hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

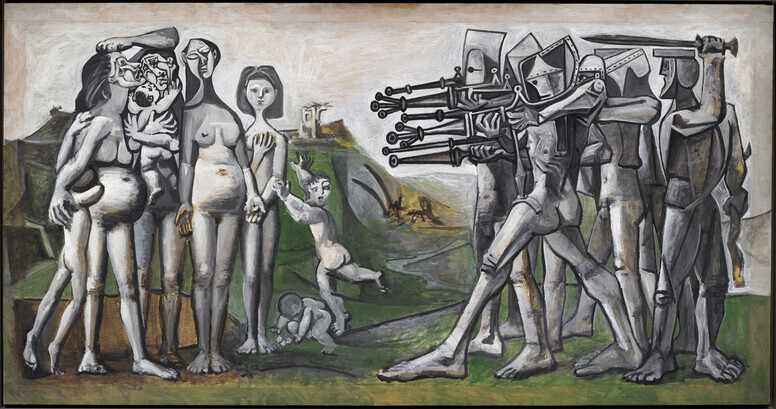

Picasso’s “Massacre in Korea” comes to Korea for first time

“I can’t believe it. I never expected to see this painting in Korea,” said Chung Young-mok, an emeritus professor at Seoul National University who is considered one of the Korean art history world’s foremost authorities on the painter Pablo Picasso (1881–1973).

Chung was speaking about “Massacre in Korea,” a 1951 work by Picasso that remains a lightning rod for controversy even today, with conservative and progressive scholars and artists in Korea debating its “ideology.”

The work is also the centerpiece of the “Pablo Picasso Retrospective” that has been taking since early May at the Seoul Arts Center’s Hangaram Art Museum in Seoul’s Seocho neighborhood.

Set against the scorched field of a battleground, “Massacre in Korea” presents a stark contrast between the naked women and children on its left and the armed young men pointing guns on its right.

The work led to Picasso being tarred as a “red.” Since the artist had joined the Communist Party in 1944, many in the US and elsewhere alleged that the work was intended as propaganda against the US military.

The situation obviously was no different in South Korea, an anti-communist country subject to US influence. Since it was first shown in May 1951, the idea of it being shown in South Korea had remained more or less unthinkable — although the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea had made efforts to show it since the 2000s.

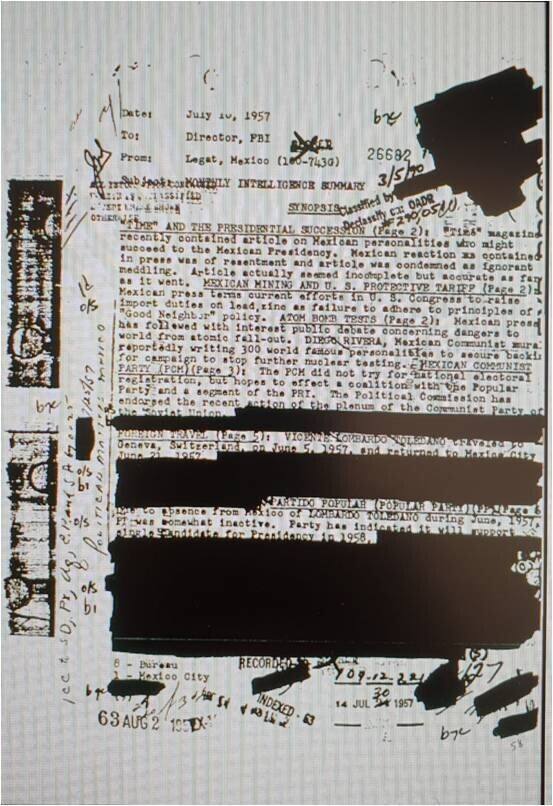

As recently as the early 1970s, the mere mention of Picasso’s name was taboo in South Korea. He was subject to intensive surveillance by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation because of his artwork, and as a result his name was removed from a brand of oil pastels, while an image of “Massacre” was blacked out in copies of the book “Collection of World Art” imported from Japan.

In the 1990s, images of the painting began slipping into art journals, and by the 2000s it was circulating online. Even so, the mood remained cautious.

Even when the agency behind the latest exhibition made its decision to show the work, others continued arguing against it, suggesting that it risked serious consequences by rushing to show it.

Opinions on the painting have tended to be sharply polarized. Progressives have lauded it for expressing an antiwar message with its depiction of the horrors of war, although some have also complained that the painter did not explicitly identify who the perpetrators and victims were.

Among conservatives, the predominant view has been that the painting represents “propaganda,” highlighting only the atrocities committed by US forces while ignoring those committed by the North Korean communists who started the war in the first place.

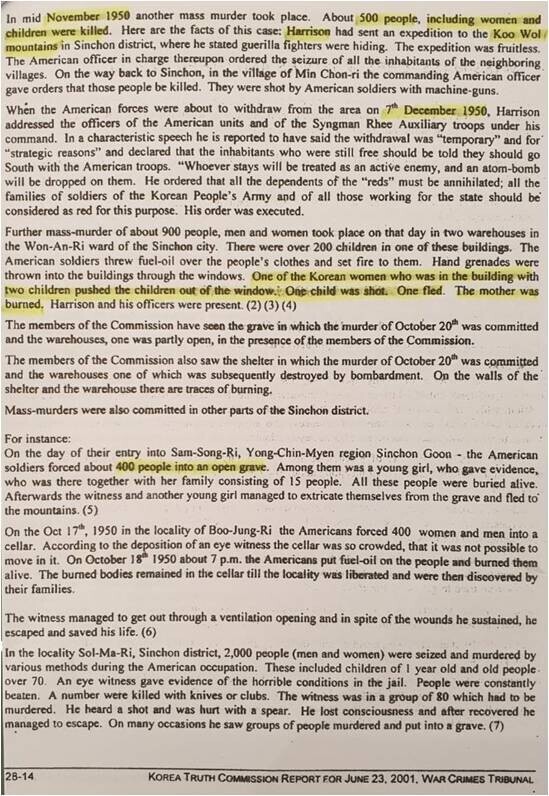

An example of this was seen in a column by a history professor published in a conservative daily early this month. In it, the writer blasted Picasso for making a propaganda painting based on false reports that US soldiers had committed the Sinchon Massacre in Hwanghae Province.

How has the image come to attract so much ideological debate? The controversy has been fanned by questionably founded claims that Picasso was inspired to paint it by the Sinchon Massacre, allegedly committed by the US military.

Most results from a search for the painting on portal sites such as Naver include explanations that it was based on the Sinchon Massacre. But a closer look shows the basis for this claim is anything but clear.

Chung Young-mok, who has researched the topic, offered quite a different story in the historical facts he shared during a special “Massacre in Korea” roundtable held on June 25 in front of the artwork at the Seoul Arts Center gallery.

According to Chung, a 1952 report on the findings of an on-site investigation in North Korea by the International Association of Democratic Lawyers (IADL) states that the first victims of the Sinchon Massacre were killed on Oct. 18, 1950, with another 35,000 people slain over the next two months through December.

It was on the basis of these findings that North Korea used the town to build its Sinchon Museum of American War Atrocities in 1958.

According to scholars, Picasso began working on the painting around September 1950. It took four months to complete.

But the first internal North Korean reports on the massacre date to October 1950, and it was not until the IADL published its report in June 1952 that the rest of the international community learned about it. On this basis, Chung is firmly convinced that the painting bore no connection with the Sinchon Massacre.

Being based in France and having never visited North Korea himself, Picasso would not have been able to know ahead of time about the Sinchon Massacre in September 1950.

As we look upon this masterwork making its first appearance in South Korea 70 years later in June 2021, we sense that the time has finally come to clear up the misunderstandings.

By Noh Hyung-seok, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0509/221715238827911.jpg) [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

Most viewed articles

- 1Korea likely to shave off 1 trillion won from Indonesia’s KF-21 contribution price tag

- 2Nuclear South Korea? The hidden implication of hints at US troop withdrawal

- 3[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- 4With Naver’s inside director at Line gone, buyout negotiations appear to be well underway

- 5In Yoon’s Korea, a government ‘of, by and for prosecutors,’ says civic group

- 6[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 7‘Free Palestine!’: Anti-war protest wave comes to Korean campuses

- 8How many more children like Hind Rajab must die by Israel’s hand?

- 9Overseeing ‘super-large’ rocket drill, Kim Jong-un calls for bolstered war deterrence

- 10[Photo] ‘End the genocide in Gaza’: Students in Korea join global anti-war protest wave