hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Guest essay] Yoon jumped on US bandwagon at NATO summit - why doing so isn’t in Korea’s interest

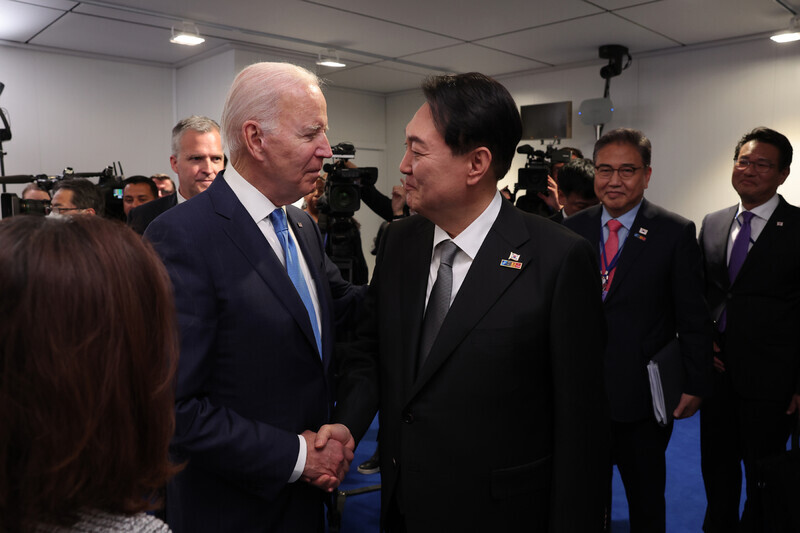

Editor’s note: On May 21, President Yoon Suk-yeol held a bilateral summit with US President Joe Biden and announced Korea would be taking part in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), a US-led economic security initiative. Yoon then went on to attend the NATO summit in Madrid, Spain, on June 29.

In other words, less than two months after its inauguration, the Yoon administration has made clear its foreign policy choice to side with the US and the West.

To better understand this move by Yoon and what approaches it will require going forward, the Hankyoreh is running the following essay by Handong Global University professor Kim Joon-hyung, who formerly served as chancellor of the National Diplomatic Academy.

By Kim Joon-hyung, professor at Handong Global University

Yoon’s supporters all applauded the president’s attendance at the NATO summit. According to them, the new South Korean president successfully made his international debut and raised his status by displaying his presence by standing shoulder to shoulder with the leaders of major world powers.

In particular, supporters highly praised the president’s decision to diplomatically side with the West and abandon the perceived indecisiveness of the previous administration, which had maintained ambiguity between the US and China.

The domestic media seemed to treat Yoon’s NATO attendance in the same light as President Moon Jae-in’s participation in the G7 summit last year.

However, NATO is fundamentally different from the G7 and G20 summits as it is a military and security alliance. To be invited to a gathering of NATO is indeed unlike being invited to a European Union meeting, though many of the member nations may overlap.

If this decision were to have come as an attempt to use the NATO summit as a stand-in for an invitation to the G7 summit that never arrived, that would indeed be very amateurish. If this wasn’t the case and the government’s decision was made after conducting a cost-benefit analysis, the situation becomes even more problematic since it means the government chose unilateral bandwagon diplomacy on purpose — a decision that could cause enormous difficulties for Korea’s position in the future.

Here, it is important to note that NATO has solidified its path as an anti-China, anti-Russian counter alliance by adopting a new strategic concept for the first time in over a decade. In this latest concept, NATO characterized Russia as a “direct threat” and China as a “systemic challenge.”

These classifications are a little less extreme than the original prediction that Russia would be defined as an “enemy” and China as a “threat.”

Still, one can see that Germany and France’s positions of trying to avoid excessive confrontation with China due to economic relations were partially recognized by other NATO members.

The US has insisted that the reason for NATO’s continued existence, despite the end of the Cold War, is for the sake of the common security of Europe as a whole. However, this essentially means that the revival of the Cold War system is now a fait accompli.

It is clear that the US intends to unite Europe in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and link the alliance with issues tied to Russia and China. As such, it is rather unreasonable to argue that we are not targeting any particular country by participating in the NATO summit.

Moreover, participation in the summit by the likes of Japan, Australia and New Zealand has helped the US’ attempt to link the European and Asian alliances.

The trilateral talks held on the sidelines of the NATO summit between Korea, the US and Japan — which the White House hailed as “historic,” despite its 25-minute duration — clearly revealed the US’ ever-present determination to contain China through trilateral cooperation.

Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida mentioned strengthening Japan’s defense forces, which brings up the possibility of rearmament. Meanwhile, President Yoon saw the trilateral summit with the US and Japan as the most meaningful agenda item and cited the fact that he agreed on the principle of resuming “military security cooperation” with the US and Japan as a great achievement.

South Korea, the US and Japan had previously limited cooperation to specific issues, such as North Korea’s nuclear program, but this new development suggests that they may move toward a military alliance in the future if the president’s phraseology of “military and security cooperation” is accurate.

If Korea joins an alliance with Japan, which is desperate to rearm itself through a geopolitical crisis without reflecting on the past, then it could open the door for the Japanese Self-Defense Force to land on the Korean Peninsula in case of an armed conflict here, or for the South Korean military to intervene in potential Russo-Japanese or Sino-Japanese conflicts. The results of such interventions could lead to unimaginably terrible consequences for Korea.

It is clear to see that the Yoon administration has chosen to base its foreign policy on bandwagoning amid the global bloc divide.

The previous government’s direction was criticized for balance or strategic ambiguity, but this was due to its difficult structural limitations. If it was easy to choose a side and if it was in the national interest to do so, of course the previous government would have made that choice. There is no way that any progressive administration in the past was unaware that Korea cannot survive by ditching the pro-US line.

Therefore, any real “balance” between the US and China was impossible from the beginning for Korea. In the midst of strategic competition, Korea tried to avoid a new Cold War conflict and make its own gains despite the unstable geopolitical environment, but instead, we only ended up putting a political frame on the situation.

The problem starts now, and the inconveniences will begin in earnest. Time magazine warned that South Korea’s participation in the NATO summit would push back relations with Russia and China.

The Chinese government sees the latest NATO summit as a revival of the Cold War system, but it has not yet engaged in a direct confrontation with Korea.

However, if South Korea takes the lead in this confrontation between the two major global blocs, the story will be different. There is no doubt that the South Korea-US alliance is our most important diplomatic asset, but we must keep in mind that the current administration’s overly pro-US and Western piggybacking strategy can narrow our position and make us lose our diplomatic leverage.

In this era, unilateral diplomacy cannot properly protect the national interest. Even American intellectuals advise the Biden government that it is more advantageous to maintain friendly relations between Korea and China than to make South Korea overly dependent on the US.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 3After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 4[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 5[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 6Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 7[Photo] Smile ambassador, you’re on camera

- 8All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 9[Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- 10US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters