hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] Standing in the face of catastrophe

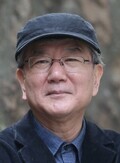

By Hong Se-hwa, director of Jean Valjean Bank and Simple Free People

On the afternoon of Sept. 24, around 35,000 people gathered in the Sungryemun, City Hall, and Gwanghwamun areas of central Seoul to march for climate justice.

“We can’t live with climate disaster!” they shouted. “Put people ahead of profits!”

Whether it was a good omen or a mirage, a rainbow cloud hung in the sky over the marchers for some time.

“Rich countries commit the crime; poor ones suffer the punishment.” This was the title of an article in a special issue of the Hankyoreh 21, which reported on the situation in Pakistan.

“In the climate crisis-vulnerable nation of Pakistan, which was responsible for 0.4% of greenhouse gas emissions, a third of the country was left underwater as a monsoon dumped record levels of rain on it,” the article said. The inundated area was larger than the United Kingdom, which had once been the country’s colonial ruler.

The article also stated that 1,559 people had died in the flooding, including 551 children. “6.4 million people were displaced by the flooding, among them 3.4 million children,” it said. “The 33 million people affected by flood damages amounted to one out of every seven in the population.” These numbers — poor people in a poor country — left no room for narratives.

The Kyunghyang Shinmun newspaper quoted information shared by the international relief organization Oxfam, which said that the highest-ranked 10% of the world’s population in terms of income were responsible for over half of greenhouse gas emissions between 1990 and 2015, while the bottom-ranked 50% accounted for just 7%.

There’s a historical background to this absurd state of affairs. Nearly all the high-income countries were colonizers, while most of the low-income countries were colonies.

The pain and suffering caused by slave labor and colonization did not die with their ancestors. Plundering of resources and monoculture farming by colonial overlords left the descendants without an economic foundation to develop through their own capabilities.

This wasn’t all. The borders arbitrarily drawn by the colonial rulers, along with neo-colonial policies that took advantage of local rulers, left ordinary people faced with constant civil war and tyranny.

Even those who succeed in crossing the Mediterranean — attempting to smuggle themselves into those erstwhile colonizers in search of a better life — find themselves confronted by anti-immigrant xenophobia and the “illegal alien” label.

Now, on top of everything, these people are bearing the brunt of the climate disaster — and all because of the greenhouse gases emitted by former colonial overlords that have enjoyed generations of abundance.

Who bears responsibility? In 2009, the capitalist countries of the Global North agreed to take responsibility with the Copenhagen Accord. They pledged to provide US$100 billion by 2020 to help the developing and low-income countries that have been suffering on the front lines of the climate crisis to build infrastructure and respond to the crisis.

In December 2020, the UN secretary-general pleadingly reminded those countries of what they had “promised.” Did he really believe they would honor their pledge from a decade earlier?

These are the so-called “democratic states” that elect new administrations. They include Italy, which recently selected an extremely fascist, outspokenly anti-immigrant and anti-Islamic prime minister, along with other European countries that are now lurching rightward one after another.

The next UN Climate Change Conference (COP27) is taking place in an Egyptian resort city. The same “democratic states” also furnished an alibi for a military dictatorship that has tortured, imprisoned, and executed pro-democracy figures since coming to power in a 2013 coup.

Inequality has been on the rise, even when we consider the domestic political situation in countries that at least have democratic controls in comparison with the “might makes right” world of international politics.

The so-called “yellow envelope law” is a concrete instance of what the climate justice marchers were talking about with their cries of “put people ahead of profits!” This would amount to very slightly widening the scope of what is considered a “lawful” strike by recognizing subcontractor employees and “specially employed” workers as “workers” and making the company that hires the subcontractors a party to negotiations (strangely enough, they aren’t at the moment).

But even this is unlikely to pass the National Assembly. When we can’t even overcome domestic inequalities through democratic politics, what hope do the citizens of the world today have of stopping the borderless climate crisis from barreling toward catastrophe? The climate disaster is already enveloping the Global South, and the wave is only gaining speed.

Along the way, we’ve gotten used to the fact that human beings are still in competition. We’re blithely living in comfort, even as we face the possibility that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine — where the use of nuclear weapons has recently been discussed — might end up escalating into a Third World War among imperialist powers. For all our tremendous advancements in science and scholarship and all our economic progress, our perceptions of war seem even more regressive now than they were in the late 18th century, when Immanuel Kant wrote “Perpetual Peace.”

What about our capacity for sympathizing with others’ suffering? One of the slogans of the animal rights movement today is “The question is not, Can they reason? Nor, Can they talk? But, Can they suffer?” Those words were written by Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th century.

Beyond this sort of poverty of awareness and loss of the ability to sympathize, we have found ourselves under the sway of arrogant technology advocates. The seeds of catastrophe lie as much within us as they do in the climate crisis.

If the material foundation of all of society’s superstructure lies in capitalism, there is no possibility that those in power will take any action that would be their own undoing. It’s axiomatic that they would allow themselves to be led by technology advocates who claim that it is possible to overcome the climate crisis. All that remains for us is the anger and protests of the world’s people — together with our solidarity with them, and our ability to take to the streets to put pressure on politicians.

We may have already missed our chance to avert catastrophe. I can only hope this sort of pessimism stems from my own lack of understanding. And I hope that we can overcome the capitalist regimes that have governed human systems of desire and values for centuries, ravaging nature without restraint, as we achieve an “ecological communal society” in which we respect other human beings and animals as we do nature.

Human history shows that nearly all self-directed uprisings by slaves (peasants or workers) have failed — and that even when they have succeeded, slavery doesn’t go away, but merely changes masters.

“Freedom or death!” is not merely a human rallying cry; it is also nature’s. Human beings may bow before the fear of death, but nature does not: it is merely destroyed.

Faced with the involuntary uprising of nature — destroyed by humans at a faster rate than it can be restored — the haves will hang on to the end, accepting themselves as part of nature and resisting, even if that means living like moles in bunkers hundreds of meters underground.

We now stand at the crossroads between that kind of dystopia and an ecological communal society.

Postscript: This piece was first published on Sept. 30, which was the closing date for a citizens’ petition to enact a “post-carbon law” in South Korea. At the time, the petition did not yet have the 50,000 signatures necessary to require National Assembly members to debate the legislation.

I hope that all of you reading this will do your part and encourage people you know to do so as well. Remember the famous axium — often attributed to Baruch Spinoza — that Koreans often read in middle school: “Even if I knew that tomorrow the world would go to pieces, I would still plant my apple tree.”

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?![[Column] Life on our Trisolaris [Column] Life on our Trisolaris](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0505/4817148682278544.jpg) [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

[Column] Life on our Trisolaris- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2[Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- 3Amid US-China clash, Korea must remember its failures in the 19th century, advises scholar

- 4New sex-ed guidelines forbid teaching about homosexuality

- 5[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- 6How daycares became the most viable business for the self-employed

- 7Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 8OECD upgrades Korea’s growth forecast from 2.2% to 2.6%

- 9Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 10[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art