hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Behind factional animus of Korean politics, victim mentality festers

Political polarization, which highlights the differences between parties, isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Even if the status of the “ruling” party changes every other election, the public would have no reason to care about participating in politics if policies don’t change and their lives go unchanged.

As such, a democracy can only flourish when competing parties offer their own solutions to major troubles and issues in society so as to drive voters to polling stations.

However, emotional polarization between political parties, which can be demonstrated in the “in-party favoritism, out-party animus” mindset among political elites and activists, and their supporters, can be exceedingly harmful.

The most concerning issue is how such stances render elections useless. When people base their votes on “sides” rather than sitting down to think about whether they like or dislike certain policies offered by parties or assessing whether those in authority or parties are doing a good job, voting becomes a mere issue of winning or losing.

Emotional polarization is activated by affect, triggers that can wound one’s pride or prompt disgust at one’s opponent. If an emotional narrative based on the ways people talk about politics — “Why are they going so far?” or “Are they trying to end us once and for all?” — emerges, clashes between differing political parties are bound to turn more rough-and-tumble.

If we look back closely at Korea’s political history, there we’ll see two major such triggers. The investigation of former President Roh Moo-hyun and his death in 2009, and the impeachment of former President Park Geun-hye and the purges of deep-rooted vices and corruption in 2017.

The Hannara Party — a forerunner of the current PPP — won a landslide victory in the 2007 presidential election, beating the opposition by 22.5 percentage points. The party then took 153 seats in the National Assembly in the general election in the following year — making the Democratic Party’s 81 seats look measly.

With such a massive lead, there was no need to drag a former president into political warfare. So why did they?

The drama of their demise began in May of that year, right after the general election, when people began protesting controversial beef imports from the US. People held massive rallies in Gwanghwamun Square, decrying the South Korean government’s kowtowing acceptance of US beef that had potentially been infected with mad cow disease. Eventually, President Lee Myung-bak had to issue a public apology. His administration was in a bind. Public approval ratings for Lee fell to 21.2% (Gallup Korea, May 2007), and then to 17.2% (Media Research, June). The bind turned into a crisis.

“The Lee Myung-bak administration tried to exploit the investigation of former President Roh Moo-hyun to create a political distraction.” These are the words of Lee In-kyu, the leader of the investigation into Roh.

“Just six months into his presidency, Lee was already seeing calls for his resignation. He had to issue a public apology. At that time, however, former President Roh was becoming increasingly outspoken about the state of Korean politics. More and more people began visiting [Roh’s hometown of] Bongha Village, and the ruling party was feeling the pressure,” wrote Lee Sun-hyuk in “The Internal Struggles of Prosecutors.”

In short, Lee turned the prosecutors against Roh to get himself out of a jam.

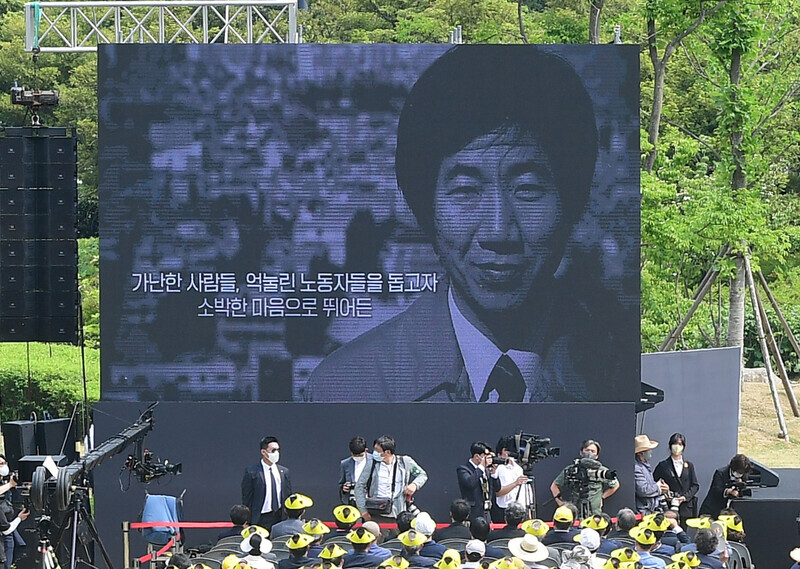

When the National Tax Service began investigating Taekwang Group Chairman Park Yeon-cha on tax evasion charges in 2008, the investigation led to the arrest of Roh’s brother in December of that year. Lee In-kyu, the prosecutor leading the investigation, and his underling Woo Byung-woo suddenly expanded the scope of the probe to include Roh. Prosecutors publicly issued a subpoena for Roh on April 30, making it a point to humiliate him. Less than a month later, Roh took his own life.

Roh had become an icon of a movement that sought to do away with the dirtiness of conventional politics. Roh was so popular he even inspired a fan club called Rosamo, a Korean acronym for “gathering of people who love Roh Moo-hyun.” His seemingly naive and down-to-earth demeanor earned him the affectionate label “fool.” Upon hearing the news of his death, Roh’s support base was devastated. Enraged.

