hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Analysis] For S. Korea, getting nukes would lead to pariah status

On Feb. 15, Saenuri Party (NFP) floor leader Won Yoo-cheol argued that South Korea should acquire nuclear weapons and long-range missiles in the interest of national security, in a speech on behalf of his party in the National Assembly. This means that support of South Korea’s nuclear armament, which has been occasionally made by the far right, is now being openly voiced in the political mainstream.

Since this was an official speech in the National Assembly by the floor leader of the party in power, it is likely to provoke a major backlash both inside and outside of the country.

The idea of South Korea acquiring a nuclear arsenal not only is unrealistic given the reality of international politics but is also a reckless and self-destructive proposal that would take a huge toll on the country in the areas of the economy, foreign policy, and security.

“In his speech, Won Yoo-cheol was saying he wanted to go down the path of North Korea. If South Korea pursues nuclear armament, it will become an international pariah and be hit with sanctions just like North Korea and will suffer severe economic damage,” said Lee Geun, a professor at the Graduate School of International Studies at Seoul National University.

Will South Korea scrap its alliance with the US?

In order to make nuclear weapons, it is necessary to either produce weapons-grade uranium (enriched to 90%) or to reprocess plutonium. But South Korea is banned from reprocessing plutonium or enriching its own uranium even for peaceful purposes, let alone producing weapons-grade uranium.

Those conditions are outlined in the nuclear power agreement that South Korea made with the US, which is its only ally. Washington made a big push for the agreement, and Seoul had no choice but to accept it. The US did not even grant permission for pyroprocessing (a technology for reprocessing nuclear fuel), which the administrations of President Lee Myung-bak (2008-2013) and Park Geun-hye had sought during their negotiations to revise the agreement. The US did grudgingly allow South Korea to undertake electrolytic reduction, which is the first stage of research in this direction.

In the end, despite nearly five years of negotiations, South Korea failed to gain permission from the US for enrichment and reprocessing for peaceful purposes in the first revision of the nuclear agreement in 42 years.

During the signing ceremony for the revised nuclear agreement that was held in Washington on June 15, 2015 with South Korean Foreign Minister Yun Byung-se, US Energy Secretary Ernest Moniz said that the US is a strong proponent of the goal of denuclearization, reiterating American opposition to South Korean enrichment and reprocessing.

The revised nuclear agreement took effect on Nov. 25, 2015.

In order to undertake nuclear armament, South Korea would have no choice but to scrap its nuclear agreement with the US. “For South Korea to back out of its nuclear agreement with the US would signify the end of its alliance with the US. I really don’t know if the people who are calling for nuclear armament have any idea what that would mean,” said Kim Yeon-cheol, a professor at Inje University.

Do they want to be an international pariah?

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, which has 189 member states, including South Korea, strictly forbids the possession, development and transfer of nuclear weapons. According to the treaty, the only countries that are permitted to possess nuclear weapons by international law are the five permanent members of the UN Security Council: the US, Russia, China, the UK and France.

India, Pakistan and Israel are also de facto nuclear weapon states, but none of them ever joined the NPT. In addition, the US, China and other nuclear powers effectively tolerate these three countries’ nuclear arsenals. They are in quite a different position from North Korea, on which the UN Security Council continues to slap sanctions.

North Korea became a signatory to the NPT on Dec. 12, 1985, but it announced its withdrawal from the treaty on Mar. 12, 1993, at the height of conflict with the US, and it has never rejoined.

South Korea became the 86th country to formally ratify the NPT on Apr. 23, 1975, during the administration of President Park Chung-hee (1961-79).

Members that have ratified the NPT must also abide by International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) nuclear safeguards, which involve allowing agency inspectors to confirm that nuclear fuel is not being appropriated for military purposes.

While the NPT strictly forbids the possession of nuclear weapons, it acknowledges that reprocessing and enrichment for peaceful purposes fall under the sovereignty of the state. But South Korea has abandoned even this right through its atomic energy agreement with the US and the joint statement about denuclearizing the Korean Peninsula.

If South Korea moves to arm itself with nuclear weapons, it would inevitably be sanctioned by the international community for violating the NPT. If it became known that South Korea had appropriated nuclear materials for military purposes, the UN Security Council would adopt a resolution against it, just as it did against North Korea, and South Korea would suffer economic, diplomatic and military sanctions. South Korea would become a pariah state.

Given that South Korea is 99.5% dependent on foreign trade (according to 2015 figures by the Bank of Korea), it would be completely impossible to maintain the current standard of living amid international sanctions.

In 1968, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution No. 255 in order to maintain and strengthen the nonproliferation regime, in which it promised that the UN would intervene and protect non-nuclear weapon states that were attacked by nuclear weapon states. And during a special UN session on disarmament in 1978, the five nuclear powers promised not to launch a nuclear strike on non-nuclear weapon states. The former measure is referred to as active security, and the latter as passive security.

Prepared to withstand major long-term blackouts?

