hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

S. Koreans in 30s, 40s are shelling out 30% of disposable income to pay back loans

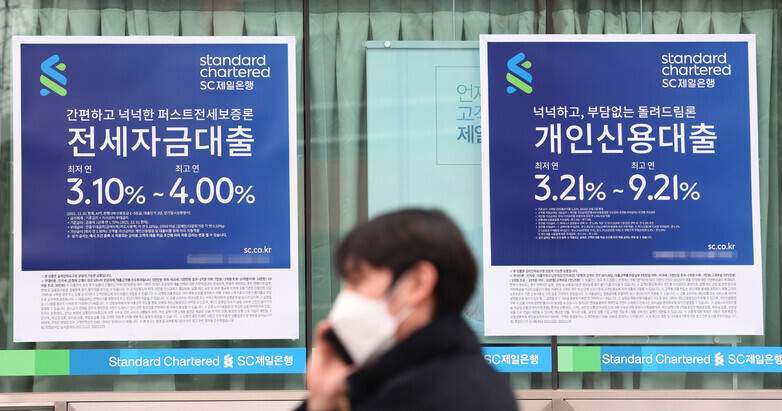

South Korea’s commercial banks have recently been competing to offer more household loans. They’ve been lowering loan interest rates and increasing limits, using methods like lower spreads and special rates.

From the banks’ standpoint, more lending translates into more profits, so long as they don’t find themselves getting bilked out of their funds or their payments going into arrears. With household loans dropping for three straight months between January and March, they’ve been getting proactive about their lending.

According to data from the Bank of Korea (BOK) and Financial Services Commission (FSC), household loans across all financial sectors fell by 700 billion won in January, 300 billion won in February, and a full 3.6 trillion won in March.

Financial oversight authorities had made the decision to restrict this year’s rate of increase in household loans to no more than 4%–5% — but with loans declining at this rate, they have not been interfering at all with banks’ efforts to court borrowers.

Principal and interest burden rate already upwards of 30%The decrease in household loans hasn’t been caused by a drop in mortgage loans. Indeed, those loans showed month-on-month rises of 2.9 trillion won in January, 2.6 trillion won in February, and 3 trillion won in March.

The biggest dip has been in the category of “miscellaneous loans,” which mainly consist of credit loans. That area is what has been driving the overall decrease in household loans. In March, miscellaneous loans were down by no less than 6.6 trillion won from a month earlier — meaning that there were a lot of repayments.

As reasons for the drop, the FSC has been pointing to rising loan interest, increased regulations on debt service ratios (DSRs) for individual borrowers, and a slowdown in housing transaction volumes.

Rising interest rates in particular have been increasing the incentive to save and reducing the incentive to take out loans. Market rates have been driven up substantially by a combination of inflation and three separate BOK hikes of the benchmark interest rate, following a Monetary Policy Board decision last November.

While March indicators have not yet been shared, BOK figures on trends in financial institutions’ weighted average rates for February showed household loans in the banking sector (for newly handled amounts) hitting a rate of 3.93%. That represents a 1.14-percentage point jump from the per annum rate of 2.79% in December 2020.

A steep rise in household loans has the potential to send shock waves through the financial system. A case in point was the credit card crisis of 2003–2004. Companies had been issuing cards willy-nilly, and customers ramped up their usage, robbing Peter to pay Paul as they used one card to repay their bill on another.

By 2003, the default rate for credit card usage was close to 30%. At one point, more than four million South Koreans were deemed “delinquent borrowers” for failure to pay their credit card bills on time.

Once the credit card crisis was resolved, household loans started rising again, this time in tandem with an increase in mortgages. As of late 2021, the household credit balance (including household loans and sales on credit) totaled 1.862 quadrillion won. Eight years earlier in late 2013, the level had been 1.019 quadrillion won — meaning an increase of 843 trillion won, or an average annual increase of 10.4%.

