hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Why Korea’s hard right is fated to lose

By Pak Noja (Vladimir Tikhonov), professor of Korean Studies at the University of Oslo

Recent polls about support for political parties in Germany and France are sure to be horrifying for any student of history.

Germany’s Social Democratic Party (SPD) has a storied history dating back to its establishment in 1863. It’s the same party that played such a big role in ending the Cold War with Ostpolitik (Eastern Policy), which it adopted after coming to power in 1969. But despite its decorated history, the SPD is currently polling around 15%–16%, behind the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), which is at 19%–20%.

In France, the far-right National Rally is currently seeing support of 29% or so, more than doubling the combined support for the equally historic Socialist Party (10%) and Communist Party (3%). This is the first time in postwar history that the far right has dominated the left to such an extent in these two countries.

The years since the global financial crisis of 2008 have witnessed the resurgence of so many far-right parties, movements and organizations that it could easily be called a hard-line conservative era.

That’s also true in the world’s emerging economies. Modi in India, Putin in Russia and Erdoğan in Türkiye are all figures from the hard right who have erected systems to keep them in power.

Even in the center of the global order, the growing strength of the hard right is hardly an exception. While the Trump phenomenon in the US is the most infamous case, the far right enjoys burgeoning popularity in several European countries.

While the “Swedish model” tends to signify social democracy and the welfare state, Sweden today is actually ruled by a conservative coalition government, while the Sweden Democrats, the country’s most radical far-right party with neo-Nazi links, is supported by around 20%–21% of the electorate.

In Austria, one of just a handful of European countries to maintain neutrality, around 28–30% of voters currently favor the Freedom Party of Austria, which was established by members of the Nazi Schutzstaffel (SS).

Just as in the US, figures who resemble Trump to varying degrees periodically take the stage in various countries across Europe.

However, the dilemma for parties of the left in North America and Europe is not merely the rise of far-right parties. The even bigger problem is that those far-right parties are gradually winning the support of the very workers who were the left’s traditional support base.

France’s National Rally is the choice of so many workers that it’s the “new labor party.” And in the German state of Brandenburg, 44% of working-class voters cast their ballots for AfD in the parliamentary election four years ago.

High-skilled workers at big companies, high-income earners and permanent employees continue to vote for traditional center-left parties. But workers at small companies with lower wages and less employment stability are leaning more toward far-right parties.

The tragic and troubling tendency for far-right parties to assume the role of the “new labor party” is rooted in the recent history of the world order. In the wave of neoliberal globalization that lasted through 2008, center-left parties generally either supported or failed to actively resist a series of neoliberal policies that created large numbers of precarious workers and allowed factories to be offshored, hollowing out the industrial heartland.

Neoliberal globalization may have brought certain benefits, such as cheap imported goods, for regular workers at large corporations and in the public sector who had stable jobs and owned homes, but for more vulnerable members of the working class, it meant growing instability, rising rents and belt-tightening.

When the restoration of national sovereignty became the word of the hour following the collapse of globalization in 2008, many victims of globalization in the working class were tempted to migrate toward far-right parties that emphasized sovereignty, the national economy and the national community, along with restrictions on immigration. Another reason these far-right parties were able to absorb vulnerable members of the working class is that (at least in Europe) those parties no longer call for cutting welfare, but instead advocate “an appropriate level of welfare for the national community.”

In the end, a substantial number of the center-left parties that entrusted their fate to the wave of neoliberal globalization are undergoing a potentially fatal crisis along with globalization itself.

But one curious fact is the very tangible difference between the hard right in North America and Europe and the hard right in South Korea.

In North America and Europe, emphasis on “sovereignty” plays a major role along with the appeal of anti-immigrant sentiment. For instance, AfD enthusiastically welcomed Trump’s decision four years ago to pull out some of the US troops stationed in Germany. The party’s argument was that a Germany with no US military bases is a sovereign Germany.

In France, the National Rally claims to want to extricate France from NATO’s integrated command, though it’s unclear if this is a realistic campaign pledge.