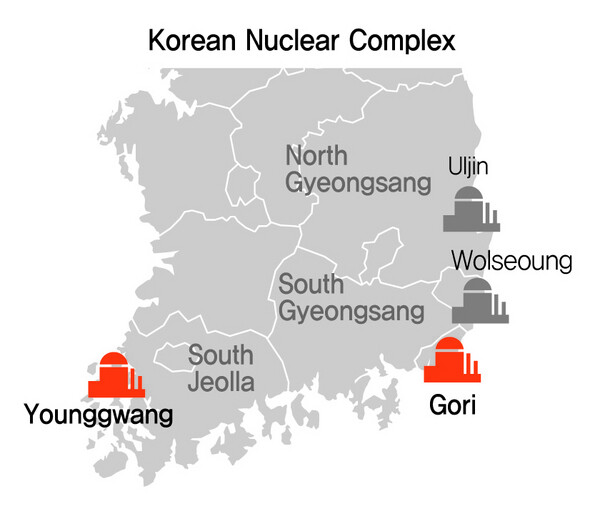

South Korea is an energy-poor country that relies on other countries for 96-97% of its energy resources. Its 23 nuclear power plants account for 30% of its energy needs, according to a 2015 atomic energy white paper. It’s also a big energy consumer, ranking fourth in the world for reliance on nuclear energy and tenth for total power consumption. That mixture - short on energy resources, long on consumption - is the country‘s reality today.

It’s also a situation that poses nuclear armament as a potential source of catastrophe. All of South Korea’s uranium imports are used in nuclear power plants. Ore is purchased from France and processed into slightly enriched form in the US before use in the plants. Nuclear armament would leave the country unable to import any more slightly enriched uranium for power plant use; doing so would result in sanctions from the international community for violation of the NPT and the IAEA Safeguards Agreement. The international market for uranium is strictly controlled, since even the slightly enriched form is a strategic material that a motivated party could convert to highly enriched form for use in nuclear weapons development. In other words, it’s not just another product that can be bought by anyone with the money for it. There‘s a reason all of the countries with nuclear development programs - including North Korea, India, Pakistan, and South Africa - also happen to be rich in uranium deposits.

If slightly enriched uranium did become impossible to import, it would send to a halt the nuclear power plants that shore up 30% of the country’s energy consumption. A society that is already sent into panic by even temporary large-scale blackouts in the summertime would have to deal with the same problem on a chronic basis. Proponents of nuclear armaments seem unlikely to throw their weight behind the anti-nuclear movement‘s calls for abandoning nuclear power to develop environmentally friendly resources instead.

Dark shadows of nuclear development

In 2004, early in the administration of President Roh Moo-hyun (2003-2008), South Korea nearly found itself sanctioned by the US and UNSC over an incident involving nuclear material.

During preparations for monitoring according to the IAEA’s Additional Protocol, it was learned that experiments had been conducted with a small quantity (0.2 grams) of weapons-grade highly enriched uranium (90%) at a laboratory in the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute (KAERI) in Daejeon’s Daedeok Research Complex in early 2000, and with the extraction of small quantities of plutonium at the Korea Institute of Science and Technology (KIST) in Seoul in 1982. The IAEA was outraged, and South Korea’s traditional ally and friendly countries - including the George W. Bush administration in the US, as well as Great Britain, France, Canada, and Australia - spearheaded sanctions on Seoul. Then-US Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security John Bolton insisted that the incident was a serious violation of the IAEA Safeguards Agreement that should be referred to the UNSC. It took all the diplomatic capabilities of the National Security Council (NSC) standing committee before the IAEA eventually concluded its safeguard consideration by saying it “welcomed the corrective actions taken by the Republic of Korea, and the active cooperation it has provided to the Agency.”

As part of the process, then-NSC deputy secretary-general Lee Jong-seok had to pay a visit to Bolton in the US, while the Ministers of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Unification, and Science and Technology pled South Korea‘s “innocence” with presentations on their “four principles on the peaceful use of atomic energy.” Many suggested the stern response from Washington and others could have been the result of the Park Chung-hee administration’s prior record of attempted nuclear development in the late 1970s.

“If we’re going to advocate nuclear armament for the purposes of autonomy and defense, we first need to regain the wartime operation control we handed over the US,” said Choi Jong-gun, a professor of political science and international studies at Yonsei University.

“These calls for nuclear armament aren’t just something the US opposes, but also ridiculous in terms of pressuring China,” Choi argued.

A former senior government official warned of the consequences if South Korea does call for the redeployment of US tactical nuclear weapons after agreeing to discuss the deployment of THAAD.

“Apart from any question of whether it‘s realistic, China is going to take it as South Korea declaring itself an agent of the US,” the former official said.

By Lee Je-hun, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’ [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/5217153290112576.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’![[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/7717153284590168.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change- [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

Most viewed articles

- 1Behind bellicose bluster, N. Korea is turning airfields into greenhouse farms

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

- 4Yoon rejects calls for special counsel probes into Marine’s death, first lady in long-awaited presse

- 5[Column] “Hoesik” as ritual of hierarchical obedience

- 6How S. Korea’s Yoon flushed 30 years of ties with Russia down the drain

- 7Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 8‘Free Palestine!’: Anti-war protest wave comes to Korean campuses

- 9[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

- 10Yoon voices ‘trust’ in Japanese counterpart, says alliance with US won’t change