hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

How daycares became the most viable business for the self-employed

In the competitive world of self-employment, which kind of business has the single highest rate of survival? Fried chicken restaurants? Coffee shops? Convenience stores?

According to an industry map for self-employed Seoul residents in 2014 by the city government-affiliated Seoul Credit Guarantee Foundation, the answer is child care, which had the highest rate of businesses founded in 2010 that were still operating two years later. It’s a survival rate of 95.7%, compared to the 63.3% average for all 43 business types examined.

One reason for the success is that unlike other businesses, child care providers receive government subsidies.

In an environment where free child care is being implemented across the board, day care centers certainly warrant establishment as a form of welfare facility. But the practical realities of child care in South Korea are such that many view the centers as a form of self-employment that guarantees at least a high chance of survival.

Recently, day care centers have been up in arms after a government announcement implementing “customized child care” as of July 1. The new terms restrict maximum day care center usage for children from single-earner households from 12 hours a day to six. The reduced child care subsidies for the “customized” group with restricted hours could translate into lower revenue for the centers.

Frictions between the government and day care centers over the subsidy issue happen almost every year. Parents are united in their disapproval, contending that there is a shortage of trustworthy child care facilities regardless of any policy changes.

A 40-year-old company employee surnamed Choi from a dual-income household has a daughter aged three years and two months. The girl is part of the “all-day” group at a day center in the family’s apartment complex, but can only use the facility from 10 am to 3 pm. The couple pays one million won (US$860) a month for a babysitter to take her to and from school. Their fear is that the daughter could end up treated as a nuisance by the center if they drop her off before work and pick her up afterwards.

“It doesn’t look much will change after they introduce customized child care,” Choi said. “It’s not as though the children who were with her before are leaving any later.”

While the group is classified as “all-day,” Choi said it was difficult to find any centers that actually provide all-day services.

A survey of 1,045 mothers of infants last year by the Korea Institute of Child Care & Education found 43.5% of them citing “the lack of trustworthy child care facilities during work hours” as their single biggest complaint in raising children.

“When I had the first one, we were 250 on the waiting list for the national and public day care centers we applied to,” said a 33-year-old mother currently on maternity leave with a two-month-old baby and another child aged 22 months. “We’re still at 180.”

The mother also said her child was still eighteenth on the waiting list at a private day care center she applied to three months ago.

While one day care center was available for immediate placement, the mother withdrew her child after just two days.

“There weren’t any safety bars on the slide, and the place was very cramped. It seemed unsafe,” she said.

Periodic news reports about abuse and accidents at day care centers have only fed the fears of parents.

The government child care budget for 2016 alone totals 10.5 trillion won (US$9 billion), yet the centers themselves complain of financial problems and parents remain dissatisfied.

“We have over 40,000 day care centers, yet parents talk about having nowhere to place their children and instructors have to deal with long hours and low wages,” said Woo Seok-jin, an economics professor at Myongji University.

“It’s a perverse situation where the government is spending massive amounts, yet nobody is sensing any effects from the policy measures.”

