hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Korea never got its revolution of ’68

By Pak Noja (Vladimir Tikhonov), professor of Korean Studies at the University of Oslo

Last year, I spent a few months at a Korean university. It was my first extended stay in Korea in some time, and I won’t forget the pleasure of looking up and reading precious sources in Korean libraries that aren’t to be found at any library in Europe.

But I also came to feel a keen and fundamental difference between the mood at that Korean university and the mood I’d grown accustomed to at the University of Oslo.

When it comes to differences, one tangible one is the state-of-the-art appearance of new buildings at Korean universities, especially in comparison to any European university.

But the biggest contrast of all has nothing to do with the outward appearance. Rather, it’s the difference between how human relationships are built and how power relationships operate.

A recurring thought I have is that the janitorial staff are the biggest heroes of the university. In our present era, when education can be carried out in various ways online, universities can get along just fine when numerous instructors go on leave or take trips for months at a time.

But if the university bathrooms went without cleaning for a single day, the stench and inconvenience would make it hard for research or teaching to get done.

Therefore, I’ve always taken for granted the habitual greeting that students, teachers, and administrators at the University of Oslo extend to custodians they encounter in the hallways.

For people in their middle years, who are starting to suffer from bad backs and other chronic conditions, janitorial work is much more taxing than writing or teaching. That’s something I’ve experienced firsthand, since I’m in charge of cleaning at home.

On top of that, teachers and administrators at the University of Oslo tend to regard the custodial staff as “colleagues,” since they’re all members of the same labor union.

At Korean universities, however, I’ve never seen a professor extend a greeting to a janitor first. It’s hard to even imagine professors and janitors belonging to the same union.

Professors themselves are divided into separate unions, depending on whether they’re regular or irregular workers, and the two unions hardly ever cooperate in their campaigns.

As an inveterate coffee drinker, I consider the coffee sold at Korean universities as being superior to what’s available at the University of Oslo. That’s true of the flavor, but also of the wonderful prices — not even half of that in Oslo.

At the Oslo cafeteria, people generally only buy coffee for themselves. But at Korean university cafeterias, every day I could see younger people (typically women) loading a big takeout container with several cups of coffee and napkins and then heading off somewhere.

When asked, they’d often say they were taking the coffee to a “professor” or their “seonbae,” meaning fellow students with seniority in their program.

To be sure, some of those coffee deliveries may have been pure acts of kindness. But I get the strong impression that such behavior isn’t always voluntary, especially given recent allegations that the newly appointed education minister exploited her authority while serving as a university professor.

In my mind’s eye, I can still clearly see those young women trudging toward the distant research wing with that big takeout container in their hands. I wonder if they were TAs, in charge of aiding professors’ work.

If I were to list each difference I sensed between the two schools, I’d probably end up with quite the tome.

Many Korean professors would probably find it odd if they saw Oslo’s student representatives making a face-to-face request for professors to improve their pedagogy during a faculty meeting after receiving student evaluations about professors’ lectures. But that’s just standard procedure in Oslo.

There are definite differences not only in meetings’ agendas and formats, but also in participants’ outfits. The formal attire and neckties that are still common sights at Korean universities are hardly ever seen in Norwegian universities, aside from on very special occasions.

But rather than rattling off differences one after another, I suppose it would be more helpful to think about what the root cause of such deviations might be.

There has never been, nor could there have been, a modern society that was nonauthoritarian from the outset. In the Norway of the 1950s, when social-democratic reforms were underway, there was a huge distance between professors (who were high-income public servants) and their students on the one hand and universities’ facility staff on the other.

The biggest factor that helped level the top-down relationships found not only in academe but in Norwegian society as a whole was the anti-authoritarian revolution of 1968. That was the point after which formal wear and neckties disappeared from view and student representatives were allowed to participate in university administration.

To be sure, the authoritarian culture that had calcified over centuries didn’t collapse all at once. Casual abuse of power — such as sending junior associates on coffee runs — continued in everyday life in Norway and several other countries in Northern Europe until the 1970s and 1980s, when members of the generation that had personally experienced and directly or indirectly participated in the 1968 revolution put down roots in academe and other areas of society.

The 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s were a much more revolutionary time in Korea than in Europe. Unlike the mostly bloodless revolution in Europe in 1968, democracy activists in Korea were often aware that they might be tortured or even killed.

But at the same time, their revolution had different aims. While there were many radicals in Korea’s democracy movement, the movement’s common and overarching goal was a political transformation — that is, bringing down the dictator. A reform-oriented civilian government represented the victory desired by most members of the movement, and authoritarianism throughout society was treated as a secondary problem.

In that context, democracy activists of the past were completely capable of standing against progress on social issues. That was evident when Lee Chul, who had once been sentenced to death during the democratization movement, fired female train attendants working irregular positions during his tenure as president of the Korea Railroad Corporation, or KORAIL, from 2005 to 2008.

But the leaders of Europe’s 1968 revolution were generally not interested in taking power and sought to make authoritarian power structures more horizontal while democratizing society as a whole in a way that went beyond political change.

While they never managed to achieve their ultimate goal of building an eco-friendly and pacifistic democratic society, their assault on authoritarianism and their extension of human rights have changed Norwegian society and societies across Europe for good.

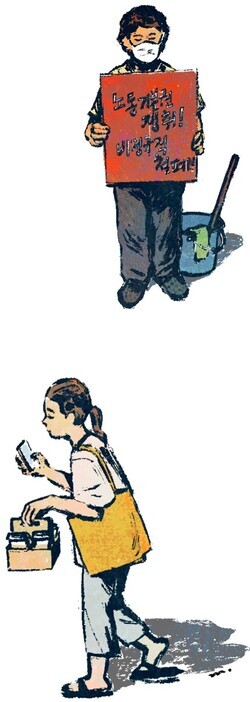

Today, Korea is an extremely atomized society that has lost the cohesion needed to pursue social revolution. Nevertheless, the genuinely progressive forces in society, including labor activists among irregular workers, continue their struggle against the abuse of power under extremely difficult circumstances. Even if we can’t join their struggle, sending them our support and encouragement is the first step toward building a better society.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’ [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/5217153290112576.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’![[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/7717153284590168.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change- [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

- 2[Book review] Who said Asians can’t make some good trouble?

- 3Korea poised to overtake Taiwan as world’s No. 2 chip producer by 2032

- 4Yoon rejects calls for special counsel probes into Marine’s death, first lady in long-awaited presse

- 5Korea likely to shave off 1 trillion won from Indonesia’s KF-21 contribution price tag

- 6[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

- 7[Photo] ‘End the genocide in Gaza’: Students in Korea join global anti-war protest wave

- 8S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 9How many more children like Hind Rajab must die by Israel’s hand?

- 10Yoon voices ‘trust’ in Japanese counterpart, says alliance with US won’t change