While we should avoid simplistic comparisons of Europe and Korea, given the fundamental differences in their respective circumstances, the tendencies that are evident on the European hard right are nowhere to be seen in the Korean hard right, which is currently in power. In fact, Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol is reducing the scope of Korean sovereignty.

The same is true on a socio-economic level. The far-right populists of Europe speak of a “national community” from which immigrants are excluded but readily acknowledge that redistribution and the public sector are required to keep that community knitted together. Perhaps the best-known example of that is the National Rally, now the most popular party in France, which calls for increasing welfare spending.

In the case of Norway, welfare spending as a share of GDP actually jumped from 23% to 30% in 2013–2021, when the country was governed by a conservative coalition that included the far-right Progress Party.

But in contrast with these European examples, Yoon began his presidency by slashing the budget for such welfare programs as expanding nursing homes, building a children’s rehabilitation hospital, expanding daycare programs and preventing school violence. In short, Yoon is moving in a completely different direction from the successful hard-line conservatives of Europe.

The European fervor for the hard right and its drive for a “national community” and “the restoration of sovereignty” is unlikely to die down anytime soon. But it’s doubtful whether voters will warm to Yoon’s fondness for cutting taxes on the wealthy, given his apathy for national sovereignty or community.

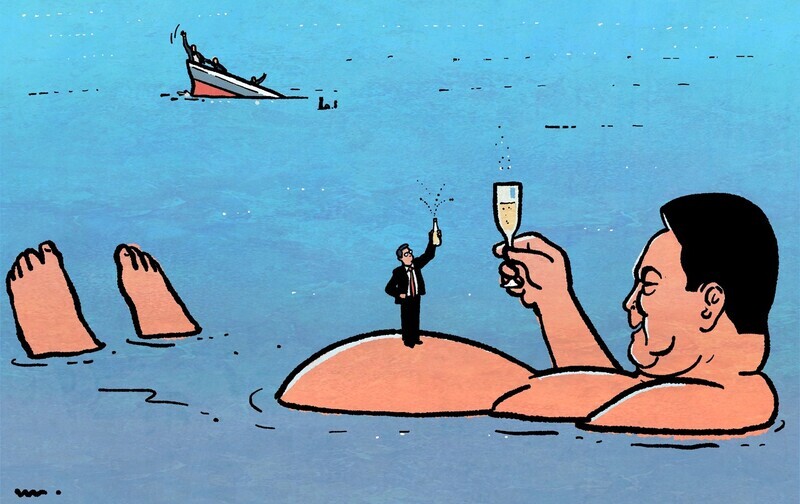

I can’t see a very bright political future for Korea’s distinctive “elite hard right,” which only cares about the upper and middle classes. History teaches us that political parties that only serve the interests of a tiny minority will eventually, but inevitably, go bust.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing? [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0705/2917201664129137.jpg) [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?

[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?![[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0703/8717199957128458.jpg) [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor

[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor- [Column] How opposing war became a far-right policy

- [Editorial] Korea needs to adjust diplomatic course in preparation for a Trump comeback

- [Editorial] Silence won’t save Yoon

- [Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated

- [Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war

- [Correspondent’s column] Who really created the new ‘axis of evil’?

- [Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

Most viewed articles

- 110 days of torture: Korean mental patient’s restraints only removed after death

- 2What will a super-weak yen mean for the Korean economy?

- 3Real-life heroes of “A Taxi Driver” pass away without having reunited

- 4Koreans are getting taller, but half of Korean men are now considered obese

- 5End of an era? Fans wait to see what Billboard rule changes will do to BTS rankings

- 6Former bodyguard’s dark tale of marriage to Samsung royalty

- 7[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?

- 8Can the IPEF deliver the US dream of an Asian economy without China?

- 9Japan’s lack of transparency on Fukushima water is sparking fear in neighbors, says Japanese expert

- 10Beleaguered economy could stymie Japan’s efforts to buoy the yen