hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Seoul travels] Waiting for the bell to toll in Jongno, walking in the steps of Admiral Yi Sun-sin

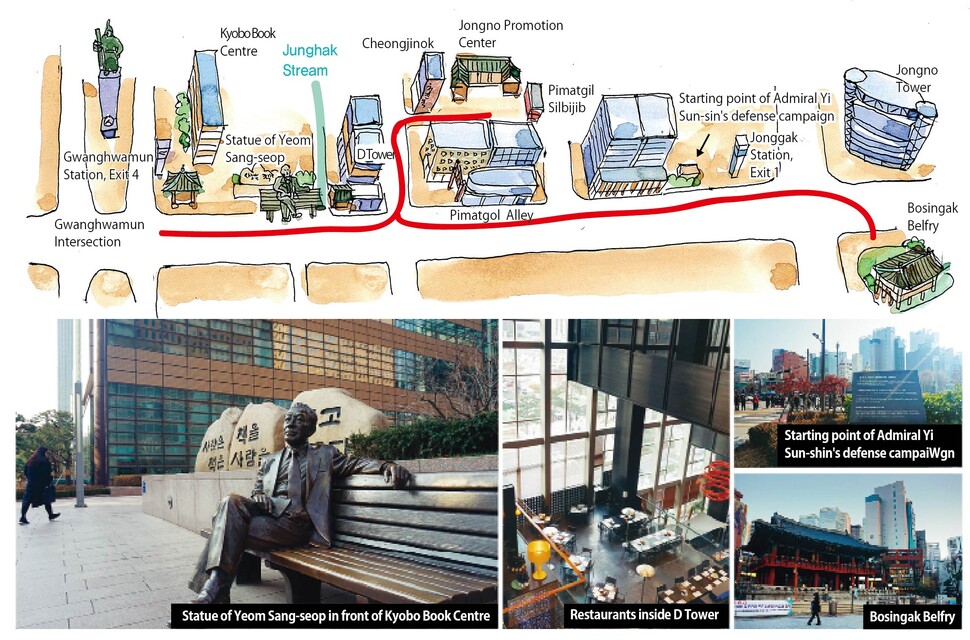

The area around Jongno Intersection in Seoul used to be known by the name “Unjongga.” The name meant an economic hub area where people and items “congregated like clouds.” But in contrast with this historic reputation, the Jongno streets that greet me as I head out of Exit 4 of Gwanghwamun Station are startlingly quiet — a reflection of the COVID-19 pandemic that has dragged out into the long term. The slogan once declared, “Together, we live; separate, we die.” Today, we seem to have adopted a new survival strategy that says, “Together, we die; separate, we live.”

A similarly forlorn atmosphere surrounds the statue of novelist Yeom Sang-seop on a bench in front of Kyobo Book Centre. This is normally a popular meeting spot, but today there’s hardly anyone around. Yeom was born in the Jongno area in 1893, and his birth home is said to be nearby, making him a Jongno native through and through. He’s famous for having started a new literary movement with books such as “Tree Frog in the Specimen Room.” His pen name “Hoengbo” literally means someone who “walks sideways” rather than straight ahead. The world today seems to be following his lead, lurching precariously to the side.

Next to the statue is the excavation site of the Joseon-era commercial district known as “Sijeon Haengrang.” This was a government-run market street where businesses received official permits and paid taxes. At one time, it was home to over 1,400 stores selling everything from rice, mixed grains, and other foodstuffs to silk and other fabrics, firewood, and various daily essentials. It is said to have operated under a principle where one store was only allowed to sell one type of item. Junghak Stream, said to be the largest of the Cheonggye Stream tributaries, has been restored as an artificial waterway along the road next to Kyobo Book Centre.

Recent changes to the road between Kyobo and Jonggak Belfry have rendered it almost unrecognizable. The old buildings have been torn down and replaced with modern structures like D Tower and Soho. D Tower is a high rise with offices on the upper floors and restaurants and cafes on the lower ones. Its appealing interior and fresh sensibility have lured in many young working professionals. This is not an old-fashioned market district with traditional restaurants, but a battleground where modern establishments compete. It’s worth visiting just to ride the escalators and look around.

From there, it’s on to Pimatgol Alley. Because of its proximity to government offices, Jongno was often visited by people of high station traveling on horseback or in palanquins. For commoners, this meant the hassle of frequently having to prostrate themselves in kowtows. The name Pimatgol (alternatively Pimatgil) comes from the word pima, meaning “to avoid horses,” as people here would use the narrow alleys behind Jongno Road to avoid stumbling upon high-ranking visitors. This area has also long been associated with artists and writers. In a piece for the “Monthly Samtoh,” novelist Choi In-ho said the alley was his “emergency exit” before he became famous.

“Intoxicated by the powerful scent of fish being grilled on a brazier placed outside in the alley, I had no choice but to go inside the restaurant and eat lunch alone. The humble joint was packed with office workers who had come from nearby buildings to have lunch,” Choi wrote.

And sure enough, Pimatgol Alley now only exists in our memories.

Initially, the alley was the default lunch destination for office workers in the Jongno area. The capable cooks in the area filled hungry bellies at lunch time and satisfied emotional needs in the evening by selling booze and snacks at reasonable prices.

But the neighborhood gradually declined, and economic logic brought in newfangled buildings. Today, all that remains of Pimatgol is the name. The alley’s traditional eateries have been replaced by D Tower, Le Meilleur Jongno Town, Cheongjin Shopping Street, and Sikgaekchon at Gran Seoul.

Old alleyways are like old mothers — a precious part of our lives that we must not abandon. The total elimination of that storied dining area is something that I’ll long view with sadness.

One of the old restaurants is still in business, though: Cheongjinok, on Jongno 3-gil, one of the side streets running toward Jongno District Office.

Since opening in 1937, Cheongjinok has been a favorite with government officials, office workers, and journalists in the Gwanghwamun area. It is also a place where wiped-out salarymen go to recover from a company drinking session the previous evening. Some younger people are turned off by the pungent aroma of the haejangguk (hangover soup) served there, but the restaurant has managed to keep its lights on.

There’s something about a restaurant’s location that affects the quality of its food. That’s a lesson we can learn from Hadonggwan, a restaurant renowned for its gomtang (beef bone soup). Regulars at the restaurant complain that, after it moved from its old location in the Suha neighborhood of Jung District, it lost its old charm.

If you walk past Cheongjinok toward the Jongno District Office, you’ll come upon the Jongno Promotion Center. Although the center is advertised as a place where you can experience the history and culture of Jongno, few people pay much attention to it.

True, the Jongno Promotion Center has the trappings of buildings of the past: the low fence, the platform for holding jars of sauce, the cornerstone, and the tile roof. But it fails to capture the personality of Jongno because it doesn’t fit in with its surroundings.

I detect a whiff of a knock-off Hollywood film set here that really bothers me. The stench is even worse at the Donuimun Museum Village, across from the Kyunghyang Shinmun building.

It would be foolish to expect the muses to inhabit a stuffy memorial.

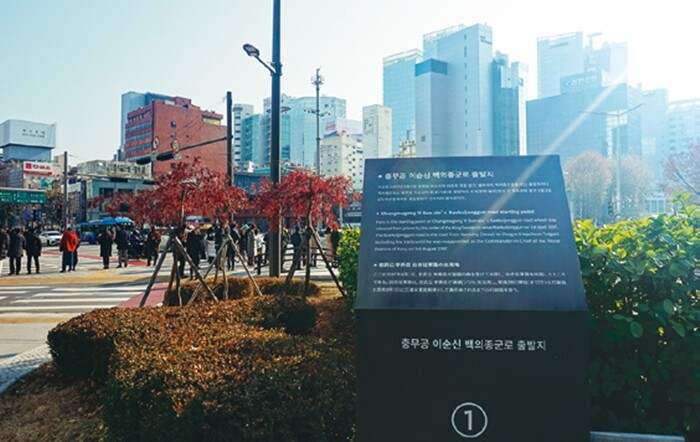

Returning to the main street at Jongno, I stand at the intersection by Jonggak Station. a plaque outside Exit 1 tells me that this is where Yi Sun-sin, the famous admiral, set out, without any title or authority, to save his country from an invading Japanese army on Apr. 1, 1597. That was the day Yi was released from a prison at the Bureau of Crime, located here during the Joseon Dynasty.

Across the street is Jongno Tower, a landmark of Jongno that was built on the site of the Hwasin Department Store, Korea’s first department store. The top of the building is propped up on three pillars, with a gap in the middle like a donut hole. Top Cloud, the restaurant on the 33rd floor, is renowned as a date spot; it offers a splendid view of the city at night.

Across the main Jongno thoroughfare is Bosingak Belfry. The site is best-known as the location of a bell-ringing ceremony held on New Year’s Eve. But what Bosingak reminds me of is the lyrics of “Song of a Night in Seoul,” a popular number performed by Hyeonin and Jeonyeong.

“Roaming through the alleys behind Bosingak / I sighed over that torn-up letter /At an intersection where the horse chestnut leaves rustle, I threw away a cigarette / But its embers didn’t cool as my feelings and your feelings did.”

Today, the streets of Jongno are dominated by sighs and terrors. But before long, the tolling of the bell will tell us that the crisis is over. After all, Jongno is where Yi Sun-sin, down on his luck and with nothing more to lose, got back on his feet.

By Son Kwan-seung, travel writer

Edited by Seoul&

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 2AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 3[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6The dream K-drama boyfriend stealing hearts and screens in Japan

- 7Korea protests Japanese PM’s offering at war-linked Yasukuni Shrine

- 8“Korea is so screwed!”: The statistic making foreign scholars’ heads spin

- 9‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 10Korea sees more deaths than births for 52nd consecutive month in February