hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

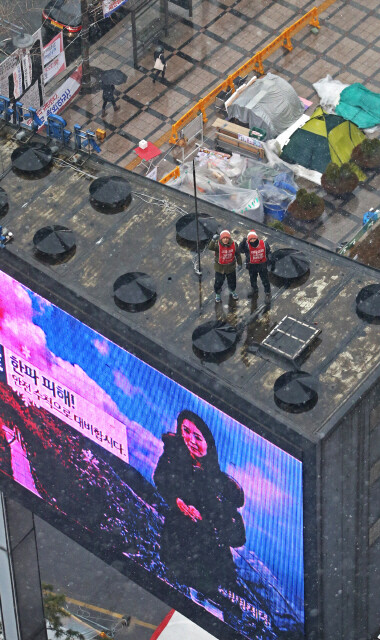

[Analysis] Aerial protests the last battleground of aggrieved workers

Aggrieved workers continue to climb structures and equipment for aerial protests. When no one is listening, going up becomes the only option they see to make their voices heard down below. Like climbing vines, the workers quietly ascend everything from factory smokestacks to high-voltage electricity transmission towers and downtown lighting displays.

December 15 marked 202 days since Cha Gwang-ho climbed a smokestack in Kumi, South Gyeongsang Province. The former Star Chemical worker lost his job in the company’s division sale.

It was also the 34th day of protests atop an electronic display in front of the Seoul Press Center by Kang Seong-deok and Im Jeong-gyun, two employees of subcontractors for Cable and More. They are calling for the full reinstatement of 109 workers that the company refused to keep on when it changed subcontractors because of their union worker status.

And it was the third day of a protest by dismissed Ssangyong Motor workers Lee Chang-geun and Kim Jeong-wook, who climbed a 70-meter smokestack in Pyeongtaek, Gyeonggi Province after their reinstatement was blocked by a Supreme Court ruling finding the automaker’s layoffs valid.

The aerial protest has become the last battleground for aggrieved workers with nowhere else to turn. The rules of the practice in South Korea date back to the dark days of Japanese colonization. The first known case came on May 28, 1931, when Kang Ju-ryong, a 31-year-old worker at the Pyongwon Rubber Factory in Pyongyang climbed up on the rooftop of the city’s famed Ulmildae pavillion to demand a rollback of wage cut. “I have come up on this room prepared to die, and I will not come down until the president of Pyongwon Rubber comes here to declare the wage cuts canceled,” she said at the time. Even after receiving a promise to cancel the cuts, Kang continued fighting to overturn the dismissals of striking workers.

Numerous other workers have carried on the tradition started by Kang, including Kim Ju-ik and Kim Jin-suk of Hanjin Heavy Industries and Construction (HHIC); Choi Byeong-seung and Cheon Ui-bong of Hyundai Motor; Han Sang-gyun, Moon Gi-ju, and Bok Gi-seong of Ssangyong Motor; Lee Jeong-hun and Hong Jong-in of YPR; and Yeo Min-hui and Oh Su-yeong of JEI. It’s a lineage that stretches 83 years to the five workers protesting on Dec. 15, 2014. Each name, experts said, is a painful testament to a lack of communicativeness by a state that is friendly to business and hostile to labor.

“Workers who feel they can’t trust the official state system, and who think even the courts won’t protect them, are being driven to choose unconventional means of fighting back,” said Hanyang University professor Lim Sang-hoon, who heads the labor and society committee for the group People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy.

A lack of safeguards has made some workers lose their jobs overnight, and that has driven them to aerial protests.

“The signal the state sends when it tells employers that they should ‘enforce law and order’ is that they should never compromise, and that they’re free to lay people off and hire indirectly as they see fit,” said Cho Don-moon, a sociology professor at the Catholic University of Korea.

“Without any other alternatives, workers keep finding themselves cornered into making the worst possible decisions,” Cho explained.

Even the briefest attention to the complaints of the aerial protests is enough to reveal the issues most in need of resolution. Most are calling for the same things the Ssangyong smokestack protesters are: stronger conditions for layoffs and reinstatement of their old jobs. In June 2003, HHIC committee leader Kim Ju-ik went up on the No. 85 crane at the Yeongdo shipyard in Busan to demand reinstatement of laid-off workers. Eight years later in 2011, it was Kim Jin-suk, a committee member for the Busan office of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions, who ascended the same crane for a 309-day protest to demand cancellation of the company’s layoffs. Kim’s protest resulted in a high-profile show of support as visitors boarded “Hope Buses” to travel to the site.

Two other reasons for the workers’ dangerous decisions are demands for labor union recognition and a ban on union suppression. Chapter heads Hong Jong-in and Lee Jeong-hoon enlisted “creative consulting” support in an aerial protest from 2012 to this year to demand a halt to YPR union suppression and punishment of the company. Investigator and courts remained unmoved. Workers at JEI staged a 202-day protest to demand reinstatement of laid-off workers and basic labor rights, including a return to the old collective bargaining system.

A third running theme is illegal dispatch work. It’s the labor situation where the helplessness of state authorities is most apparent. Choi Byeong-seung and Cheon Ui-bong, two Hyundai Motor subcontractor workers, held a 296-day protest on an electricity transmission tower to demand punishment of the company for its illegal practices, and courts have found four makers of finished cars - Hyundai Motor, Kia Motors, Ssangyong, and GM Korea - to be guilty of illegal dispatch labor. Yet no one at any of the companies has been held criminally liable to date, and none of the workers have been granted their legally entitled full-time positions or received the difference in pay.

By Jeon Jong-hwi and Kim Min-kyung, staff reporters

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China? [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/9317135153409185.jpg) [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?![[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0419/2317135166563519.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK- [Editorial] Does Yoon think the Korean public is wrong?

- [Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- [Guest essay] Amending the Constitution is Yoon’s key to leaving office in public’s good graces

- [Editorial] 10 years on, lessons of Sewol tragedy must never be forgotten

- [Column] A death blow to Korea’s prosecutor politics

- [Correspondent’s column] The US and the end of Japanese pacifism

- [Guest essay] How Korea turned its trainee doctors into monsters

- [Guest essay] As someone who helped forge Seoul-Moscow ties, their status today troubles me

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The clock is ticking for Korea’s first lady

- 2After 2 months of delayed, denied medical care, Koreans worry worst may be yet to come

- 3Hong Se-hwa, voice for tolerance whose memoir of exile touched a chord, dies at 76

- 4[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 5[Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

- 6Samsung barricades office as unionized workers strike for better conditions

- 7All eyes on Xiaomi after it pulls off EV that Apple couldn’t

- 8[Editorial] As it bolsters its alliance with US, Japan must be accountable for past

- 9[News analysis] After elections, prosecutorial reform will likely make legislative agenda

- 10US overtakes China as Korea’s top export market, prompting trade sanction jitters