hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Life in front of a nuclear reactor

I’m a 73-year-old woman living about 1.2km from the Wolsong nuclear power plant. The street where I live is just 300m from the restricted area around the reactor, where ordinary people aren’t allowed to live or even enter. I can see the nuclear reactor from in front of my house.

I moved here in August 1986. My husband and I economized in our food and clothing during his 13 years at the office and then bought a little farm with the money we’d saved. Back then, the Wolsong nuclear plant was connected to Ulsan by about 30km of unpaved roads. On the day we moved here — bringing along our three children and carrying our luggage in a three-wheeler — my youngest child was barely 6 years old and I was 39.

Life on the farm was rich, though it didn’t make us wealthy. We were surrounded by the glory of nature, a beauty that changes with the seasons. All three of our children went to university and got married. I didn’t ask for much; I was happy just to look forward to taking care of my grandchildren on the farm, just as I’d raised my children there, and feeding them homegrown food.

Along the way, the number of nuclear reactors in front of our house increased one by one. Back when I moved here, there was only a single reactor (Wolsong-1), and the residents didn’t even know what a reactor was. We just figured it was a factory that made electricity. Each time a new reactor was built, Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power (KHNP) talked about how the plant was good for the local community and would help the local economy.

Locals believed the KHNP when it said the nuclear reactors were a good thing, safe and affordable. We thought of the KHNP as the agency in charge of the complex technology of a nuclear plant, as being like the government. Back then, we didn’t think the government, or the KHNP, would try to deceive us. Even when farmland and houses were appropriated to build more reactors, leaving us with less land to farm on, and even when there were six reactors clustered together, we didn’t want to complain about the government’s business.

But there were a number of incidents that aggravated residents’ distrust in the nuclear reactors. First we learned that the reactors were being supplied with knock-off parts, and then we found out that a bundle of spent fuel rods had fallen down while nuclear fuel rods were being replaced at Wolsong-1, causing a radiation leak — an accident that was kept secret for five years. The residents were anxious about how much radiation had leaked in that accident. But the KHNP told us the leak was minimal and that we had nothing to worry about. Once again, the residents assumed the KHNP was lying.

In 2012, I was diagnosed with thyroid cancer and received an operation a year later. The weird thing was that I had no family history of cancer. I was told that radiation was a major cause of thyroid cancer. I also learned that nuclear reactors are always releasing radiation, even when there isn’t an accident.

Given the large number of thyroid cancers among my neighbors, we enlisted the help of experts in 2015 and decided to get tested for internal exposure to tritium, an isotype of hydrogen. Forty of the residents, including children as young as five years old and elderly people as old as 80, submitted urine samples for testing. My husband and I were among those tested, along with my daughters, sons-in-law, and grandchildren.

While we were waiting for the testing results, I couldn’t shake my anxiety. Surely we’d be fine, I thought — we just had to be! The two months I waited felt like 20 years. When I finally got the test results, my mind went blank. All 40 of the residents tested had suffered internal tritium exposure. The shock was unbearable, but the greatest shock of all was that my four-year-old grandson had radiation in his little body.

(The Korea Federation for Environmental Movements said at the time that “international studies have found that long-term exposure to tritium carries the risk of causing leukemia or cancer and that young children are especially sensitive.” Tritium reportedly doesn’t show up in tests done on the general public.)

KHNP refuses to take responsibilityAnd so we informed the KHNP about the test results. We explained that we couldn’t live there any longer and asked to be relocated. But the KHNP responded by saying that it had no means of relocating us.

I was tested again for internal tritium exposure in January 2020, after Wolsong-1 was shut down, and the radiation level was lower than when the reactor had been in operation. That’s why I think Wolsong-1 should stay shuttered.

Nowadays, some people seem to be pushing for the reactors’ reactivation. That’s a ridiculous idea. Keeping the reactor shuttered means that less spent nuclear fuel is produced. Who’s going to take responsibility for the nuclear waste that has to be managed for 100,000 years? Before we start talking about how to store the high-level radioactive waste, we need to close not only Wolsong-1 but also Wolsong-2, -3, and -4, reactors that release more radiation and produce more spent nuclear fuel than any others in the country.

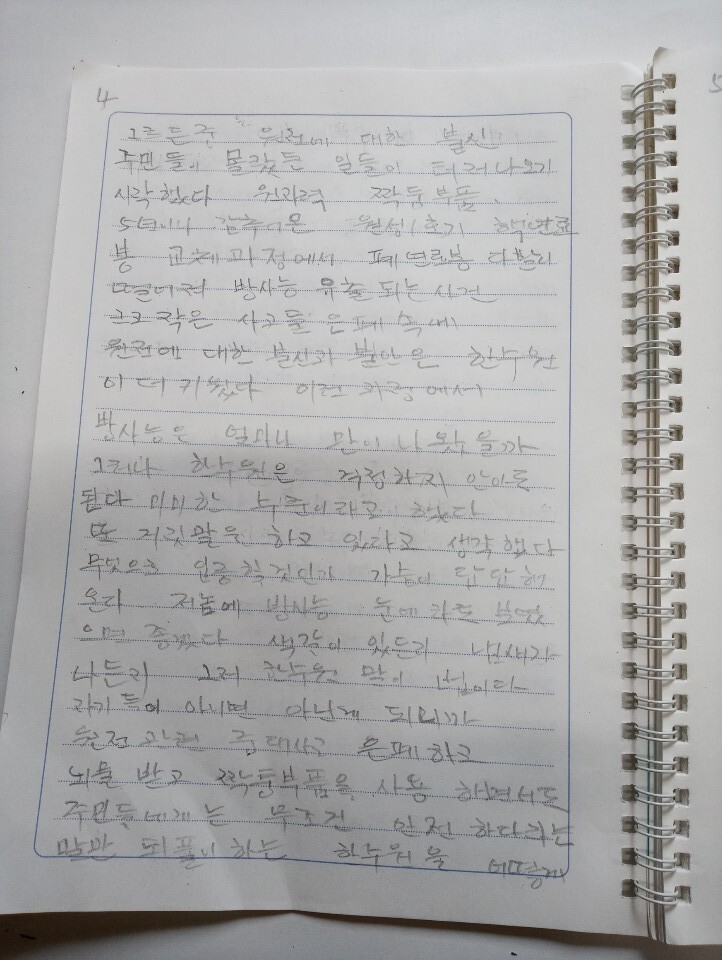

Editor’s note: This essay is based on a diary entry that Hwang Bun-hui sent Kim Yeong-hui, head of Sunflower, a Korean group of lawyers who oppose nuclear power. The entry has been condensed and updated with technical terms, but otherwise it is faithful to the original.

Hwang Bun-hui, a resident near the Wolsong nuclear power plant

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 3Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 4AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 5[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 6Noting shared ‘values,’ Korea hints at passport-free travel with Japan

- 7Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 8Gangnam murderer says he killed “because women have always ignored me”

- 9South Korea officially an aged society just 17 years after becoming aging society

- 10The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan