hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

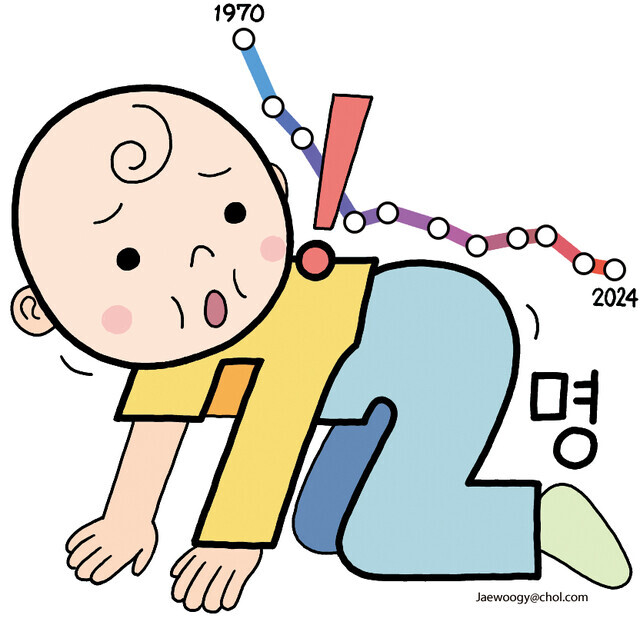

[Column] Anatomy of a falling birth rate, from 4.53 to 0.72 in Korea

Since World War II, rising populations in developing countries have been a risk factor inhibiting economic growth. In Korea’s case, the number of births began skyrocketing shortly after the Korean War. So many children were born that the years from 1955 to 1963 have become known as the “baby boom” period.

In 1970, the national statistical office began calculating a total fertility rate index, which showed how many children on average women were expected to bear during their lifetime. At the time, the rate was 4.53.

According to data from the National Archives of Korea, the total fertility rate in 1960 was 6. Even among developing countries, that was remarkably high.

Among the major contributors to lowering the birth rate at the time were family planning efforts such as the “3+3+35” campaign which called on couples to restrict their number of children to three born three years apart before turning 35.

As recently as the 1950s, the private sector was a central force in these family planning efforts, including US missionaries. A core aim was the preservation of mothers’ and children’s health and a reduction of infant deaths and deaths during childbirth.

As these efforts were undertaken in earnest as part of the five-year plan for economic development implemented in 1962, the approach shifted to government leadership. This was based on the conclusion that swift economic growth could not be achieved unless the population increase was contained. Administrative capabilities were marshaled to provide contraceptive materials and methods and educate the public.

These proved successful enough to reduce the fertility rate to fewer than 4 by the 1970s, with a level of 3.77 recorded in 1974. Still, the number of births did not fall immediately. In 1971, a total of 1,024,773 live births were recorded, a level roughly on par with the years in the early 1960s when the birth rate stood at 6.

That’s because the population of women of childbearing age (15 to 49 years) had also increased. As the baby boomers began having children of their own, the number of births remained high for a while. Also contributing here were attitudes strongly favoring the birth of sons.

Policies to curb birth rates continued with the “Have Two Children and Raise Them Well” campaign in the 1970s and the “Live Youthfully with One Child, Live Broadly in a Narrow Land” campaign in the 1980s.

In 1983, there was a “pan-national resolution to prevent population explosion” campaign, which shared the warning that “with no halt to population growth expected until the year 2050, economic and social development will end up naturally delayed unless the population increase can be inhabited ahead of time.”

The government’s family planning efforts did not end until 1996, by which time the total fertility rate had fallen to 1.57. The tide had begun shifting in 1983, when the rate reached 2.06 — below the 2.1 replacement level for the current population. In 1984, it stood at 1.74, remaining at roughly the same low level for the next decade.

Now people were presenting the reverse argument: that excessively restricting population growth would be harmful to the economy. It was a turning point for birth control policies that had continued for nearly half a century.

Since 2005, the government has been battling mightily against the decline in the fertility rate, presenting various measures to address the low childbirth numbers.

Demographic experts view the year 2015 as another inflection point for population indicators. As recently as that year, the fertility rate was still showing slight ebbs and flows. In 2016, it began nosediving.

In 2018, the rate stood at 0.98. It has not climbed above 1 since then.

The decline in actual births also became more pronounced around the same time, remaining below the 400,000 line since 2017. Analysts have suggested that this is due to the combined influences of a drop in marriages since the 1960s and a sharp decline in the fertility rate for married women since 2012.

Last year, the total fertility rate hit a new all-time low of 0.72. At this point, it had become the subject of global attention, with the foreign press devoting major coverage whenever new indicators were announced.

A total fertility rate below 1 is seen as something only possible in a situation like a war or regime collapse. Among members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the average rate stood at 1.58 as of 2021; Korea is the only member with a level under 1.

In 2023, the average age of Koreans having their first child was 33.0 years — significantly higher than the OECD average of 29.7 years in 2021.

Comparing the low birth rate phenomena in Korea and Japan, Nikkei senior staff writer Hiroshi Minegishi concluded, “Whereas many members of Japan’s younger generation say that they want children but cannot have them, there are a growing number of Koreans — women in particular — who say they don’t want to marry or have children.”

Indeed, there seems to be a strong sense among women in Korea that with its worsening competition and economic inequality and its lack of gender equality, Korea is not a society to raise a child in. This explains why measures to provide support for the child-raising environment are unlikely to yield results.

By Hwang Bo-yon, editorial writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing? [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0705/2917201664129137.jpg) [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?

[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?![[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0703/8717199957128458.jpg) [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor

[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor- [Column] How opposing war became a far-right policy

- [Editorial] Korea needs to adjust diplomatic course in preparation for a Trump comeback

- [Editorial] Silence won’t save Yoon

- [Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated

- [Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war

- [Correspondent’s column] Who really created the new ‘axis of evil’?

- [Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

Most viewed articles

- 110 days of torture: Korean mental patient’s restraints only removed after death

- 2What will a super-weak yen mean for the Korean economy?

- 3Real-life heroes of “A Taxi Driver” pass away without having reunited

- 4Koreans are getting taller, but half of Korean men are now considered obese

- 5End of an era? Fans wait to see what Billboard rule changes will do to BTS rankings

- 6Ahead of 2018 Olympics, hanok village opens in Gangneung

- 7Members of North Korea’s cheerleading squad reflect on their Olympic experience

- 8Former bodyguard’s dark tale of marriage to Samsung royalty

- 9Beleaguered economy could stymie Japan’s efforts to buoy the yen

- 10[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?