hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

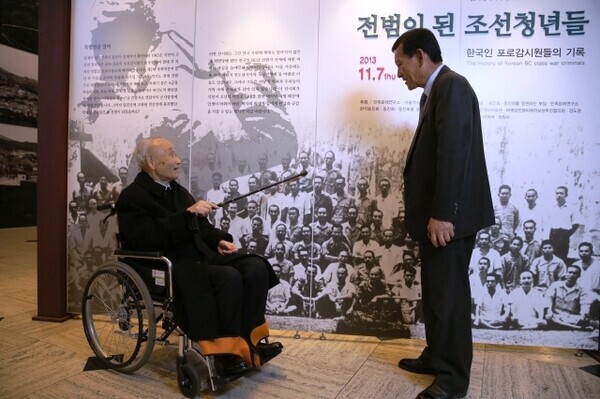

Last Korean war criminal in Japan dies

The last surviving Korean Class-B/Class-C war criminal from World War II, Lee Hak-rae, died on Monday at the age of 96.

His obituary began with a short sentence: "I have some sad news to relate."

The obituary was posted on Facebook on the afternoon of Sunday by Konosuke Fujii, who runs the East Wind Bookstore in Ikaino, a neighborhood largely populated by Zainichi Koreans in Osaka, Japan.

"Lee hit his head and broke his leg in a fall at his home on March 26. He was taken to the hospital for treatment but passed away at 2:10 pm on March 28. Until his last moment, Lee kept thinking about his deceased colleagues and trying to pass legislation [to provide relief for Class-B/Class-C war criminals]. That legislation was blocked by the administration of Shinzo Abe," Fujii wrote, referring to Japan's former prime minister.

Fujii explained that Lee's life was dominated by his struggle against the injustice of the Japanese state.

Lee was born in Boseong, South Jeolla Province, in 1925, the first of three children. In the spring of 1942, the mayor of his township unexpectedly asked him to come by.

"They're recruiting prison guards for prisoner-of-war camps in Southeast Asia, and you should sign up," the mayor told him, explaining that the job would last for two years and pay 50 won per month.

Aged 17, Lee submitted an application, thinking that two years of hard work would be worth it if it kept him out of forced labor and conscription, which was supposed to begin soon. On Aug. 19, 1942, Lee boarded a ship in Busan bound for Southeast Asia.

Three years later, after Japan's defeat in the war, Lee was sentenced to death by an Australian military tribunal for abusing Allied prisoners. That death sentence marked the beginning of a life of pain.

After beginning the Pacific War in December 1941, Japan enjoyed a string of victories in Southeast Asia, but its offensive also netted hundreds of thousands of Allied POWs. The Japanese government recruited 3,012 Korean young people to watch over the POWs.

Lee was assigned to Thailand, where the Japanese army subjected the POWs to brutal labor without adequate food, medicine, or even clothing. The POWs were put to work building the Thai-Burma Railway, which was famously portrayed in the 1957 film "The Bridge on the River Kwai."

Countless POWs lost their lives because of the intense labor required to build railroad lines on precipitous cliffs. As Lee, a prison guard, tried to arrange the work crews demanded by the Japanese military engineers, he often had spats with Colonel Ernest Edward Dunlop, an Australian medic. That's how he ended up with the terrible stigma of being a war criminal after the war.

“The Korean Youth Who Became a War Criminal”Despite being a mere pawn in the war Japan was waging, 129 Korean prison guards were found guilty of abusing POWs in war crimes tribunals organized by the Allies. Of that number, 14 were sentenced to death and executed.

Lee's death sentence was commuted, sparing his life, but he soon would face the merciless opprobrium of society. Koreans denounced him and others like him as "Japanese collaborators," while the Japanese reviled them as "war criminals."

Lee was stripped of his Japanese citizenship by the Treaty of San Francisco, which took effect in April 1952. After that, the Japanese government refused to give Korean Class-B/Class-C war criminals the aid provided in postwar legislation. Along the way, two other war criminals ended their own lives, unable to endure the misery: Heo Yeong in 1955 and Yang Wol-seong in 1956.

Running out of options, Lee joined around 70 other Korean Class-B/Class-C war criminals to set up a group called Dongjinhoe, which means "moving together," in April 1955. Members of the group began pushing the Japanese government to pay compensation and provide relief.

But when South Korea and Japan concluded their treaty on basic relations in June 1965, Japan halted dialogue with Dongjinhoe, claiming that the treaty had resolved all outstanding disputes.

It was infuriating for Lee to be treated like a Japanese when it came to war crimes, but like a Korean when it came to compensation.

Lee and his colleagues had no choice but to launch a legal battle. A lawsuit that they filed in the Tokyo District Court on Nov. 12, 1991, dragged on for five years. In its ruling on Sept. 9, 1996, the court acknowledged the need for the plaintiffs to be compensated but rejected their suit, concluding that "this is a matter of the state's legislative policy."

That view was echoed in decisions by a high court (July 13, 1998) and by Japan's Supreme Court (Dec. 20, 1999). Despite these setbacks, Lee tried not to lose heart.

"All of my other colleagues died while we were dealing with these difficulties. As the youngest, I was the only one to survive," he said.

For a brief moment in May 2008, it seemed as if the issue might be resolved after all. That's when Japan's Democratic Party, then in opposition, drafted a bill that would have paid 3 million yen (US$27,290) in compensation to each of the Korean Class-B/Class-C war criminals in May 2008. For Lee, who had enjoyed success in the taxi industry, the money itself wasn't important.

As expected, the bill was ignored by most lawmakers and eventually scrapped. When the Democratic Party came to power, they no longer paid any attention to Lee and his colleagues' suffering.

In April 2015, on the 50th anniversary of South Korea and Japan's normalization of diplomatic relations, Lee spoke with a reporter at the Japanese Diet. "I really hope this issue will be resolved this year," said the 90-year-old man, as he tried not to sob.

In 2017, Lee's memoirs, titled "The Korean Youth Who Became a War Criminal," were published by the Center for Historical Truth and Justice. In his memoirs, he asked the Japanese government to "correct its irregularities and quickly draft a bill that gives serious consideration to judicial calls for legislation."

In February 2020, Lee attended a lecture in Nishitokyo, a city in the metropolis of Tokyo, where he once again spoke in support of legislation. But no bill was submitted during the regular session of the Diet because of the COVID-19 pandemic, among other factors.

Thus it was that time was frittered away as South Korea-Japan relations sunk to a new low. In the end, Lee died before he could gain the remedy he'd sought for so long.

By Gil Yun-hyung, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 3‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 4Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 5[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 6[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 7[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 8[Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- 9Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 10Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US