hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Seoul travels] Remembering greatest storyteller of Joseon Dynasty on Supyo Bridge over Chunggye Stream

I've befriended two forms of liquid as the social distancing regime has dragged out into the long term and I’ve spent more time telecommuting.

One is “black liquid,” namely the coffee I drink from early in the morning until around midday, and the other is “red liquid,” or the wine I enjoy in the evening. It’s tough to imagine how I might weather this dark and difficult tunnel without these two friends of mine.

I find myself thinking of the Joseon-era scholar who was the first to imbibe wine overseas. He was also the first of the “side street travelers”: Lee Gi-ji, who traveled China back in the early 18th century when it was ruled by the Kangxi Emperor.

In 1720, the 30-year-old Lee visited Qing-era China with his father, who was in charge of a delegation of envoys. He visited a Catholic cathedral in Beijing seven times, tasting the wine there and experiencing pastries such as sponge cake and egg tarts.

In return, he offered the Western priests steamed rice cakes (sirutteok). In these ways, he was a traveler who made quite a distinct impression indeed. A record from Oct. 10, 1720, in his “Iram’s Record of Travel to Beijing” — titled after his own pen name “Iram” — explains:

“I was given a glass of Western wine. The color was deep red, and the taste was quite rich and refreshing. I’ve never been able to drink, but after drinking a full glass I did not feel intoxicated. Instead, there was a slightly warm feeling that rose as my stomach settled.

It is Korea’s first recorded example of wine-tasting. The “Jehol Diary” by Bak Ji-won — known by his pen name “Yeonam” — is more famous to Koreans. Yet Lee had visited Beijing 60 years ahead of Bak and had a momentous influence on later intellectuals of the Northern School (Bukhak-pa).

In “Jehol Dairy,” Bak quotes the words of Hong Dae-yong as he writes, “Our country’s elders such as ‘Nogajae’ Kim Chang-eop or ‘Iram’ Lee Gi-ji all had superlative palates that their successors cannot hope to emulate. Those palates are especially apparent in their excellent observations of China.”

In contrast with other overseas travelers of the Joseon era, Lee sought to view the places others had not been able to. Despite the rigid controls of the Qing’s armored forces, he traveled about the narrow streets (hutong) of Beijing.

“Iram’s Record of Travel to Beijing” is filled with quaint stories of side streets, which is why I refer to Lee as Joseon’s first “side street traveler.”

To Bak and his friends, Lee was a role model who sowed the seeds of reform. Joseon was a very stifling climate for those who were curious and passionate. Bak would later describe the feelings he shared with the Chinese nobility while in Jehol (a former Chinese province also known as “Rehe”):

“My older colleagues at home cannot escape a small patch of the sea, from the time they are born until they age, sicken and die. They have lived like fluttering firefly flickers and mushrooms wilting away in one place.”

The analogies to “firefly flickers” and “wilting mushrooms” echo with a plaintive tone. In 1772, Bak sent his wife and children to his in-laws’ home and set up a residence in the vicinity of the Directorate of Medicine (Jeonuigam). Today, this corresponds to the neighborhood between Jonggak Station and Jogye Temple in central Seoul.

Others who lived close to him included Yi Deok-mu, Yi Seo-gu, Seo Sang-su, Yu Deuk-gong, and Yu Eon. When Bak Je-ga moved there as well, they naturally came together as a group. They were also visited over by Hong Dae-yong and Jeong Cheol-ju, who lived in the area below Namsan Mountain.

The collection of friends who associated at the time is referred to as the White Tower Group (Baektap-pa). The “white tower” in its name — taken from the collection “Baektap Cheongyeon Jip,” for which Bak Je-ga wrote the introduction — was a reference to the three-tiered stone pagoda at Wongak Temple, now the site of Seoul’s Tapgol Park.

The members would often leave their homes to meet over drinks on the side streets around Jongno and Cheonggye Stream. Fittingly for someone who enjoyed drinking, Bak Ji-won wrote one piece titled “Chwidap Unjonggyogi” — literally meaning “a record of walking on Unjong Bridge while drunk.”

His description of reaching Supyo Bridge on Cheonggye Stream is a particular highlight:

“I heard the cries of digging frogs, sounding like refugees gathered for a legal dispute before a lord who is blind and hard of hearing. The chirping of cicadas was like reciting of texts near examination day to commit them to memory in a village school that adheres to a strict daily routine. The chicken’s call was like a lone scholar who regarded it as his mission to speak the truth.”

This was the world seen by Bak, who considered himself an “outsider scholar” throughout his life despite his great abilities.

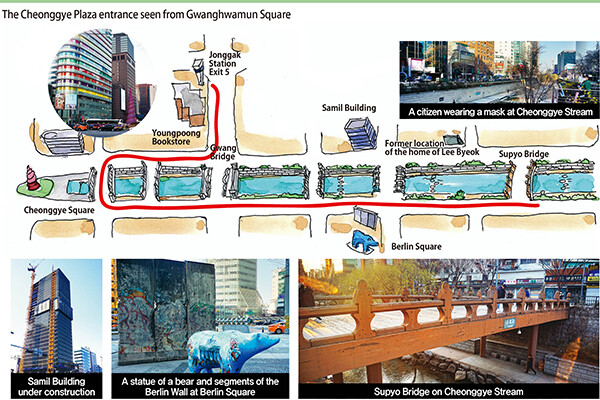

The path described in this piece begins around Jogye Temple and goes past Jonggak Belfry to Gwangtong Bridge and Supyo Bridge on the Cheonggye Stream. Supyo Bridge was built in 1441, in the 23rd year of the reign of King Sejong, with the goal of measuring the stream’s water level. It was also the main bridge by which the monarchs of Joseon crossed the stream.

While King Sukjong was crossing the bridge one day, he saw a beautiful woman nearby and brought her to the palace. That was none other than the famous Jang Hui-bin, who later became the royal consort and mother of the crown prince. That’s one of the romantic stories associated with the bridge.

When the Cheonggye Stream was being paved over in 1958, Supyo Bridge was dismantled and later moved to Jangchungdan Park. When the Cheonggye Stream was restored, it was no longer wide enough to accommodate Supyo Bridge, so a wooden bridge was built instead of the original stone bridge.

A sign next to the bridge says that this was the location of the home of Lee Byeok, Korea’s first adherent to Catholicism. But sadly, I couldn’t find any mention of Bak Ji-won, the greatest storyteller of the Joseon Dynasty, or his friends.

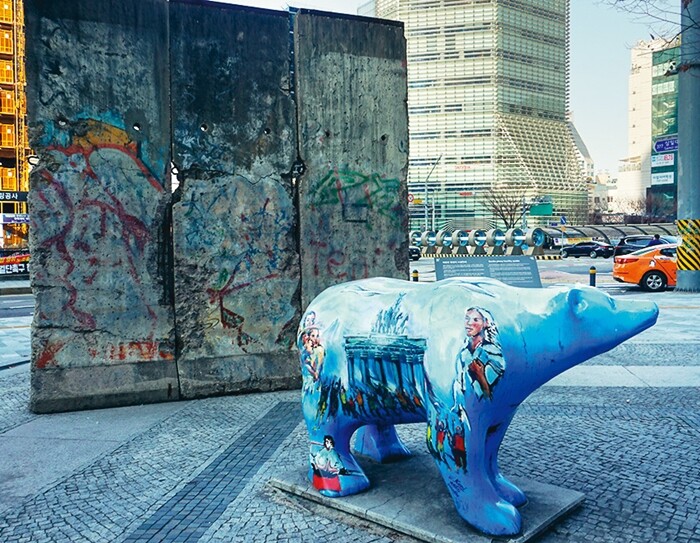

Today’s Supyo Bridge stands next to Samil Bridge. On one side of that bridge is the Samil Building and on the other side is Berlin Square, which contains a section of the Berlin Wall and a statue of a bear, the symbol of Berlin.

The area west of Supyo Bridge, in the direction of Cheonggye Plaza, has been redeveloped, and skyscrapers stand there today. But to the east of the bridge, there are clusters of small run-down machine shops. That’s also the site of the Jeon Tae-il Museum.

The pandemic has put small business owners in the area in danger of going out of business, and they can often be seen anxiously smoking a cigarette. Back in the days of the original Supyo Bridge, Bak Ji-won himself was also short of funds, as well as hope.

Privation makes us look at the world from a different perspective. Privation gives rise to desperation, which in turn empowers us to transgress taboos.

Hong Dae-yong, Yu Yeon, Lee Deok-mu and Bak Je-ga had all been to China before. Their trips were an inspiration for Bak Ji-won, and his own chance finally came in 1780. After crossing the Great Wall of China, Bak at last reconciled himself with his age.

As a leader of the Northern School, he kindled a great passion for social reform in a movement known as Silhak, which means “practical learning.” Privation had been the dynamo that produced a new energy.

The pandemic is an extremely painful time, but it also offers a chance for innovation.

The Cheonggye Stream and the surrounding alleys are where Park developed a unique approach to finding new insights in the teachings of the past.

That same approach should be applied in our own era by governments, companies and individuals.

By Son Kwan-seung, travel writer

Edited by Seoul&

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 3[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 4[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 5No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 6Marriages nosedived 40% over last 10 years in Korea, a factor in low birth rate

- 7Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 81 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows

- 9[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 10Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?