Warning bells have been sounded repeatedly over the risks associated with a rise in household debt. But since the delinquency rate for household loans was not all that high, those warnings never led to any drastic measures.

So will we be able to shake off all our fears if the rise in interest rates translates into a slowdown in the rate of increase in household loans?

The answer is not so simple. That’s because quite a few households stand to suffer a heavy blow while interest rates are rising, if only because of the sharp rise in debt that came before.

Households that have a lot of financial assets have less to worry about, since they get to enjoy an increase in interest earnings from those assets. Some of them might sell off the assets to pay back their loans.

But households with a lot of net debt are poised to bear the brunt of the interest hike.

The Survey of Household Finances and Living Conditions, which has been jointly conducted since 2010 by Statistics Korea, the Financial Supervisory Service, and the BOK, allows us to trace how the debt burden has changed for South Korean households.

A look at principal and interest repayment as a percentage of household disposable income shows a rise from 19.5% in 2012 to 25.3% in 2020.

The repayment percentage had actually soared as high as 26.6% in 2015 before falling back down 3.9 percentage points to 22.7% the following year. That year, financial oversight authorities restructured household debt, introducing “safe conversion loans” that applied installment-based repayment for loans that were in their grace period or were scheduled for a bullet payment.

But afterwards, the percentage of principal and interest repayment relative to disposable income began climbing once again.

By age group, households headed by people in their 30s and 40s have been struggling under very high repayment burdens. For those in their 30s, the rate passed 30% for the first time in 2018 at 32.6%; by 2020, it was all the way up to 34.8%.

For those in their 40s, the rate passed the 30% mark in 2020 at 31.6%. Not only did household debt increase substantially in 2021, but the rate was driven up further by the rise in interest rates.

Starting this year, financial oversight authorities have introduced regulations barring individual borrowers from having a DSR above 40% for banks (50% for non-banking financial companies). But if the average for all households exceeds 30%, that means quite a number of households are already approaching the 40% mark.

The biggest variable threatening households that have taken out many loans is the specter of a steep dive in the price of the residence they have used as collateral. In the event of a race to sell off housing — by borrowers repaying their loans, or by financial companies recovering them — they would face inevitable catastrophe.

But it’s difficult to predict exactly which straw will break the camel’s back. The brakes need to be put on the climbing debt before that happens.

Debt combines with growing interest burdenEven if we manage to avert disaster, can we avoid the economy getting mired in a domestic demand slump as the repayment of household debt cuts into the wherewithal to consume? In 2017, researchers Shim Hye-in and Ryu Doo-jin published a paper titled “Household Debt and Domestic Consumption: An Empirical Analysis and Associated Financial Policy Implications” in the Korean Journal of Financial Studies (Vol. 46, No. 1).

Their findings showed that while household debt can potentially drive up consumption as it eases liquidity restrictions and increases financial assets, a large rise in household debt cuts into consumption as the household repayment burden is exacerbated.

In reality, slack domestic demand has long since become an entrenched part of the South Korean economy. Not once in the period from 2005 to 2017 did the rate of increase in private consumption exceed the overall economic growth rate.

Thanks to factors such as a big hike in the minimum wage, nominal wages did increase sharply in 2018, with the rate of increase in private consumption reaching 3.2%. It was the first time in 13 years that the rate was higher than the economic growth rate (2.9%).

But it only lasted a year. The rate of increase in consumption has since slipped back down below the growth rate, amid factors that include the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Turning back the tide now appears to be more difficult than ever. With housing prices rising sharply, those households that spent money up front to buy homes will eventually have to tighten their belts once again under the interest payment burden.

By Jeong Nam-ku, editorial writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 2Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors

- 3Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 4Noting shared ‘values,’ Korea hints at passport-free travel with Japan

- 5AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 6Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US

- 7‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 8Exchange rate, oil prices, inflation: Can Korea overcome an economic triple whammy?

- 9Terry Anderson, AP reporter who informed world of massacre in Gwangju, dies at 76

- 10[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel