hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Could Putin’s visit to North Korea resurrect a Cold War-era military alliance?

The key phrases needed to interpret the historical, strategic, and structural meanings behind Russian Vladimir Putin’s visit to Pyongyang on Tuesday and Wednesday are “nine months” and “24 years.”

Firstly, the North Korea-Russia summit is taking place nine months after Putin met North Korean leader Kim Jong-un at the Vostochny Cosmodrome in Russia’s Far East on Sept. 13, 2023. This indicates Russia’s strong intent to continue strengthening ties with North Korea as it continues its war in Ukraine.

What is even more important is the fact that Putin is to visit North Korea for the first time in 24 years. Putin last visited North Korea on July 19-20, 2000, two months after his inauguration as the president of Russia on May 7, 2000. He is the only leader of the Soviet Union or Russia to have set foot in North Korea since the founding of the USSR in 1922. To North Korea, Putin’s first visit to the country in nearly a quarter of a century will rightly be deemed historic.

The outcome of Putin’s summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un will come down to how this first summit in nine months will devise a response to international affairs as well as the historical and strategic milestones latent in Putin’s first visit to Pyongyang in 24 years. Whatever the outcome is, it is bound to have profound implications for the future of North Korea-Russia relations, as well as the situation in Northeast Asia and global international politics.

Redefining of North Korea-Russia relations

The biggest focus is how Kim and Putin will redefine their bilateral relations. Namely, many watchers are keen to see if they will amend their Treaty of Friendship, Good-Neighborliness, and Cooperation signed on Feb. 19, 2000, and if so, how.

A press release published in the Rodong Sinmun newspaper immediately after Minister of Foreign Affairs Choe Son-hui’s official visit to Russia in January stated that a “satisfactory agreement” had been reached in the discussion on putting the two sides’ relations on a “new legal basis.”

This opens up the possibility of a revision to the treaty, which acts as the basic legal document governing North Korea and Russia’s bilateral relations.

There is much speculation as to whether the relations will be elevated to the level of a “strategic cooperative partnership” like the relationship shared by South Korea and Russia, or whether it will reinstate the Cold War alliance by bringing back a clause stipulating immediate military intervention in the event of an armed attack by outside forces.

The Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance adopted on July 6, 1961, by the Soviet Union and North Korea stipulated that “should either of the contracting parties suffer armed attack by any state or coalition of status and thus find itself in a state of war, the other contracting party shall immediately extend military and other assistance with all the means at its disposal” — an indirect reference to the Soviet nuclear umbrella — but these ideas are missing from the current treaty, as the treaty expired in 1996 after the two sides failed to extend it over a disagreement over whether the clause should be retained.

The full text of the new treaty is not publicly available, but the joint declaration that was issued during Putin’s visit to North Korea in July 2000 — five months after the adoption of the new treaty — stated that in Article 2 of the treaty, the two sides vowed to “get in touch with each other without delay” in the event of aggression or when there is the need to have consultations and cooperate with each other. What was once a pledge to “immediately extend military and other assistance” had been softened to become a “willingness to get in touch.”

However, South Korean national security adviser Chang Ho-jin announced during a television interview on Sunday that Seoul had reached out to Moscow to send a cautionary message that Russia should not “cross any lines.” The comment coincided with remarks by a high-ranking government official, who said that there “seems to be talk of a treaty similar to an alliance.” This suggested that it was likely that the treaty might be amended to contain a provision stipulating automatic military involvement in the event of an outside attack.

At the same time, many former high-ranking South Korean government officials and experts believe that it is unlikely that a revision of the bilateral treaty to include such language will come to pass, as it is not in line with Russia’s foundation for foreign policy or its national interest.

On June 5, when Putin met with the heads of international news agencies ahead of the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, he stated, “We see that there is no Russophobic attitude in the work of the South Korean leadership,” and emphasized his interest in developing bilateral ties with the whole of the Korean Peninsula. Such remarks can be read to mean that he wishes to develop bilateral relationships with not only North Korea, but South Korea as well.

Some believe that, despite the concerns coming out from the Yoon Suk-yeol administration, North Korea itself isn’t looking to bring back any promises for military intervention in a revised treaty.

“The reinstatement of the automatic military involvement provision means that the North Korean military would be subordinated to Russia. That is hardly an option for Kim Jong-un, who has been declaring to his people that strengthening the country’s nuclear arsenal is the best way of deterring war,” assessed Chang Yong-seok, a visiting scholar at the Institute for Peace and Unification Studies at Seoul National University who also served as the assistant director of North Korea-related intelligence analysis at the National Intelligence Service.

Expanding cooperation

Since their summit in September of last year, North Korea and Russia have discussed mutual cooperation through mutual visits by high-ranking officials in the fields of economics, legislation, foreign affairs, party affairs, local governments, agriculture, culture, education, health, forestry and logging, youth affairs and intelligence. Putin’s visit to North Korea may result in formal agreements that span various sectors.

Above all else, military cooperation has always been the hot potato when it comes to affairs between North Korea, South Korea and Russia. Military cooperation between Moscow and Pyongyang would not only violate the UN Security Council’s sanctions against North Korea, but unavoidably damage relations between Moscow and Seoul. However, Russia providing offensive weaponry or cutting-edge technology related to nuclear weapons and missiles would be crossing a red line. Experts therefore think the likelihood of that occurring is low.

“Even back in the Soviet days, Russia never provided cutting-edge strategic military technology or weapons to North Korea,” said a high-ranking official in foreign affairs and national security.

During a television appearance on April 27, national security adviser Chang Ho-jin used the phrase “balance of concerns” to express the mutual awareness of which red lines to not cross when it comes to South Korea-Russia relations.

This makes economic cooperation much more likely. An example of a mutually beneficial agreement would be Russia providing natural gas and crude oil to an energy-starved North Korea while North Korea provides much-needed labor for development projects in the Russian Far East. Although both ends of such a deal are still in violation of UN sanctions, there is a high chance that Pyongyang and Moscow could find a way around them.

Since their September summit last year, Russia has sent a delegation from Primorsky Krai to visit North Korea twice (in December 2023 and March 2024), while a North Korean delegation from the city of Rason visited Primorsky Krai from May 12 to 18 this year.

What about the denuclearization issue?

During his September summit with Kim Jong-un, Putin did not mention denuclearization a single time, nor did he specifically condone Pyongyang’s nuclear program. During an interview with a Russian media outlet on March 13, ahead of the Russian presidential election, Putin was asked whether he’d consider bringing North Korea under Russia’s nuclear umbrella. Putin responded that North Korea “has its own umbrella” and that the country “didn’t ask us for anything.”

The interview was followed by various analysts saying that Putin had officially recognized North Korea as a nuclear state for the first time, but it can also be read in another way: as an acknowledgment that Russia has no intention to bring North Korea under its nuclear umbrella.

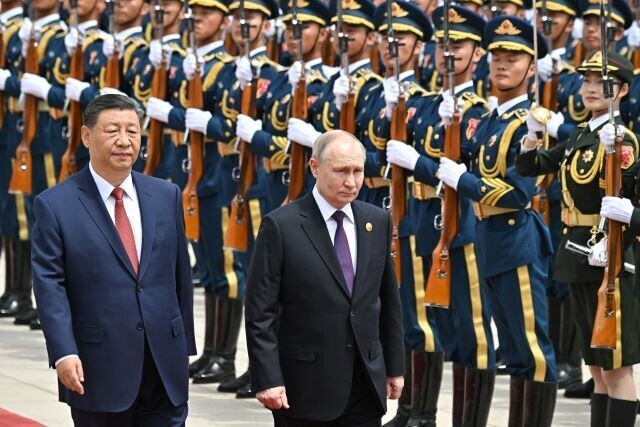

Putin did offer an official position on North Korea's nuclear weapons in a joint statement released after his summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping on May 16. The statement included a line in which the two leaders noted that they “oppose the acts of military intimidation by the US and its allies that escalate confrontation with North Korea.” The statement also called for “the resumption of negotiations regarding North Korea and affiliated countries.” In short, Russia’s president called for a “resumption of negotiations” regarding North Korea’s nuclear capacity at a time when Kim Jong-un declared there would be no negotiations on the matter.

“Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula has consistently been the end goal for Russian authorities,” said an anonymous source familiar with foreign affairs.

“Russia always reminds the outside world that Moscow’s measures to strengthen its partnership with North Korea are not an endorsement of Pyongyang’s nuclear program,” the source added.

It therefore remains to be seen whether Putin and Kim will publicly address the nuclear issue during Putin’s visit.

Trilateral cooperation along the Tuman?

Observers are also keen to see if Kim and Putin will discuss concrete measures for trilateral cooperation involving China. During their summit in May, Putin and Xi announced that they had agreed to hold “constructive discussions” with North Korea on granting Chinese ships access to the lower Tuman River.

China and North Korea share a border of 1,334 kilometers (829 miles) that spans both the Amnok River (Yalu River) and the Tuman River (Tumen), the latter emptying into the East Sea. Legal jurisdiction over the lower Tuman, which leads to the ocean, belongs to Russia and North Korea, but not China. That’s because the lower Tuman forms the North Korean-Russian border.

The Convention of Peking in 1860 forced Qing China to cede territory (around 600,000 square kilometers) in Manchuria now known as Primorsky Krai to the Russian Empire. Since then, China has longed for direct access to the Pacific, but a lack of consensus between Russia and North Korea has been the main obstacle. This is why observers are so focused on whether Putin’s visit to North Korea will lead to trilateral cooperation with China, which would likely take the form of a trilateral agreement on the lower Tuman.

Yet there are reasons Putin and Kim would not want to accelerate such a process. On Jan. 1, Kim announced 2024 to be the “year of DPRK-China friendship” to celebrate 75 years of diplomatic relations, but Pyongyang-Beijing relations have recently not been smooth sailing. North Korea denounced the joint statement released on May 27 following the trilateral summit between South Korea, Japan and China held in Seoul, with Pyongyang’s Foreign Ministry saying the statement represented a “wanton interference” in its internal affairs. This is likely why China scheduled a meeting between foreign affairs and national security officials at the vice-minister level with South Korea, which will be held in Seoul at the time of Putin’s visit to Pyongyang.

What is Putin’s play?

Putin’s visit to North Korea was preceded by visits to Belarus (May 23-24) and Uzbekistan (May 26-28), and will be followed by a visit to Vietnam (June 19-20). This may be an indication that amid a swing in the balance of power between China and Russia toward Beijing’s favor, Putin is seeking to swing it back toward Moscow. Many analysts think Putin is trying to secure strategic breathing room in East Asia and the Indo-Pacific. It is therefore too early to assume that trilateral partnership between Pyongyang, Beijing and Moscow is a done deal.

By Lee Je-hun, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem [Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0626/5517193887628759.jpg) [Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

[Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem![[Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0625/9617193034806503.jpg) [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

[Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order- [Editorial] Workplace hazards can be prevented — why weren’t they this time?

- [Editorial] Seoul failed to use diplomacy with Moscow — now it’s resorting to threats

- [Column] Balloons, drones, wiretapping… Yongsan’s got it all!

- [Editorial] It’s time for us all to rethink our approach to North Korea

- [Column] Why empty gestures matter more than ever

- [Editorial] Seoul’s part in N. Korea, Russia upgrading ties to a ‘strategic partnership’

- [Column] The tragedy of Korea’s perpetually self-sabotaging diplomacy with Japan

- [Column] Moon Jae-in’s defense doublethink

Most viewed articles

- 1Dispatched into unknown danger, foreign day laborers were defenseless against blaze

- 2Three expert views of the war in Gaza: From a Hamas official to Israel’s ambassador in Seoul

- 3CIA record confirms US ‘completely destroyed’ Seoul’s Haebangchon in 1950 bombardment

- 4Blaze at lithium battery plant in Korea leaves over 20 dead

- 5[Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- 6[Editorial] Workplace hazards can be prevented — why weren’t they this time?

- 7How 17 km of river could be a fertile bed for NK-China-Russia cooperation

- 8North Korea, Russia are going backward into history, Yoon says of new defense pact

- 9[Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

- 10Russia says new treaty with North Korea isn’t directed at South