hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Special report] Fixing government policy for young people

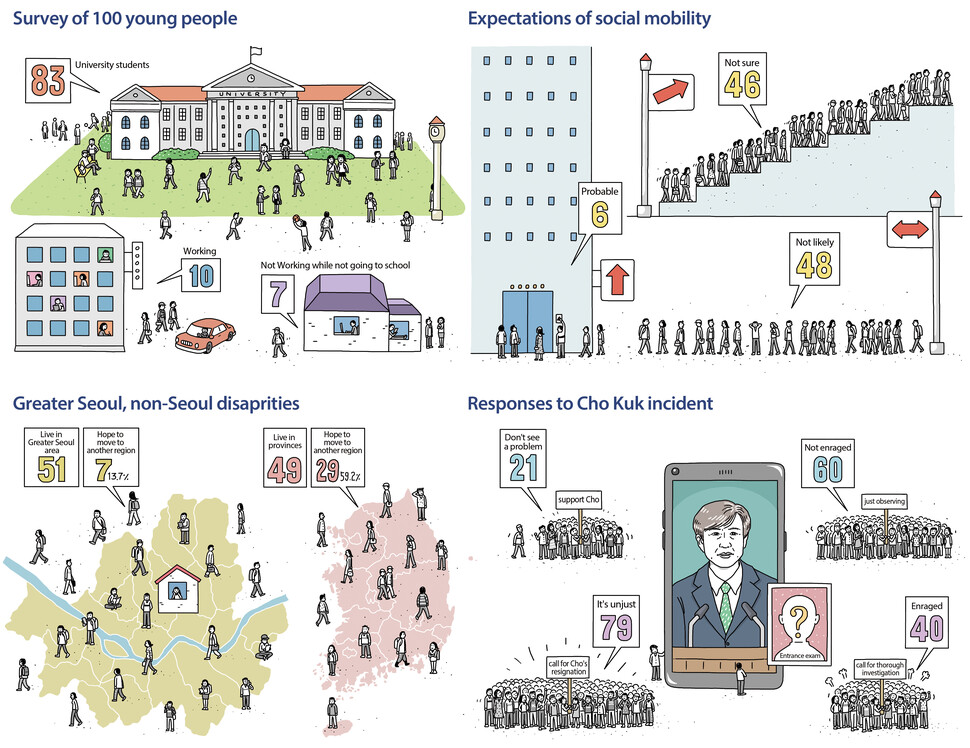

As the Hankyoreh met with young South Koreans, what it focused on most was “differentiation.” Experts agreed that the national government should likewise focus on specialization among young people in its approach to youth policy.

To begin with, some are suggesting that that youth policy should be viewed as a matter of designing a new society for the future rather than job, welfare, or population policy. Kim Ji-kyung, a senior research fellow at the National Youth Policy Institute (NPYI), explained, “Young people are differentiated vertically according to class, and also horizontally according to their current occupational status -- such as whether they are enrolled in university or seeking employment -- and the values they pursue.”

“Policies need to be pursued in a way that takes this differentiation into account,” Kim stressed.

In particular, Kim noted the importance of listening to “groups of young people who have been left out.”

“There’s been a lot of talk recently about the fairness issue for young people, and nobody is paying attention to the young people who aren’t enrolled in college and don’t even have access to the ‘fair competition’ track. That imbalance needs to be mitigated,” Kim said.

Indeed, young people are viewing various issues differently from the past. Discussions of a “safety net” are frequently seen as focusing on income in economic terms -- but young South Koreans look beyond mere income for things such as an environment where they can work securely without suffering “bullying” by their workplace superior.

“Policies need to be focused on establishing a ‘livelihood safety net’ where people can feel secure while engaging in ordinary economic and social activity,” Kim said.

Choi Seong-soo, a Yonsei University sociology professor who studies the effects of university background on students’ social mobility, said more attention should be given to junior colleges, where voices are rarely heard.

“In our research, we found a matter where students from junior colleges earned a relatively high income at their first job. It was the only group where early labor market performance has been gradually improving, as opposed to other university categories,” Choi said.

“A lot of students go straight to junior colleges after graduating high school, but others work for a time before returning to junior college,” he noted. “With their focus on education for specific professions, junior colleges are basically playing the role of institutions where you can receive an education while you’re looking for an alternative in life.”

But South Korean society tends to categorize junior colleges as an area of “failure” within a hierarchical system.

“We need to get rid of this habit of focusing just on upward mobility,” Choi argued. “All the four-year university students in Seoul are focusing on the decrease in opportunity to get full-time or specialized jobs at large corporations, but this is skewed representation for a portion of young people.”

“That’s the kind of situation you see in the current ‘fairness’ debate,” he said.

“Strengthening junior colleges is a way of supporting the employment of young people and helping them achieve economic stability, but society just doesn’t pay much attention,” he noted.

Addressing lack of jobs in provincesSome suggested the provincial university issue should be considered together with city- and job-related issues. Yang Seung-hoon, a sociology professor at Kyungnam University, said, “In South Korea at the moment, it doesn’t look like there are any regions capable of providing jobs other than the Seoul area and the Busan/Ulsan/South Gyeongsang area. But even in the Busan/Ulsan/South Gyeongsang area, jobs are disappearing as technology advances and we enter a ‘post-skilled labor’ era.”

In the past, a person hoping to work at Hyundai Motor in Ulsan had to undergo six months of education at a job training society. Today, process standardization and automation have reportedly made it possible for workers to assemble on their own after just a day or two of training. The result has been lower demand for work, along with a decline in wages and benefits for workers.

“We need regional planning that takes advantage of regional characteristics to attract investment and broadening the regional economic zone itself to achieve shared growth,” Yang said. “Urban policy and youth policy should be pursued together.”

“In the heavy industry cities, what high-quality jobs exist are male-centered,” he noted. “The government needs to recommend proactive implementation of female worker quota systems not just for public enterprises but also private ones.”

By Jung Hwan-bong, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 3Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 4[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 5Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 6S. Korea “monitoring developments” after report of secret Chinese police station in Seoul

- 7Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 8Inside the law for a special counsel probe over a Korean Marine’s death

- 9USFK sprayed defoliant from 1955 to 1995, new testimony suggests

- 101 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows