hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] Super ecological environment of DMZ an unexpected “gift” of division

Cutting across the midsection of the Korean Peninsula, the DMZ is a tragic setting created by war and division – but in natural terms, it is a land of blessings.

While South and North Korea have remained at odds across heavy barbed-wire fences for the 66 years since their division, the national environment, untouched by human hands, has transformed the world’s most forbidding region of heavy militarization into a space of peace and life.

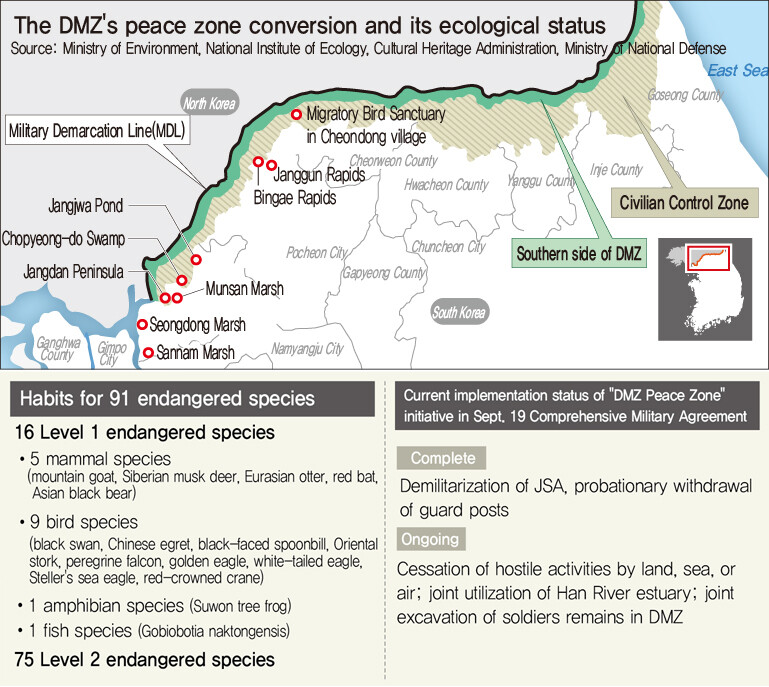

The DMZ’s ecological axis, which stretches for 248km from Paju, Gyeonggi Province, to Goseong, Gangwon Province, is divided into a western section (Paju and Yeoncheon) with broad hills, rivers, farmland, and wetlands; a mountainous east (Hwacheon, Yanggu, Inje, and Goseong); and a central portion (Cheorwon) that serves as an ecological corridor.

Boasting ecosystems that span mountains, wetlands, rivers, and plains, the DMZ is a paradise for flora and fauna: representing just 1.6% of South Korea’s total area, it has 4,873 species (20%) of wildlife, including 91 that are endangered (41%).

The central and western regions in particular, with their richly developed wetlands and farmlands – the Imjin and Sacheon Rivers, Sami Stream, the Hantan River, Yeokgok Stream, and the Cheorwon Plain – have drawn international attention as the most stable habitats for the red-crowned and white-naped cranes, which are protected species internationally.

The heavily forested eastern DMZ area is also home to endangered wildlife including the Asian black bear, long-tailed goral, Siberian musk deer, leopard cat, Eurasian otter, yellow-throated marten, and Siberian flying squirrel.

The superior ecological environment in the DMZ is an unexpected “gift” of division. But with recent signs of reconciliation between South and North, the ecosystem – and the lives of local residents – are under threat amid widespread plans for development, including the withdrawal of the Civilian Control Line (CCL) and building of roads.

The Imjin River and rice paddies are the core elements of the ecosystem in the western DMZ. Many wetlands have been formed from the rising and ebb tides of the Imjin and Han Rivers’ open estuaries, including those at Sannam, Gongneung Stream Estuary, Seongdong Village, Jangdan, Munsan, Imjingak, and Chopyeong Island. With their associated rice paddies, bogs, and natural streams, the wetlands form habitats for wildlife.

Midday surveys conducted once a week by the Paju branch of the Korea Federation for Environmental Movements (KFEM) found a total 47 endangered species in the basin of the Imjin River estuary, including birds, insects, fish, mammals, amphibians, and reptiles.

From the Imjin River estuary past Sami Stream and on to Yeokgok Stream in Cheorwon, the DMZ includes broad swaths of land that were once paddies but have since transformed into natural wetlands. The natural wetlands connect with the paddies and the waterway of the Imjin, which is preserved in its natural river state.

The paddies around the Imjin and CCL in particular are important wetlands used for food, nesting, and rest by endangered bird species including the red-crowned and white-naped crane, black-faced spoonbill, white-tailed eagle, watercock, and bean goose. The paddies are also habitats for the endangered Suwon tree frog and Seoul frog, as well as the leopard cat, Amur rat snake, boreal digging frog, giant water bug, and diving beetle.

But the government is now pushing policies to reduce rice paddies, citing the high volume of rice production. And with paddies classified as “Level 3” according to the ecology and natural map (a map listing natural environments according to their ecological value), large areas of farmland in Cheorwon and Paju are facing development pressures.

For that reason, KFEM joined farmer and environmental groups in the Paju, Yeoncheon, and Cheorwon areas in submitting a policy proposal to the government last month for the preservation of paddy wetlands within the CCL, with the initial aim of having state- and public-owned farmland within the CCL designed as a wetland protection region. As target sites for protection, they listed the river farmland in the village of Majeong, Samok, and Geogok along the Imjin in Paju; farmland and reed wetlands on the Jangdan Peninsula in Paju; upper river sites at the Imjin’s Gunnam Flood Control Reservoir in Yeoncheon; and areas of the Cheorwon Plain where landmines are current buried. Additionally, KFEM also proposed the earmarking of a budget for purchasing of land belonging to absentee landlords, expansion of support measures for farmer-owned land, abolition of the rotation support system for field crops, increased budget monies and targets for biodiversity management contracts, and a ban on the use of cement for agricultural waterways.

The Ministry of Environment has been administering the Han River estuary in Gimpo, Goyang, and Paju as a wetland protection zone since its designation in 2006. But the Imjin River estuary is not included in the protection area.

On the afternoon of Sept. 30, dozens of geese – the “heralds of winter” – flocked through the skies over the Imjin River basin at Samgot Village in Yeoncheon’s Jung Township. An 850,000-square meter flood plain in front of the village – where rice was farmed as recently as five to six years ago – was overgrown with bur-cucumber, giant ragweed, and other harmful plants thanks to a ban on farming imposed by the Korea Water Resources Corporation (K-water) after construction of Gunnam Dam.

On Sept. 17, 32 white-naped cranes visited a field in Gangsan, a village in the Dongsong township of Cheorwon, where the harvest comes earlier than in Paju or Yeoncheon. Some 17,000 geese also arrived in Cheorwon.

Typically remaining on the Korean Peninsula from late October to March, cranes mostly spend their winters in the DMZ area around Cheorwon and Yeoncheon. In February 2018, a total of 374 red-crowned cranes, 387 white-naped cranes, and two Siberian cranes were observed in Yeoncheon. A survey in January 2019 observed a total of 5,492 red-crowned and white-naped cranes in Cheorwon.

With the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) estimating the population of cranes living in the wild this year at 1,830, the number means that over half of them winter at the DMZ in South Korea.

The reason Cheorwon has become the world’s biggest wintering site for cranes is thanks to its good environment, with over half of rice paddies – more than 10,000 hectares – falling within the CCL. Other factors include the pond-like “saemtong” springs found throughout its fields – a unique feature of the Cheorwon ecosystem – and the secure feeding and sleeping sites for cranes with the Hantan River, Yeokgok and Daegyo Streams, and Togyo Reservoir.

But residents have recently become very concerned about major threats to the crane habitats due to lifting of CCL status and rampant development. Known as the “village of migratory birds,” Yangji in Dongsong Township has become an inhospitable environment for cranes with the arrival of stables following the removal of its CCL status in 2012. In the three years between 2016 and 2018, a total of 78 commercial stables measuring 180,000m2 in area have taken up residence in Cheorwon County.

The proliferation of solar power structures in the places vacated by military units has also prompted objections from residents, who have criticized it as “rampant development that shows no consideration for regional characteristics.” Over 400 solar power projects have recently been granted permits in Cheorwon.

“In the three years since the CCL status was lifted and the stables and solar power structures started coming in, not only cranes but other animals you used to see all the time, including leopard cats, digging frogs, and toads, have all but disappeared,” said Choi Jong-soo, president of the group People Who Farm with the Cranes.

“Once the CCL is lifted, there is no stopping development. The government needs to establish land ahead of time so that the farmers and cranes can live together,” Choi insisted.

The Yeoncheon area is also considered a natural crane habitat with its rapids along the Imjin River’s upper course and the abundance of wetlands and Job’s tears fields (a feeding site) in the DMZ area. The Janggun rapids are an optimal sleeping place for the birds, with an island in the middle of the Imjin River that allows them to avoid predators. Around 500m upriver from the Janggun rapids are the Bingae rapids – shallow waters (20–30cm) that do not freeze in the winter, allowing the cranes to catch fish and marsh snails.

But the environment for cranes was worsened, with the Janggun rapids submerged by enforced winter ponding at Gunnam Dam, which was built by K-water as a flood control reservoir. To make matters worse, plans to move a CCL checkpoint at Samgot 3km north to the village of Hoengsan within the year spell crisis for the protection of crane habitats.

“If the checkpoint is relocated without any protection measures, the Janggun and Bingae rapids areas where the cranes sleep will be exposed to motor vehicles and crowds of people,” warned Lee Seok-woo, co-president the Yeoncheon Imjin River Civilian Network.

An official with Yeoncheon County said, “We are considering plans for keeping the current Samgot Village checkpoint in place to control nighttime access even if the checkpoint is relocated for visitor convenience.”

Amid the recent climate of inter-Korean reconciliation, development plans for the DMZ region have been proliferation, including efforts to promote “ecosystems, peace, and tourism,” development of a “DMZ ecology, culture, and tourism belt,” and a project to link and modernize South and North Korean railways and roads. The Ministry of the Interior and Safety (MOIS) is preparing to invest a total of 13.2 trillion won (US$11.07 billion) through 2030 in a comprehensive development plan for the border region.

Many worry these development plans could deal a further flow to the environment at a time when endangered species habitats and resident lives are already under threat in some regions due to tourism resource development, road construction, and the building of vinyl greenhouses and stables. Speaking at the DMZ Forum held on Sept. 19 by Gyeonggi Province, Kim Choong-gi, director of the natural environment research office at the Korea Environment Institute (KEI), stressed, “Once an ecosystem becomes damaged, it takes anywhere from decades to centuries for it to be restored.”

“We cannot allow any usage or development that destroys the primeval ecosystem, even if it is dressed up with terms like ‘life’ and ‘peace,’” Kim said.

Residents are objecting in particular to the Munsan-Mt. Dora expressway currently being pursued by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, with a design that has it cutting across the Jangdan Peninsula and fields in Baegyeon and other villages. The Jangdan Peninsula is considered a likely site for a “special unified economy district,” as listed among the Moon Jae-in administration’s 100 governance tasks, as well as a “second Kaesong Industrial Complex,” which has been mentioned in numerous election pledges. Environment groups have objected to the development, citing the peninsula’s role as a retention site to prevent flooding in the Munsan area, a production side for eco-friendly rice for use in school meals, and a habitat for endangered flora and fauna.

“For preservation of the DMZ to hold meaning, it needs to be connected to the Civilian Control Zone rather than applying to a narrow four-kilometer strip of land,” said Noh Hyun-ki, co-chairperson of KFEM’s Paju branch.

“What in the Civilian Control Zone urgently needs now is not development but ecological surveys and surveys and a cultural heritage surface survey,” Noh said.

By Park Kyung-man, North Gyeonggi correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol![[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/7317139454662664.jpg) [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 2Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 3N. Korean hackers breached 10 defense contractors in South for months, police say

- 4[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 5Up-and-coming Indonesian group StarBe spills what it learned during K-pop training in Seoul

- 6[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 7Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 8Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 9Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 10Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan