hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] The dark underbelly of K-pop audition programs

Broadcasters’ arts and entertainment bureaus are constantly thronged by visitors. As though traveling on a pilgrimage, entertainment agency managers come to “say hello” to the producers there. A few months ahead of some new release, managers start wearing down the carpets at the three terrestrial and various cable networks, attempting to make a strong impression. It’s a practice called “facetiming,” where the managers are doing business in person with the producers.

With 60 to 70 names on the facetiming wait list for the average day, entertainment agency employees wait for the chance to have a brief meeting of less than five minutes with a producer. The encounters -- opportunities for the companies to busily pitch their products, provided they aren’t disrupting the producers’ normal duties -- have a big impact on which artists with new releases end up appearing on music and entertainment programs. It’s heartening to hear that “diligence” is such a gauge of opportunity, but it’s also chilling to consider that the task of weighing that diligence lies in the hands of just a few producers. That’s all the more true when shadowy relationships outside the company come to factor in those diligence assessments.

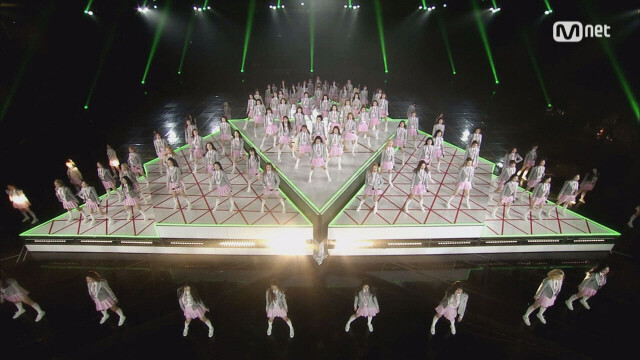

While it has diminished somewhat since the Kim Young-ran law went into effect, it remains an open practice for entertainment agencies to wine and dine the arts and entertainment divisions. It’s the reason industry observers were hardly surprised by reports of evidence that producers with the Mnet hit audition program “Produce X 101” received this kind of agency treatment. Outside the Seoul area, it’s still common practice for agency officials to pay for a group celebration after a music show; as recently as a few years ago, aspiring “idols” were summoned to attend evening gatherings between networks and agency employees.

It all seems like something out of the past: the image of pop ground members lining up and waiting to offer deep 90-degree bows to the producers after a music show has been completed. When you consider the “postmodern” aspects of the K-Pop wave, the premodern practices on the other side of that seem quite incredible. The reason this kind of cultural stagnation takes place on the cutting edge of culture is because South Korea’s music and entertaining broadcasters -- even after the emergence of direct communication channels through formats like YouTube -- still hold a dominant influence.

According to management industry insiders, CJ ENM has taken this kind of broadcaster influence structure to the next level, extending its reach beyond broadcasting, music distribution, and production into management with its “Produce” series. CJ ENM has seized control of the sales framework for “idol products,” producing and distributing music through its affiliates and taking on a management role by having artists appear on music and entertainment programs. This explains why KBS and JTBC copied the “Produce” model wholesale to create their own idol audition programs, although they ended up flopping.

For smaller entertainment agencies that need access to the broadcasting train to find their way into the global market, there is no way to avoid “the call” when a broadcaster comes up with an audition program based on the Produce series format. It’s a chance to debut an artist or two at a relatively low cost; for the small companies, it’s worth the cost of a little wining and dining. Production costs reportedly run in the neighborhood of 300 to 500 million won (US$258,285-430,474) for even an EP release by an idol group.

Since the start of season one of “Produce,” the program’s market stranglehold has only grown. Only a very few idol groups have managed to succeed with independent debuts at one of the smaller entertainment agencies outside the “big three.” Only groups like IOI or Wanna One that made their debut through “Produce” or count “Produce” performers among their members have been able to grab the public’s attention. They make sure to appear on the “Produce” series, if only to avoid their “big break” turning into a big bust. On the surface, the opportunities on these programs would seem to be distributed evenly among the small agencies rather than the big three; in fact, the framework has if anything laid waste to “local businesses” among teen pop acts.

All of these unfortunate efforts happening with the pillars of the K-Pop industry, from the YG episode to the situation with Mnet’s “Produce,” could be the result of an effort at leveraging the practices of an old era to break through the new one. In the meantime, young managers continue pounding the pavement with the broadcasters, nursing “BTS dreams,” while countless aspiring young artists toil away relentlessly in the rehearsal studios.

By Um Ji-won, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Caption: The logo for Mnet’s audition program “Produce X 101”

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0514/2317156736305813.jpg) [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

[Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line![[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0514/7917156741888668.jpg) [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

- [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

- [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

- [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- 2Major personnel shuffle reassigns prosecutors leading investigations into Korea’s first lady

- 3[Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- 4[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- 5US has always pulled troops from Korea unilaterally — is Yoon prepared for it to happen again?

- 6Exchange rate, oil prices, inflation: Can Korea overcome an economic triple whammy?

- 7[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- 8[Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

- 9Korean opposition decries Line affair as price of Yoon’s ‘degrading’ diplomacy toward Japan

- 10Naver’s union calls for action from government over possible Japanese buyout of Line