hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] The unsolved problem of S. Korea’s hidden landmines outside front lines

Rainwater beaded on the thickly clustered trees. Occasionally, people would wander along the walking trail that led among them. “If it weren’t raining, there would have been a lot of people out here walking or jogging,” one of the strolling residents said. Farther down the narrow trail was a sign reading “PAST MINE ZONE.”

An information board behind the sign bears the following message: “No admission is allowed to this area, which is a former minefield. Since unrecovered or displaced mines carry a risk of accidents, please stick to the marked trail to ensure safety on your hike.”

On Oct. 2, raindrops were falling on Mt. Umyeon, in Seoul’s Seocho District, as Typhoon Mitag, the 18th storm of the season, raged nearby.

The demilitarized zone (DMZ), which separates the South and North Korean front lines, is not the only place where mines were laid. There used to be minefields a short distance from popular hiking trails. One good example is the air defense base operated by the South Korean Air Force at the summit of Mt. Umyeon.

From 1953, when the armistice agreement was signed, until the 1980s, the South Korean military buried antipersonnel landmines around air defense bases and ammunition depots far from the front lines. These mines were supposed to defend these military facilities. In the 1980s, the military buried a thousand M14 antipersonnel mines (known as “toe poppers,” since they’re designed to maim the foot/ankle, not kill) around these air defense bases. After landmines lost utility in facility defense, the military removed 982 mines from Mt. Umyeon between 1999 and 2006, but it couldn’t find 18 of them, which were presumably displaced.

Despite concerns that displaced mines could cause injury, Koreans continue to go on hikes and use exercise equipment located right next to the old minefields. There isn’t even barbed-wire fencing or visible warning signs at some of these sites, making it possible for civilians to stumble right into one of the old minefields. But safety management isn’t the responsibility of local governments.

“The hiking trails formed naturally, and the district government only handles basic maintenance of the trails. The military is supposed to be in charge of landmine safety,” said an official at Seocho District Office. According to the official, the military needs to be more proactive about this issue.

Mt. Umyeon is one of 40 minefields in the rear area dotted around the country. Statistics about mine removal around rear air defense bases provided by the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to Min Hong-cheol, a Democratic Party lawmaker on the National Assembly’s National Defense Committee, show that a total of 53,700 mines were laid in the rear (not including the mines in the DMZ). 50,679 of those mines were removed, but that leaves 3,021 still in the ground. These missing mines are buried at 37 sites around the country like Mt. Umyeon, including Haeundae, Busan; Seongju, North Gyeongsang Province; Gimhae, South Gyeongsang Province; Ulsan; and Seongnam, Gyeonggi Province. Mines have been completely cleared from just three of the 40 sites, namely Gachang, Daegu; Incheon; and Mt. Geumo, Gumi.

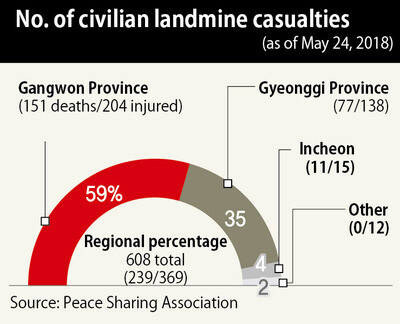

The problem is that the unrecovered mines are liable to injure unlucky passersby. According to records collected by the Peace Sharing Association (the Korean Campaign to Ban Landmines), a NGO that provides assistance to victims of landmines, there have been a total of 608 such victims from the end of the Korean War through May 2018, with 239 killed and 369 injured.

“Since it’s nearly impossible to collect statistics for those who have already been killed by landmines or who moved to another area after the accident, the actual number of victims could be much higher,” said a source from this organization.

Hidden landmines source of injury for civilians and rescue personnel

Concerns about potential victims have been magnified by the fact that these rear minefields are in areas that are easy for civilians to access while hiking or driving. Mines that have shifted in landslides, heavy rains, strong winds, and earthquakes could easily end up on hiking trails. In one tragic accident in 1984, 60 people were killed or injured when a displaced mine detonated on Mt. Jangneung in Gimpo, Gyeonggi Province. Landmines can be a deadly problem not only in landslides but also in forest fires. During a fire on Mt. Gogeum, in Pohang, North Gyeongsang Province, in 2009, an old minefield blocked the path of firefighters, making it harder for them to put out the blaze. And during a forest fire on Mt. Jungni in Busan’s Taejongdae Park in 1987, firefighters on the job were injured when they stepped on a mine.

Finding the 3,021 mines that remain unrecovered around the country is no easy task. The M14 antipersonnel mines that were buried in the rear-area minefields are small and light — measuring 5.5cm wide and 4cm high and weighing just 112g — which makes them more likely than other mines to float downstream or be blown around by the wind. Even worse, there are several areas where troops didn’t keep accurate records of where they’d buried mines.

The South Korean military has been working on clearing mines in the DMZ and the rear since the 1990s. An average of 440 million won (US$368,418) is spent each year, resulting in the removal of around 500 mines. It’s estimated that 1.27 million landmines are buried in South Korean territory alone (520,000 in the DMZ, 740,000 north of the Civilian Control Line, and 10,000 south of that line); at this rate, environmental group Green Korea predicts, it will take more than four centuries to remove all the mines in the country.

Detecting and removing mines is unavoidably a time-consuming process. Haste is out of the question, given their explosive nature, and it’s necessary to make a painstaking sweep through huge areas that are likely to hold some landmines. When the mines don’t show up on a mine detector, the only way to clear them is to remove all the trees from the suspected minefield and then dig up each square of earth.

Taiwan cleared all mines on Kinmen Island in just 7 years

For such reasons, Taiwan is being hailed as a worthy example. In 2006, Taiwan adopted the International Mine Action Standards. Working with civilian experts, the government was able to clear all the mines on Kinmen Island, which were laid during the conflict between the Communists and the Nationalists, in just seven years. After the passage of the Landmine Prevention Act, the military command devised the plans, while the defense command took charge of the organizational aspects. The mines were cleared through a partnership between the private sector and a military mine removal team. The project cost US$84 million, and not a single person was injured.

“The issue of neglected mines isn’t something we should just leave to the Ministry of National Defense. The government needs to be proactive about serving as a ‘control tower’ for mine removal and working with NGOs with the technical knowledge to quickly clear landmines in the rear and south of the Civilian Control Line,” Green Korea said.

“At this very moment, we’re working briskly to remove landmines. In the rear, we clear mines after ensuring the safety of civilians by putting up barbed-wire fences and warning signs. Allowing the participation of the private sector is worth considering, but the law currently prevents civilians from engaging in mine removal,” said an official with the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

By Chai Yoon-tae, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’ [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/5217153290112576.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’![[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/7717153284590168.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change- [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

Most viewed articles

- 1[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

- 2[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

- 3Yoon rejects calls for special counsel probes into Marine’s death, first lady in long-awaited presse

- 4Korea likely to shave off 1 trillion won from Indonesia’s KF-21 contribution price tag

- 5[Book review] Who said Asians can’t make some good trouble?

- 6Nuclear South Korea? The hidden implication of hints at US troop withdrawal

- 7[Column] “Hoesik” as ritual of hierarchical obedience

- 8Young Koreans vent rage over working hours already all too grueling

- 9When and why did Koreans go from anti-American to pro-US?

- 10Birth of Jesus in Korea