hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

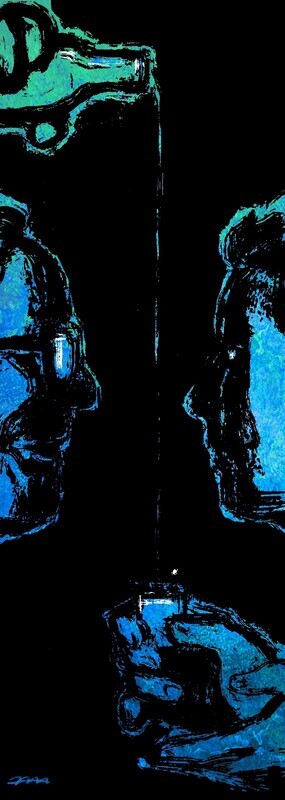

[Column] “Hoesik” as ritual of hierarchical obedience

There are a lot of differences between South Korean and Norwegian universities, but one of the most noticeable is how the neighborhoods near them look. For the most part, South Korean university campuses are surrounded by nightlife. You see a number of restaurants where students can eat and coffee houses where they can study, but you also see quite a few pubs and karaoke rooms.

Northern European universities definitely have places on campus where faculty and students can eat at a discount, but while you might see a few coffee houses outside of them, you won't find the kind of nightlife districts that South Korea has.

It isn't just universities. The sort of nightlife areas often seen at the bases of Seoul's forests of office buildings is nowhere to be found in downtown Oslo, where the company headquarters and government buildings are located. There are obviously nightlife spots in the city, but they aren't very close to the office workers' places of employment. That's because there is no need for them to visit nightlife spots as an extension of their "work."

Norway is by no means a non-drinking country. At 7.7 liters, the average Norwegian's yearly alcohol consumption is a lot less than the 12.3 liters consumed by the average South Korean adult. But despite efforts over the last century to set high alcohol prices by establishing a state monopoly on alcohol sales, they haven't succeeded in eliminating the country's drinking culture.

But the very notion of creating a connection between workplaces and drinking parties — known in Korean as "hoesik" — is untenable in a society characterized by a balance between capital and labor.

What is a "workplace"? It is merely somewhere for workers to sell their labor and collect wages in return. Beyond their eight hours of work on weekdays, the employee selling their working hours owes nothing to their employer.

We don't require the owner of a supermarket to drink with their customers. Similarly, it is legally indefensible for the people selling working hours to be dragged off and ordered to drink by their workplace managers.

In a normal society, it would be grounds for a lawsuit for a manager to even contact an employee outside of working hours for work-related purposes. What about South Korea?

The year before last, the employment matching platform SaraminHR surveyed 456 workers about handling work-related duties via mobile messaging services. The results showed 68.2% of respondents reporting that they had received work requests via messaging services outside of their working hours. This is an excellent illustration of just how far South Korea's labor-management practices are from "normal."

In addition to work-related requests outside of working hours, effectively forcing workers to attend drinking parties is another example of a human rights violation that many South Korean workplace managers still mistakenly view as "normal."

To be sure, the pressure to attend hoesik has eased significantly as sensitivity to human rights issues has developed. In the late 1990s, when I experienced the "workplace culture" in South Korea, it was common to find companies and universities where avoiding a hoesik was treated as a bigger "sin" than missing work.

To overtly refuse to attend required more courage than taking part in a demonstration that was being put down by heavily armed riot police. Simply dodging it would be seen as tantamount to defying the manager's authority.

How are things today? Last year, the job portal site JobKorea conducted a survey in which 659 workers were asked about hoesik. Forty-five percent said they were "free to choose" whether to attend, while no fewer than 41% said they "worried how it would look" if they didn't. Another 13% of respondents (multiple responses were allowed) said attendance was "mandatory."

So while things are improving, a majority of South Korean workers are still forced to take part in group "nightlife activities." It's another part of the landscape of what people have referred to as "Hell Joseon" or "Hell Korea."

Even with the COVID-19 emergency prompting authorities to plead with people not to hold gatherings, no fewer than 22% of respondents said that hoesik were "still happening." The hoesik is seen less as a simple occasion for eating, drinking and singing together – and more as an essential "ritual" for companies that amount to quasi-kingdoms.

By its nature, a ritual is a highly symbolic procedure that reaffirms and cements social relationships. But what sort of relationships does the hoesik ritual actually reaffirm?

When asked about the significance of hoesik, workplace managers might stress the "cultivation of a sense of unity and solidarity." But if we look at and take part in the typical hoesik through an anthropologist's eyes, we swiftly see that the main thing being reinforced there is hierarchy.

Hoesik attendance carries a strong sense of compliance with a superior's "invisible" orders. And while the hoesik practice of subordinates pouring drinks for their boss does seem to have markedly declined, it only takes a moment's observation to see who the superior is and who the inferiors are.

The bosses overseeing these (unofficial) events hear their subordinates' complaints, listen to their requests and make them all sorts of promises — in exchange for an implicit demand of continued obedience. (Of course, a survey of such subordinates four years ago by the online research firm Macromill Embrain found that just 19% of bosses actually honored those hoesik promises.)

The typical hoesik scene is one where the employees are doing their utmost to conceal their reluctance while the boss strains to feign warmth.

In addition, we often see examples of illegal actions in the "flush of alcohol," including harassment, abusive language and even violence. It's a hellish experience for subordinates and a potentially expensive one for bosses. So why on earth do they continue to practice this ritual?

It seems to have something to do with a strategy by South Korean companies to claim profits. South Korea touts itself as having become an "advanced country," but its labor productivity is still a mere 45% of, say, Norway's.

To maximize profits, companies offset their relatively low efficiency by forcing employees to work extremely long hours. Even when the government imposes a 52-hour maximum per week, that "cap" exists only on paper, especially at manufacturing and construction workplaces. Surveys of the members of various labor unions show that actual working hours remain around 60 per week.

To treat workers as machines that can be used at one's convenience requires first rendering any distinction between working hours and personal time impossible by "colonizing" their time at home in the evenings and weekends with work-related requests via KakaoTalk. At the same time, many workplaces also mandate the hoesik as a ritual of hierarchical obedience, where the boss plays the part of the "kindly patriarch."

It becomes far easier to force people to work illegally long hours when you have the sort of patriarchal "family-like" environment that the hoesik helps to foster.

A good country for workers is one where they can put in their eight hours of work, and then forget all about their workplace on evenings, weekends and holidays. Getting South Korea to that level will require stiffer punishments for forced hoesik, along with efforts to quickly promote the view that a good company is one that doesn't do hoesik.

By Pak Noja (Vladimir Tikhonov), professor of Korean studies at the University of Oslo

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 2Up-and-coming Indonesian group StarBe spills what it learned during K-pop training in Seoul

- 3‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 4[News analysis] Using lure of fame, K-entertainment agency bigwigs sexually prey on young trainees

- 5[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 6Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 9Report reveals toxic pollution at numerous USFK bases

- 10[Editorial] Statue should not be central concern of comfort women issue