hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] America must frankly own up to role in tragic Jeju April 3 Incident

South Koreans were long forced to remain silent about the tragic Jeju April 3 Incident.

Over 30,000 residents of Jeju Island were killed by the police, the military and paramilitary groups such as the Northwest Youth Association during the incident, which began with a crackdown on a celebration of the March 1st Movement in 1947, continued with an uprising on April 3, 1948, and finally concluded on Sept. 21, 1954.

But under Korea’s authoritarian governments, the uprising was stigmatized as a communist revolt, and the relatives of the victims were forced to live with their despair, shackled by a system of guilt by association.

It was not until after Korea’s democratization in 1987 that the incident could be debated publicly. A campaign to uncover the truth of those events was launched under the administration of Kim Dae-jung, and the perpetrators and victims found reconciliation as well.

South Korea’s National Assembly revised the Special Act on Discovering the Truth of the Jeju 4.3 Incident and the Restoration of Honor of Victims, settling the issue of compensation for the victims. This modeled “truth and reconciliation” on a level unprecedented around the world.

But for the people of Jeju, one issue remains unresolved — identifying the US’ role and responsibility and asking for the appropriate measures.

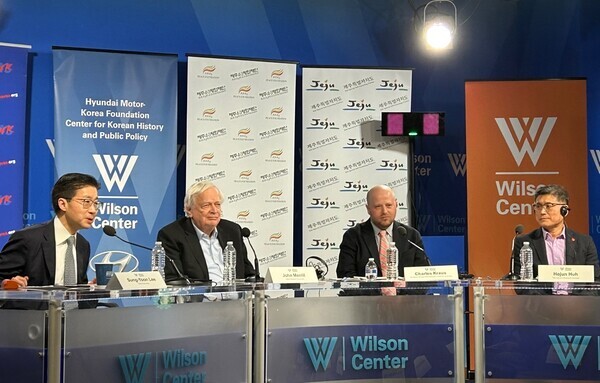

That issue was addressed directly in a symposium titled “US-Korea Relations: Retrospective on the Jeju April 3 Incident, Human Rights and Alliance,” which was organized by the Wilson Center, a bipartisan think tank in Washington, and Director Sue Mi Terry of its Asia Program on Dec. 8.

This was a highly unusual agenda given the typical conventions of Washington think tanks. It would be difficult to explain if not for confidence in the maturity of the Korea-US alliance.

During the symposium, representatives of the victims’ families and the Jeju 4.3 Peace Foundation provided a vivid account of the tragic events that occurred on Jeju Island.

Huh Ho-jun, a Hankyoreh reporter who has long specialized on the topic, quoted American government sources to argue that the US military government had operational jurisdiction over the South Korean military and police and condoned scorched-earth operations against the Jeju people. In short, he provided convincing evidence for American responsibility.

What’s notable is how American participants at the symposium responded.

John Merrill, former chief of the Northeast Asia Division of the Bureau of Intelligence and Research at the US Department of State and the first person in the US to focus on the Jeju April 3 Incident, described American involvement in the incident as an objective fact and argued that the US ought to make a statement about it.

Kathleen Stephens, the former US ambassador to Korea who is a centrist, recommended that the issue should continue to be addressed. Painful as it may be, she said, it’s time for the US to squarely face the painful truth about the bloody Jeju April 3 Incident.

Tufts University professor Lee Sung-yoon, regarded as a conservative, also argued that the US government ought to express its regrets about the tragic events that occurred in the Jeju April 3 Incident. Such a statement, Lee said, would benefit the alliance of two countries that share the values of democracy, peace, freedom and justice.

However, there were minor differences in the specific approaches suggested.

Frank Jannuzi, president of the Mansfield Foundation, said that rather than making an explicit apology for the Jeju April 3 Incident, it would be better for the US president to hold a summit with Korea on the island and use the occasion to pay a memorial visit to the Jeju 4.3 Peace Park.

Others spoke of the need for aggressive public diplomacy with Congress and for a campaign to gradually bring the issue to people’s attention through the US media, education and public relations.

It’s significant that, despite the concerns of some in South Korea, a consensus is forming that a bold decision to revisit the issue of American responsibility for the Jeju April 3 Incident and overcome this thorny history through an American apology would help strengthen the Korea-US alliance.

It’s also notable that American figures voiced wide-ranging agreement regardless of their policy line. To be sure, these opinions are unlikely to lead to an immediate change in the US government’s official stance. But in effect, they have set the stage for a perceptual shift that demonstrates the responsibility of a mature alliance.

The participants in the symposium were in agreement that we must not allow something as tragic as the Jeju April 3 Incident to be repeated. That also has major implications for the future of the Korea-US alliance.

In essence, an alliance is a pragmatic measure, an arrangement for military cooperation against common threats and enemies.

Therefore, an alliance’s primary purpose is to seek strategic stability through the balance of power, while also exercising a collective veto or deterrence to prevent real or potential military adventurism by enemy states.

The goal of an alliance is to deter war and, if deterrence fails, to guarantee victory. Viewing a popular uprising on Jeju as a communist rebellion and condoning a barbaric suppression of that uprising when the lines of the Cold War were being drawn can be seen as an extension of that kind of logic.

While this may sound paradoxical, the Korea-US alliance should now establish itself as an alliance for peace. More than simply preparing for war in the interest of national security, it should use diplomacy to build peace and prevent the sacrifice of innocent lives.

Surely an alliance of that sort would conform to the most universal values shared by Korea and the US. That’s also the painful lesson of the Jeju April 3 Incident.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 3[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 4Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 5Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 6No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 7S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 8The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 9[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 10Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?