Relying on the private sector, hands off on quality control

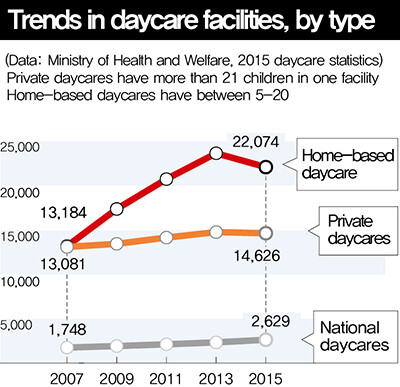

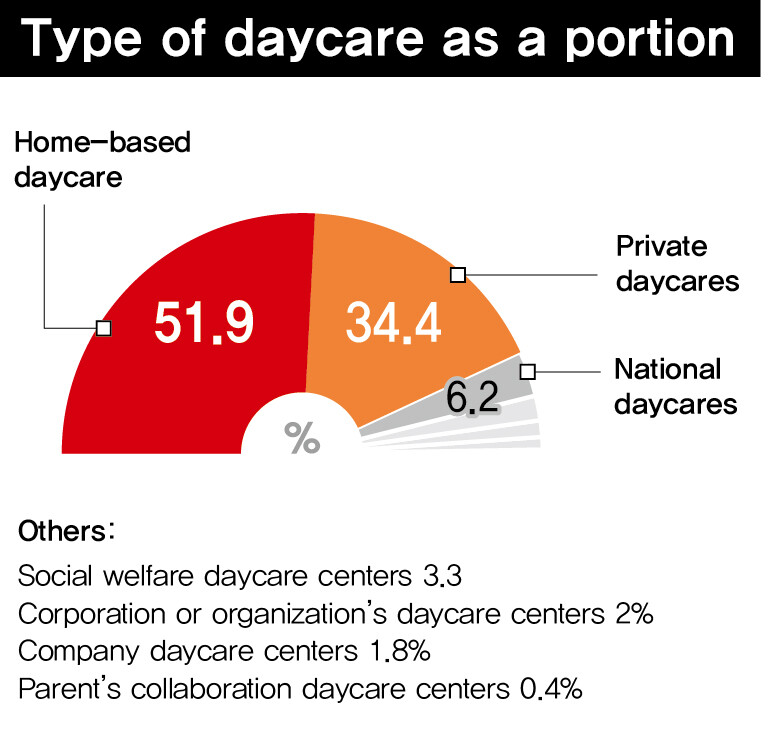

According to experts, the root cause of the current problem is a combination of the government’s reliance on the private market and its hands-off approach to coordinating day care facilities and managing quality. As of late 2015, South Korea had a total of 42,517 day care centers. National and public-affiliated centers accounted for 2,629, or just 6.2%. In contrast, 86.3% were private day care centers caring for 21 or more children (14,626) or “family day care centers” caring for 5 to 20 (22,074). It’s the result of an initial government policy approach of leaving matters to a private sector more capable of adding easy numbers rather than expending the effort to expand costlier national and public-affiliated center.

As of late 2014, the waiting list for national and public day care centers stood at 250,000 - a competition rate of over one in 100. In some regions, families have had to wait as long as three years. Parents prefer the nationally and publicly run centers for their quality of care. The facilities tend to be better, with additional support for instructor staffing costs and responsible oversight by the government.

Privately run centers, in contrast, are a crapshoot from one region to the next. For the private sector, the government only provides subsidies based on the number of children cared for. Not only is it less support than the nationally and publicly run centers receive, but when numbers dwindle, some of the centers end up barely scraping by. Their response is often to decrease pay to instructors and reduce meal stipends for children. A Ministry of Health and Welfare survey of child care conditions for 2015 showed average monthly salaries of just 1.44 million won (US$1,240) and 1.39 million won (US$1,200) for new instructors at private and family day care centers, respectively.

Desperate need for greater public service role from day care centersIf anything, the situation has gotten worse under the free child care policy. The South Korean government has implemented a policy of free child care for all income segments - starting with infants in 2012 and expanding to children up to five years old in 2013. Use of infant day care centers exploded as more and more parents worried they might be missing out. The number of home-based daycare centers - easily arranged by households living in apartments or standalone housing - jumped by 40% from 13,184 in 2007 to 22,074 last year. The number of births declined by 54,489 over the same period. The quality of child care appears to have declined amid growing day care center competition.

“In the past few years, per capita support for child care costs has basically remained frozen,” said Kim Hye-gum, a professor of child care studies at Dongnam Health College.

“Today, it’s not really clear whether day care centers are social welfare facilities or profit-oriented private enterprises,” Kim added.

Experts warn that the child care conflict could continue if the government doesn’t take steps to improve service quality and focus its policies on promoting the centers’ public service contribution.

“The government talks about free child care, yet its commitment to expanding nationally and publicly run day care centers remains weak and it says nothing about how it’s going to manage the oversupply of private centers,” said Nary Shin, a professor of child welfare studies at Chungbuk National University.

“Once ‘customized child care’ is implemented, day care centers are likely to try to squeeze out a profit and maintain the status quo somehow as their revenues drop,” Shin predicted.

Lee Sang-goo, co-representative of the group Welfare State Society and a specialist in preventative medicine, suggested an approach of increasing the percentage of children attending nationally and publicly run centers by 30%.

“We also need to promote the public service role of private day care centers with strict assessment and certification, while drastically increasing government support to those that achieve certification and introducing with parents as steering committee members, and an oversight officer,” Lee suggested.

By Hwangbo Yon and Lee Jae-uk, staff reporters

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0517/8117159322045222.jpg) [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later

[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later![[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/7417158465908824.jpg) [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence- [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

- [Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- [Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- [Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- 2S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 3[Exclusive] Unearthed memo suggests Gwangju Uprising missing may have been cremated

- 4[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner t

- 5China, Russia put foot down on US moves in Asia, ratchet up solidarity with N. Korea

- 6Xi, Putin ‘oppose acts of military intimidation’ against N. Korea by US in joint statement

- 7Truth commission confirms Korean War killings by soldiers and police

- 8[Editorial] South Korean women are mobilizing in unprecedented ways

- 9Calls for gender-equality continue as demonstrations target President Moon

- 10[Column] “Hoesik” as ritual of hierarchical obedience