The Hannara Party was particularly hellbent on vilifying Roh. This was different from when the party lost power due to events like the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the political alliance between Kim Dae-jung and Kim Jong-pil, and the rise of third-party candidate Lee In-jae. Some party members publicly declared that they did not acknowledge Roh as their president. They were largely responsible for the 1997 financial crisis. Moreover, the opposition formed a political alliance while their camp was divided. Obviously, they were forced to accept their defeat in the face of the Kim Dae-jung administration.

Yet they were self-assured that five years later, they would be back in power — and for good reason. At the end of his term, Kim Dae-jung’s approval ratings plummeted to 24%-26%. The situation was ripe for flipping the Blue House. Kim Dae-jung’s son had been arrested, and the ruling party was divided. Yet still, Hannara lost the 2002 presidential election to Roh by a margin of 2.3 percentage points. Despite the division between Roh and Chung Mong-joon, who had agreed to form a unified candidacy, the ruling party still won. Hannara simply was not prepared for the loss, and therefore could not accept it.

There were also concerns about the changing political landscape. Kim Dae-jung was from the Honam region made up of Korea’s southwest, a traditional progressive support base, while Roh was from Yeongnam in the southeast, which houses the traditional conservative bases of Busan and South Gyeongsang Province. The continued popularity of Roh threatened to alter this foundational support base for the Hannara faction. If that happened, they would have a massive hole in their political strategy.

After the presidential election, there was a series of investigations into illicit campaign funds. The political atmosphere was grim. Although these investigations hurt the Roh administration as well, the Hannara Party also took a beating. It was revealed that the party had been accepting illicit campaign funds in the form of truckloads of cash. The party earned the nickname “the cash truck party,” and several big-name members ended up convicted.

Lee In-kyu commented that “the illegal campaign fund investigations hurt the Hannara Party much more than they hurt President Roh,” in his book “I Was an ROK Prosecutor.” This sense of defeat drove the Hannara Party to extend an olive branch to the Millennium Democratic Party.

The Democratic Party had been suffering from internal division. When approval ratings plummeted, some party insiders called for the replacement of Roh as a presidential candidate. After the election, pro-Roh lawmakers split to form their own Uri Party. Tensions were high. The Millennium Democratic Party and the Hannara Party formed an unholy alliance and voted to impeach Roh in the National Assembly.

In the 2004 general election, there was public backlash against Roh’s impeachment. The Uri Party rode the wave of this backlash to attain a majority in the National Assembly. It was the first time that a liberal party had won a majority. Naturally, the conservatives were stupefied.

In 2012, however, the Saenuri Party defied expectations by winning in both the presidential election and the general election. The Park Geun-hye administration’s dismal handling of the Sewol tragedy, however, led to the party’s defeat in the 2016 general election. Having lost their legislative shield, Park’s twisted ties with Choi Soon-sil came to light, and Park was removed from office.

Under the Moon Jae-in administration that followed, prosecutors launched an investigative overhaul that ended with former Presidents Park Geun-hye and Lee Myung-bak and high-level government officials behind bars. The conservative party was nearly leveled.

As the well-regarded sociologist Kim Chan-ho has pointed out, socially constructed emotions rule our behavior and thoughts. Although the conservatives were humiliated in defeat, it didn’t take long before a reactionary faction rose to oppose the liberals, feeding the conditions for further political polarization.

Roh’s death and Park’s impeachment created a sense of martyrdom on both sides of the political aisle. Both sides felt wronged, plagued with a sense of guilt that they had failed to support their leaders. In both political camps, this victim mentality led to greater internal unity partnered with more extreme hatred of the opposition.

In such an environment, party members had almost no choice but to overtly declare their loyalty and band together in hatred against the opposition. A common enemy combined with a sense of victimhood results in intense unity. From 2003 to 2013, Hull City had the worst record of any club within the Premier League, yet the fans were never more united, their sense of camaraderie never stronger. The two main political parties in South Korea no longer viewed each other as opponents, but as enemies. We are the victims, and they are the perpetrators. Hatred for the other side, not sympathy or loyalty to the party, formed the crux of each party.

It’s true that impeachments — although authorized by the Constitution — have contributed to this political polarization. However, the victim mentality within each camp is at the core of the need to paint the opposition as “the enemy,” which is fomented by investigative witch hunts that are seen as nothing more than political revenge.

Whether it’s the conservatives’ witch hunt campaign against Roh or the political purges of the Moon administration, neither side can escape the criticism that their investigations were based more on revenge and political strategy rather than a sense of justice. Whether such investigations result from active planning or passive negligence, the other side views them as political retribution, and will inevitably develop an eye-for-an-eye instinct. Political and cultural polarization is the result of people internalizing this “victim-revenge” narrative.

So let’s ask the question: Is this political and cultural polarization solely the fault of the political elites? What are we to make of the increasingly diminishing disparity in public support for the conservative camp and their liberal opposition?

By Rhee Cheol-hee, former lawmaker and former senior secretary for political affairs under President Moon Jae-in

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 3[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 7[Special report- Part III] Curses, verbal abuse, and impossible quotas

- 8Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 9S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 10The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan