hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Reportage] Abandoned by their families, young parents turn to illegal loaning businesses

Lee Seung-eun (pseudonym), now 21, awoke to a pain running through her lower back. Although the sign said it was a “24-hour café,” she could not help feeling self-conscious about the employees watching. Her husband Kim Ji-hoon (pseudonym), now 20, looked at her with pain in his eyes. As she spent a sleepless night on a café chair on the outskirts of Seoul in March 2019 -- the fourth month of her pregnancy -- Seung-eun suddenly felt sadness welling up within her. The nausea had stopped, but her body was swollen and her back had been aching. After opening her eyes, she once again slumped over the café table. She’d been eating hamburgers all month, but she didn’t know if she could stomach it that day. “How long do I have to put up with this?” she wondered.

She wanted to go to a bathhouse or a motel where she could lie down comfortably. But the two teenage parents’ pockets were empty after they’d been left to wander the streets amid their families’ objections to having the baby. Even the electronic payment systems on their mobile phones had been cut off. Never mind pursuing any kind of prenatal education for the baby in her belly -- since leaving home, Seung-eun had had to spend every morning worrying whether she would get something to eat that day. More than anything, she felt weighed down by the constant threats from debt collectors. She’d borrowed 100,000 won (US$86.27) from an acquaintance, which had since ballooned with interest.

The intimidating collection tactics -- the kind of thing she had seen on the news -- were enough to leave the pregnant Seung-eun terrorized. Teenage parents like her have had to experience the very depths of hopelessness simply because of their decision to bring a new life into a world where they have no family, country, or friends reaching out a helping hand to them.

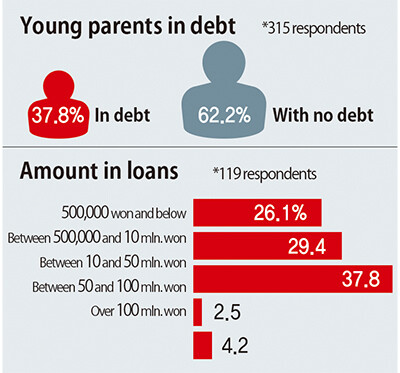

Ji-hoon and Seung-eun are not the only such couple. Surveys show that many young parents who have been abandoned by their families and face social isolation have turned to illegal loan businesses and individual lenders. On Jan. 12, the Hankyoreh acquired an exclusive copy of a research report on young parents published by the Beautiful Foundation and the Korean Unwed Mothers Support Network based on interviews and questionnaires administered to 315 parents aged 24 and under. It is essentially the first report on conditions facing young South Korean parents.

1 in 3 young couples living with debt

According to the findings, one out of three young parents who had a child in their teens or early 20s is living with debt related to child-raising costs. Currently, the only system available to support young people with children is the Single-Parent Family Support Act, which provides for support to single-parent families. This is why many young parents have been forced to the edge with nowhere to turn. With mothers 19 and under accounting for 1,300 of the 326,822 infants born in South Korea in 2018 -- and mothers 24 and under according for 14,600 -- many are arguing that the state should take action to support young parents.

Ji-hoon was a student in his second year of high school when the baby was born. Seung-eun had already left school, having taken an equivalency exam in her first year of high school. It was also Ji-hoon who had taken the initiative in convincing Seung-eun to have and raise the child. “I thought, ‘Now that there’s a child, we have to do whatever it takes to raise it,’” the teenage father told the Hankyoreh on Jan. 8, his expression seemingly serene.

But their families’ response to the new life was chilly. In February of last year, Ji-hoon and Seung-eun confessed to their families that she was pregnant. Both of their families adamantly insisted that she have a “procedure.” Seung-eun’s own mother had had her at the age of 21, and her grandparents were worried about their granddaughter following the same path. Unable to agree to their families’ decision, Seung-eun and Ji-hoon left home. They went to stay at a friend’s home, working part-time in restaurant serving jobs. There seemed to be hope that the two could survive while caring for a child.

That hope evaporated after two weeks when Ji-hoon family members showed up at their place of employment. His mother and aunt summoned Seung-eun to an OB/GYN clinic and presented her with a document. “Abortion consent form,” it read. Belatedly learning of this, Ji-hoon rushed over and whisked Seung-eun away from the clinic. Thus began the “days of despair” for the young couple.

No one reaches outThe friend who helped the teenage couple had since moved away, and Ji-hoon and Seung-eun were literally out on the street. They used the electronic payment systems on their mobile phones to rent motel rooms or stay in bathhouses.

The motel manager at least was lenient about checkout times, worried for the young parents-to-be. But the bathhouse had restricted hours for minors, and the two were forced back on the street by 10 pm. At that point, they would head to the 24-hour café to spend the rest of the night. Expecting mothers require adequate nutrition, but Seung-eun subsisted on hamburgers for a full month. “I was craving meat,” she said. “But it’s so expensive. The kinds of foods I could eat were limited.”

As time went on, they reached the monthly limit of the mobile phone payment system, which was in the range of 300,000-500,000 won (US$258.79-431.31). They borrowed 100,000 won from a private loan business on social media. The loaner demanded that they provide a written promise to repay 300,000 won –- 200,000 won (US$172.51) in interest -- within the month. They hadn’t been concerned at the time, with their part-time work paychecks coming to them shortly. They were in such need of money that they went ahead and signed the promise. As soon as their paychecks arrived, they paid back the principal.

Then the hounding began, with the acquaintance going after them for not paying the interest. The loaner put a public message on Facebook with their real names and a photograph of Seung-eun’s first child, accusing them of “not paying back their debts.” “I’ll kill them,” the loaner wrote. The comments were filled with insulting and sexual comments about the two of them. One person falsely claimed that they had “gone for an abortion” and suggested “reporting them.” With the unpaid mobile phone payments and the borrowed money, their debts swelled to 1.5 million won (US$1,294).

“It was really bad. If you asked me to rate [the severity] on a scale from one to 10, it was a 10. But we were so exhausted we didn’t report it,” Ji-hoon said. His face was grim, as if the hellish experience of that time were on his mind.

Perhaps as a result of the hounding and the unstable housing situation, Seung-eun was hospitalized five to six times before the baby was born. At one point, she was taken to the emergency room with heavy blood discharge. It was a symptom of abruptio placentae, in which the placenta separates from the uterus. At the hospital, she was told that this was a result of stress. The two were again left to wander in their despair.

Many young parents lacking economic means have similar experiences to those of Seung-eun and Ji-hoon. According to the results of the young parents survey, 37.8% of young parents, or 119 out of 315 -- with an average age of 18.7 at the time of pregnancy -- reported having debts. Among the 315 parents surveyed, 45 (37.8%) cited debts between 10 million and 50 million won (US$8,624-43,113); 35 (29.4%) cited debts between followed 5 and 10 million won (US$4,313-8,627). Five of the respondents (4.2%) reported having debts of “100 million won [US$86,267] or more.”

The reason young parents borrow money generally have to do with child-raising and housing costs. Fully 77.2% of respondents reported taking out loans for housing, child care, and living expenses (multiple responses allowed), followed by communication costs (15.2%) and school expenses (6.1%). More than half of the young parent respondents -- 57.6% -- had borrowed money from a bank, but a number had also taken out illegal loans. The 17.6% who reported using the services of loan sharks and social networking service (SNS) private loans outnumbered the 15.2% who reported borrowing from family members and friends.

A miraculous helping hand from societyFortunately for Seung-eun and Ji-hoon, someone was there to reach out a miraculous helping hand. Through a vocal teacher of Seung-eun’s, they learned about the Korean Unwed Mothers Support Network (KUMSN), and they were soon put in touch with the Kingmaker, a group providing assistance to young households unable to support themselves. At the time, Seung-eun was entering her fifth month of pregnancy. The couple was allowed to stay at the “119 Emergency House” operated by Kingmaker in Incheon. Even though it was a cramped space attached to the facility, it could not have been more precious to the two of them. Ji-hoon was able to return to school, which he had been unable to attend. He would take the first train from Incheon to Gwangju, Gyeonggi Province, at 5 am to go to classes; later on, he transferred to a different school and studied baking and carpentry.

Kingmaker’s “119 Emergency House” was a safeguard for these young people after their own family members and society forsook them. When Ji-hoon’s school moved to take disciplinary action against him for fathering a child at his age, Kingmaker averted the threat by noting that no such regulation existed in the school rules. It also provided financial education to the couple, including teaching them how to keep a household ledger. Most importantly, the group raised funds from small contributors and found the couple a two-room rental apartment, providing them with a deposit and 500,000 won (US$431.36) to cover their rent. After gaining this small fence of their own, Seung-eun and her husband agreed that residential assistance was crucial to young parents like themselves.

“Without a place to live, we couldn’t work or go to school. But even when I was thinking, ‘Why do I have to live this way? Should I just give up?’ I would always change my mind.”

Having found a bit of stability, Seung-eun gave birth to their child in August of last year. Ji-hoon’s hand trembled as he cut the wailing newborn’s cord.

“My hands were so sweaty that I couldn’t put on the rubber gloves right. The baby was so cute, and so small I was afraid it might break.”

Seung-eun and Ji-hoon have now become full-fledged parents -- but the government assistance available to them remains inadequate. Seung-eun receives 200,000 won (US$172.56) a week in single parent support for her first child, but since she started weaning her daughter, her monthly food expenses alone amount to between 500,000 and 600,000 won (US$517.51). Neither child has yet received inoculations, which cost money. Even the single parent assistance could end up being cut off.

The neighborhood center informed her that she “can’t continue receiving single parent benefits in a common-law marriage,” although she was told they would look into basic livelihood security benefits.

Still considered a minor and with his parents not granting consent, Ji-hoon has yet to register his marriage to Seung-eun. For the young couple to acquire Korea Land and Housing Corporation (LH) key money deposit rental housing or young persons’ rental housing, they would have to either be legally recognized as a married couple or come up with the money for a deposit. Even benefits through the basic livelihood security system would require the content of Ji-hoon’s parents, who are considered legally obligated to support him. Without single parent assistance, no avenue yet exists in South Korean society for young parents like them to receive support.

“Without the option of bank loans, underage parents in their teens are forced to turn to illegal loans and high-interest lenders,” explained Bae Bo-eun, president of Kingmaker, which provides assistance to young families unable to support themselves.

“There’s a vicious cycle that arises as these financial problems are repeated and the couples’ relationship falls apart, resulting in the child being neglected or abused,” Bae said.

In the past few days alone, Seung-eun has been facing a battle, having to take their child to the hospital with the flu. But for these two young parents, the child represents their only hope.

“I call my baby ‘Sun.’ We originally called it ‘Moon’ because it was so round, but the moon is dark. I want it to shine bright like the sun,” Seung-eun said, cradling her five-month old second child tightly in her arms.

By Bae Ji-hyun and Kang Jae-gu, staff reporters

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 3N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 4Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report

- 5[Reportage] On US campuses, student risk arrest as they call for divestment from Israel

- 6Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February

- 7[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 8‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 9[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 10[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol