hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Guest essay] How Korea must answer for its crimes in Vietnam

By Lim Jae-sung, legal representative of Nguyễn Thị Thanh in state compensation case

“I want the Korean government and veterans of the war [in Vietnam] to own up to the facts and to ease the pain of the victims of those incidents and their family members. I’ve been in so much pain ever since the age of eight, and my injuries still ache to this day. It’s indelible. I want a judgment to be made according to the facts. I’ve come here from Vietnam. The things that I say are true and not a lie. Your Honor, please help me.”

Those were the final remarks that Nguyễn Thị Thanh, 63, made during her appearance at a South Korean court on Aug. 9, 2022.

Born in 1960, Nguyen was shot in the abdomen on Feb. 12, 1968, by South Korean soldiers who were searching her village, called Phong Nhị, in the central Vietnamese province of Quảng Nam.

She was severely injured by the bullet, and her guts spilled out of the wound. But she managed to survive with the help of American troops who entered the village to rescue the victims shortly after the Korean troops had departed.

In short, Nguyễn had been snatched out of the jaws of death. But her mother, aunt, older sister, and other family members had been killed by Korean soldiers in the massacre.

That 8-year-old girl wasn’t able to leave the hospital for close to 10 months. And after being discharged, she still faced the struggles of being a war orphan.

Even now, Nguyễn resents that she couldn’t go to school as a child. She felt so lonely that she would pray to her dead mother at night and beg her to come to get her.

In the early 2000s, Koreans began visiting her village to express their remorse. She would show them the wound on her abdomen — running more than the span of two hands –— while sharing the things she’d suffered in 1968.

In 2015, Nguyễn became the first victim of civilian massacres during the Vietnam War to visit Korea. Vietnam War veterans demonstrated outside of the venue where she was supposed to make an address, shouting “Viet Cong!” While she still shuddered at the memory of the massacre, she stood strong and gave her testimony.

In 2020, Nguyễn Thị Thanh sued the Korean government, asking it to take responsibility for the massacre. The verdict was delivered on Feb. 7 — a total victory for Nguyễn.

In its ruling, the court accepted evidence for all the illegal actions that Korean troops perpetrated against unarmed civilians and rejected the Korean government’s argument that the statute of limitations had expired, describing that as an abuse of rights. This is the first time an official Korean organ has acknowledged the civilian massacres.

After hearing the news about her victory, the woman who had told the painful truth in a Korean court said, “It makes me so glad that the souls of the massacred people should be able to rest in peace now. I’m happy now.”

The time has come for Korea, as the aggressor here, to make a choice. Some would advise that we wait until all appeals have been exhausted, insisting that we needn’t worry about the lawsuit of a single victim.

But others feel ashamed that the Korean government didn’t do anything in the 20 years after the issue was made public until the judicial branch recognized the war crime. Those people would say that it’s time for politics and policy because this issue should not, and indeed cannot, be ignored any longer.

It's a choice between irresponsibly ignoring the court’s decision and making a prudent response.

The issue of civilian massacres in the Vietnam War has currently entered its third phase.

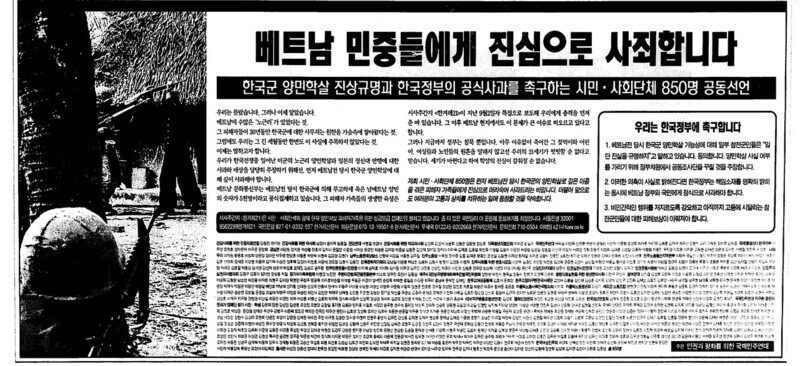

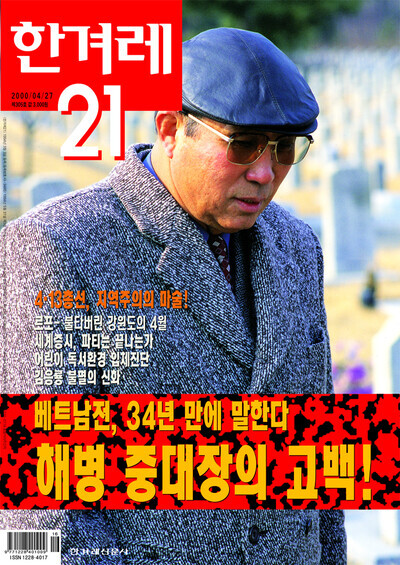

The first phase was triggered when the weekly magazine Hankyoreh 21 published an article titled “Ah, the Growing Horror of the Korean Military” in 1999 that contained the vivid testimony of the victims.

In the fertile ground of a new democracy, Korean society responded to that testimony. The “I’m Sorry, Vietnam” campaign was begun, civic groups gathered together, and the private sector took steps to learn the truth about the massacres.

While the issue had been made public, that didn’t lead to institutional changes. Articles and statements at the time ended with a similar appeal: “The government needs to take action now.” But the Korean government refused to act.

Furthermore, civic society lacked the ability to keep the issue in the spotlight. The civilian massacres during the Vietnam War became a “familiar tragedy,” and Koreans forgot about the violence.

Speaking about Korean society’s response to the massacres, sociologist Yoon Chung-ro categorized the period before 1999 as “the time of forgotten violence” and the mid-2000s and beyond as “the time of perpetrating the violence of forgetting.”

The second phase began with the first visit by a victim to South Korea in 2015.

Korean society’s capabilities and interest in the issue were so inadequate that no victim made it to Korea until 15 years after the issue was brought to the public’s attention.

But when the victims and survivors of the massacres traveled the country to give their testimony, something began to change. While the social response was not as great as during the first phase, jurists, scholars, and other professionals started digging into the issue. This was also when the Korea-Vietnam Peace Foundation, an organization that specializes in this issue, was established.

The crux of the second phase was that the Vietnamese victims took ownership of the issue by knocking on institutional and procedural doors inside South Korea and received support from Korea’s civil society in the process.

In 2019, 103 of the victims sent a petition to the Blue House asking that it investigate what happened and acknowledge the facts, officially apologize, and take measures to redress the damage. Then in 2020, the victims filed a damages lawsuit against the state, and in 2022, they petitioned the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to carry out a fact-finding investigation.

The Korean government also carried out a review of this issue. Few may be aware, but in October 2018, the Presidential Commission on Policy Planning submitted to the Blue House a document it had prepared titled “A Proposal for Establishing a Body to Investigate the Facts about Instances of Civilians Being Harmed by the Korean Military during the Vietnam War.”

“The Korean government cannot dodge criticism for having failed to take any measures whatsoever for nearly 20 years,” the document said. “The lack of any investigation at the government level will present future administrations with a serious problem when they review related positions or policies.”

That standpoint informed the document’s proposal that a fact-finding body be set up to operate under the Ministry of National Defense.

But after consulting the opinions of related organs including the Defense Ministry and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Blue House opted not to continue the discussion. The Foreign Ministry reportedly was strongly opposed to any action, and the Blue House itself was not particularly motivated.

In September 2019, the final position of the Moon Jae-in administration was announced in the Defense Ministry’s response to a petition by the victims: “While we have reviewed related materials, we did not confirm the civilian massacres claimed by the petitioners, nor can we carry out a fact-finding investigation.”

In effect, the official position of the Moon administration after 20 years of public debate about civilian massacres during the Vietnam War was that the massacres hadn’t happened and that the issue would not be investigated — this, despite the administration’s vigor in pursuing other historical issues.

The third phase has now begun with the court’s ruling in favor of Nguyễn Thị Thanh. The Defense Ministry said it couldn’t confirm the massacres, but the court nevertheless ruled that they occurred.

What is the Korean government’s opinion about this ruling? In this phase, the issue can no longer be avoided or ignored.

So what is to be done? The first priority must be carrying out an official investigation to determine the facts. That step must be taken before the government can offer an opinion and take any further steps, such as making an apology or reparations.

