korean nuclear threat amounts to basically recognizing North Korea as a nuclear weapon state.

The Washington Declaration would force South Koreans to remain in the awkward position of carrying around the burden of North Korea’s nuclear weapons while putting all our trust in the US’ nuclear umbrella.

As if in recognition of that issue, South Korea and the US said at the very end of the document that they “remain steadfast in their pursuit of dialogue and diplomacy with the DPRK, without preconditions, as a means to advance the shared goal of achieving the complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula.” That sentence is pretty clearly no more than a fig leaf positioned to deflect criticism.

At this point, one is compelled to pose a fundamental question to Yoon: How on earth do you mean to resolve the North Korean nuclear issue?

As it happens, Kim Tae-hyo, the first deputy director of Korea’s National Security Office, published a 109-page paper that summarizes the Yoon administration’s strategy for foreign policy, national security, and unification.

The paper details three ways to resolve the North Korean nuclear issue: consistently pursuing denuclearization talks according to principle, acquiring momentum for carrying out North Korea’s denuclearization through Yoon’s “audacious initiative,” and working with the international community to engineer a change in North Korea’s attitude.

While I carefully perused the points made in the paper, their exact meaning escaped me. For example, “consistently pursuing denuclearization talks according to principle” is elaborated as follows:

“It is when dialogue and negotiations are based on mutual respect and trust that they can finally lead to significant results. As a consequence, the Yoon administration means to consistently pursue denuclearization negotiations according to principle. As difficult and tiring as that may be, it will ultimately be the right way to establish a framework for mutual trust and dialogue.”

That still leaves me wondering what exactly the Yoon administration intends to do.

The second point about the “audacious initiative” copies a passage from Yoon’s congratulatory address on Liberation Day (August 15) last year. And the third point about cooperation with the international community has no more substance than the previous points.

“In the event of a serious provocation such as a nuclear test, we will impose independent sanctions on North Korea in cooperation with friendly countries along with whatever new sanctions resolutions are adopted by the UN Security Council. We will use our diplomatic resources to encourage China and Russia to play a constructive role in that process.”

It’s impossible to know from this description what the UN Security Council’s new sanctions resolution against North Korea might be, what South Korea’s independent sanctions on the North might look like, or what diplomatic resources the South would use to encourage China and Russia to play a role. It’s enough to make you wonder whether Yoon and his people in the National Security Office are actually willing and able to pursue denuclearization, or whether they simply mean to hang around until North Korea falls apart.

Grand initiative with US and China neededIf you were Kim Jong-un or another senior official in North Korea, would you trust the South Korean government’s statements enough to take part in denuclearization talks?

Regardless, North Korea doesn’t regard the South as a partner for nuclear talks. The North sees its partner as being the US. Initially, the North actually seems to have considered giving up its nuclear program in exchange for diplomatic recognition and economic aid from the US. But now the North holds that it will never give up its nukes.

It\'s safe to say that North Korea’s change of heart was largely shaped by the experiences of Iraq, Libya and Ukraine. Muammar Gaddafi of Libya abandoned his nuclear program in exchange for diplomatic relations with the US, only to be gunned down by rebels backed by NATO. Ukraine was persuaded to give up its nuclear weapons by the US and Russia in the early 1990s, and now it’s on the defensive against a Russian invasion.

What that means is that North Korea completely abandoning its nuclear program would take much longer, and involve a much more complicated process, than in the past. South Korea will have to spearhead the development of an ambitious vision, detailed roadmap, and concrete action plan that can attract only North Korea but also the US, China and Korea’s other neighbors.

Let’s wrap this up. The Hankyoreh recently printed a series of articles on the 70th anniversary of the Armistice Agreement and the Korea-US alliance. The third article in the series — “Sisyphus’ Struggle for Peace on the Korean Peninsula,” by Lee Je-hun — contains the following passage.

“The last five inter-Korean summits resembled Sisyphus’ struggle, but they weren’t for nothing. They revealed that all obstacles on our journey toward peace and prosperity on the Korean Peninsula, however they may look on the surface, are rooted in the Cold War relic on the Korean Peninsula known as the armistice system. Just as Sisyphus can never give up his struggle, neither may we pause on our journey toward a peaceful and prosperous peninsula.”

When Yoon was inaugurated as South Korea’s president on May 10, he swore to strive for “the peaceful reunification of the fatherland.” I hope he’ll make a meaningful contribution to peace and the denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, just as previous presidents have.

But is he actually capable of that? What do you think?

By Seong Han-yong, senior editorial writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0517/8117159322045222.jpg) [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later

[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later![[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/7417158465908824.jpg) [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence- [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

- [Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- [Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- [Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- 2For new generation of Chinese artists, discontent is disobedience

- 3[Photo] 1,200 prospective teachers call death of teacher “social manslaughter”

- 4S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 5Xi, Putin ‘oppose acts of military intimidation’ against N. Korea by US in joint statement

- 6[Exclusive] Unearthed memo suggests Gwangju Uprising missing may have been cremated

- 7[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

- 8[Special reportage- part I] Elderly prostitution at Jongmyo Park

- 9Chun Doo-hwan arrived in Gwangju by helicopter before troops opened fire on civilians

- 10[Interview] Recalling seeing soldiers secretly burying bodies behind Gwangju Prison