hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Hidden history of S. Korea’s Blue House: A supreme seat of authority rooted in Japanese colonial rule

“As of today, the era of the Blue House presidency is over.”

These words, spoken by outgoing President Moon Jae-in before a crowd of people seeing him off on his last day of work at the Blue House on Monday, sounded like a weighty declaration.

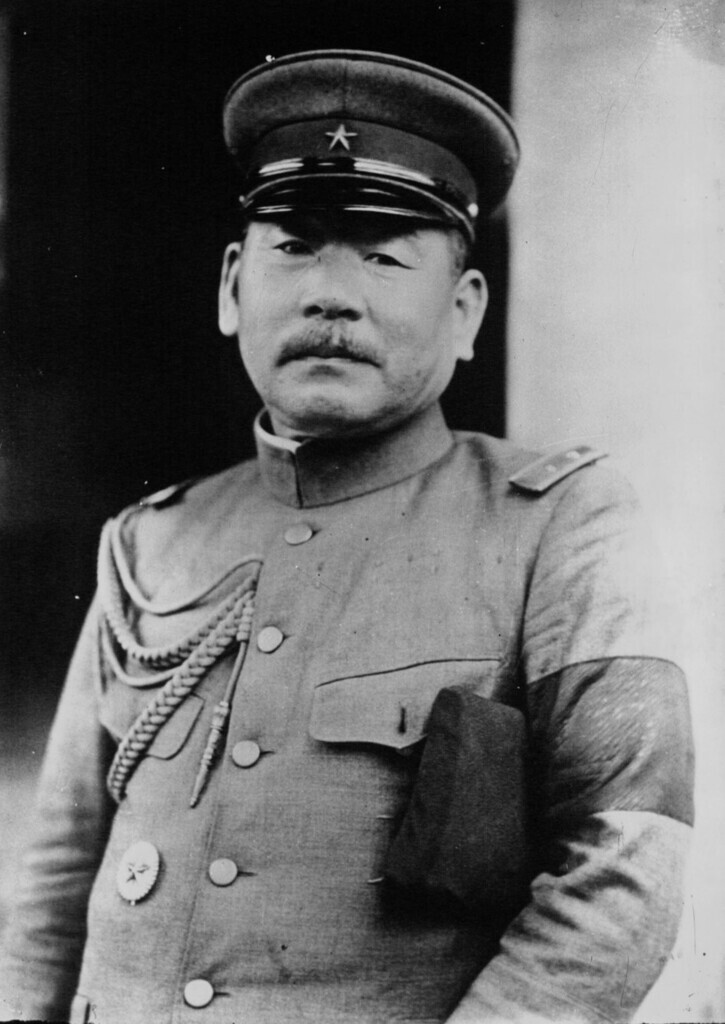

It signified the end of the Blue House’s history dating back 83 years (or 82 years and eight months, more precisely) as the supreme seat of South Korean authority — ever since Sept. 20, 1939, when Jiro Minami (1874–1955), the seventh Japanese governor-general of Korea and a figure notorious for his policy forcing Koreans to adopt Japanese names, moved into a new residence built in the rear garden of the Gyeongbok Palace, the primary palace used by Joseon’s kings.

In September 1939, what would develop into World War II had just broken out, with China ramping up its counterstrike in the Second Sino-Japanese War and Germany carrying out its invasion of Poland. At a time when the biggest issue was the unstable global situation, contemporary news outlets did not devote major coverage to the construction of a new residence by the governor-general of Korea.

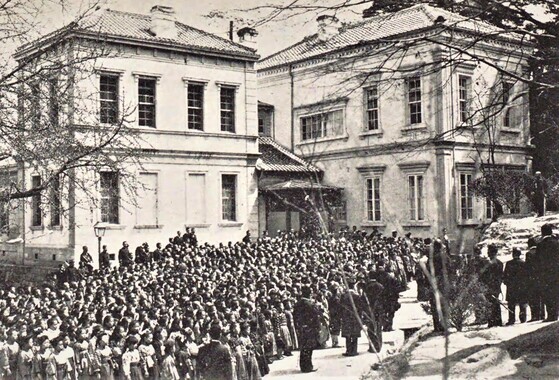

Page 2 of the Dong-A Ilbo newspaper’s edition on Sept. 21, 1939, shows an article and a photograph concerning the inauguration ceremony of the governor-general’s residence. Officials known as “shinkan,” who had been sent from Japanese shrines, can be seen holding a prayer ceremony, dressed in white as they hang amulets at the building’s entrance; behind them, officials from the Japanese colonial government lower their heads respectfully.

The article next to the photograph explains that the new governor-general’s residence was built over a two-year period and cost 480,000 won. The splendid inauguration ceremony, it says, was held at 11 pm on Sept. 20, with Minami in attendance alongside the government’s second-in-command, Political Affairs Superintendent Rokuichiro Ono, and various department directors. It goes on to say that Minami and his wife were scheduled to move into the new residence and complex two days later, on Sept. 22, along with a secretary identified by the surname Goto and his family.

It was the Chosun Ilbo that got tongues wagging about the new residence. A mere 10 days after Minami moved in, the newspaper published a front-page exclusive on Oct. 3 on a visit to the new structure.

This was at a time when Japan had become more direct about its forced mobilization policies conscripting Koreans to serve as soldiers and workers for its war effort. Written to congratulate Minami on moving into his new residence, the main article was titled “Solemnly spending a healthy day at the Blue House pine forest”; a subtitle read “A visit to see a veteran governor-general’s new residence.”

The article describes the view inside of the Blue House — then known as the “Gyeongmudae,” or “capital pavilion” — and the scenery in Gyeongseong (Seoul) visible from the structure, along with the conversation shared during a visit by Chosun Ilbo President Bang Eung-mo and Editor-in-Chief Lee Hun-gu, who came bearing a gift of fruit to congratulate Minami on the move.

According to the article, the “rosy-cheeked, gray-haired” Minami greeted the visitors “as vigorously as always,” showing them around the hiking trails on the foothills of Mount Bugak in the rear, a garden with rare plants and stone lanterns, and a pond with frolicking goldfish and carp brought over from Jinhae.

“The governor-general then guided us toward the foothills in back, explaining that he wanted to show the inside of the precincts,” it continued. “As we went around past the garden and up over the viaduct toward the foothills, we saw the Korean buildings behind the Gyeongmudae had been rebuilt all around. [. . . ] We went up on the hexagonal pavilion and saw a quite beautiful view, where the area north of Mount Nam sprawled out across a pine forest that was like a sea of trees.”

While many people tend to overlook this, the governor-general’s construction of the Japanese General Government Building was the decisive factor in the origins of the Blue House as a seat of power.

After Gyeongbok Palace was sealed off and the complex housing the government-general of Korea was completed in 1926, there were continued issues with the governor-general’s long commuting distance from his Waeseongdae residence in Namchon near the Hyehyeon neighborhood, along with inconveniences related to security.

The decision to relocate was made in the mid-1930s, but construction kept being delayed. It finally began in 1937, after Minami took over as governor-general, and after being halted once in 1938 due to wartime economic controls and a shortage of items due to the war between Japan and China, the new residence was eventually inaugurated on Sept. 20, 1939, with a traditional Shinto prayer ceremony attended by Japanese shinkan officials.

The residence was built in the symbolic setting of Gyeongbok Palace, which had been Korea’s primary palace and was associated with the dignity and elegance of the Joseon dynasty that had lasted for 500 years. Yet even backed by the threats of the gun and sword, imperial Japan’s force did not immediately win the day.

It’s worth reflecting on the fact that the Blue House was completed in 1939, shortly after Japanese private residences and offices such as the hospital of Keijo Imperial University had definitely taken up residence in the neighborhoods of Seochon and Bukchon next to the Japanese Government General Building. In other words, this was just six years before Korea’s liberation.

That means the symbolic establishment of complete control over Korea in spatial terms was only completed six years before Korea was freed from Japanese hands. In that sense, the Blue House is significant as historical evidence attesting to how long it took for imperial Japan to symbolically “seize” this space.

Kuniaki Koiso and Nobuyuki Abe, Minami’s successors as governor-general from 1942 to 1945, resided there when they discussed and implemented policies of forced mobilization and exploitation amid Japan’s last desperate struggles — including their orders for conscription and the provision of workers and goods and their mobilization of women’s volunteer corps. The official residence and the Japanese military command in Yongsan were the two main bases for Japan’s plundering and pillaging of the Korean Peninsula.

Minami, a former commander of the Japanese forces in Korea, also used the Yongsan military command (watched over by his subordinates) as a base for his rule. In effect, the governor-general’s residence and the command were part of a single whole.

The same residence was used by Gen. John Hodge, commander of the US Army Forces in Korea — after the departing Governor-General Abe had set fire to its fixtures in the wake of liberation, that is.

Rhee Syngman would later move in, and after the Korean War erupted, Kim Il-sung stayed at the Blue House during three visits to Seoul after North Korean forces had occupied the city within three days of the war’s start.

However, according to what Rhee Syngman's wife Francesca confided to acquaintances during her lifetime, Kim Il-sung hardly touched the interior furniture or fixtures.

In a memoir published in 2016, Paik Sun-yup (1920-2020), who served as South Korea’s Army chief of staff, explained that, given that Kim Il-sung assumed Gyeongmudae would soon belong to him, it would be reasonable to assume he would have cherished and wanted to preserve the place as best as possible.

Later, in 1968, the North Korean regime sent special forces to raid the Blue House, but failed. The intensified conflict between the two Koreas made the official presidential residence an iron fortress of power that was disconnected from the public.

These secret histories remind us that the history of the Blue House was not just concerned with the history of successive presidents, but rather the difficult modern history of the Korean Peninsula that started with the Japanese occupation and invasion and led to the era of a divided Korea.

By Roh Hyung-suk, culture correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 4No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 5Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 6US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters

- 7[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 8[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 9Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 10Samsung subcontractor worker commits suicide from work stress