But no preparations have been made, and no review has been carried out. That is a level of irresponsibility that does not even serve the “national interest” spoken of by conservatives.

A gradual approach is needed for an official investigation. Under ordinary circumstances, Korea could carry out a joint investigation with the government of Vietnam, being the victim country, but the fact is that the Vietnamese government has been reticent on this issue.

Therefore, the Korean government should carry out the primary investigation on its own and save the joint investigation for later.

Investigating war crime allegations against one’s own armed forces is not only reasonable, but indeed obligatory. That investigation would cover documents in the possession of the Korean and American governments and the testimony of veterans. As regards the testimony of the Vietnamese victims, investigators could avoid impinging upon Vietnam’s sovereignty by only collecting the testimony of those who volunteer to give it.

Three methods could be considered for the method of the Korean government’s separate investigation. First, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission could carry out a comprehensive ex officio investigation as the government body currently responsible for investigating past issues.

Five victims of a massacre carried out in the village of Hà My in which over 130 people were killed on Feb. 24, 1968, already asked the commission to investigate the incident in 2020, but the commission deferred the investigation indefinitely citing political liability.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission could decide to open an investigation into the Ha My massacre and then launch a comprehensive investigation into other massacres on its own prerogative.

Second could be the establishment of a commission of inquiry under the Ministry of National Defense as proposed by the Presidential Commission on Policy Planning in 2018.

This would be the same method that was used with the May 18 Democratization Movement Truth Commission, which was launched in 2017. This process would entail setting up a committee led by the private sector under the Ministry of National Defense's instructions and guarantee the committee’s period of activity for about three years.

The third method would be to establish an independent fact-finding body through legislation. To this end, a bill had been proposed in the 20th National Assembly but was eventually scrapped due to a lack of time to pass it. Democratic Party lawmaker Kang Min-jung is now preparing a similar bill in the current 21st National Assembly, but this time with many more lawmakers backing it than the previous one.

Saying Vietnam doesn’t want Korea to act is inaccurate

The main reason the South Korean government has avoided digging into the truth of these cases is allegedly because of the Vietnamese government’s own passive attitude regarding the issue. However, to rationalize inaction in this way is wrong in two respects.

First of all, the Korean government has to apologize and offer compensation to the Vietnamese victims, not the Vietnamese government. In a situation where victims went as far as filing a lawsuit against the Korean government and even winning, how long can South Korea use the excuse of the Vietnamese government’s supposed passivity to be passive itself? The victims in Vietnam want an apology and restitution.

Also important to note is that the attitude of the Vietnamese government is, in fact, also changing. For example, Vietnam’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs made various remarks last week in connection with the court ruling in Korea.

A deputy spokesperson at the ministry acknowledged on Feb. 7 that the Phong Nhị massacre was “one of many massacres committed against the Vietnamese people by foreign troops at the end of the 20th century” and that the Vietnamese government was “keeping an eye on South Korea’s ruling with great interest.” The spokesperson also emphasized how “Vietnam attaches great importance to protecting the due rights of the Vietnamese people.”

The official view of the Vietnamese government is that the massacre is a historical fact and, although the government does not step forward directly regarding the issue, it does guarantee the victims’ exercise of their rights.

The South Korean government must swiftly prepare for a first round of investigations.

Below are the words of Lê Chí Thành, a retired Vietnamese general, published in the Hankyoreh 21 magazine in December 1999.

“Gather representatives of the people, reporters, government representatives, and representatives from the Ministry of National Defense to form an investigation team. And come here and hear the stories of the locals firsthand. What the Fierce Tiger Division did to our residents along Road 19 in Bình Định Province. What kind of pain the Korean military inflicted. Please come and know the truth.”

We must finally respond to this deserving demand.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/8317138574257878.jpg) [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father![[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms? [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0423/3617138579390322.jpg) [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 2Senior doctors cut hours, prepare to resign as government refuses to scrap medical reform plan

- 3[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 4Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 5Opposition calls Yoon’s chief of staff appointment a ‘slap in the face’

- 6New AI-based translation tools make their way into everyday life in Korea

- 7Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 8[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 9Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 10Korean government’s compromise plan for medical reform swiftly rejected by doctors