hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Life finds a way in Arctic, where alien-like sponges feed on fossils

The deep-sea regions of the Arctic are one of the most inhospitable environments for life.

In addition to the frigid temperatures, the area is covered in thick ice throughout the year, which blocks nearly all the sunlight needed for photosynthesis. The distance from land also means that there are no nutrients filtering in.

Yet within this environment, a unique ecosystem has been discovered — one dominated by giant sponges.

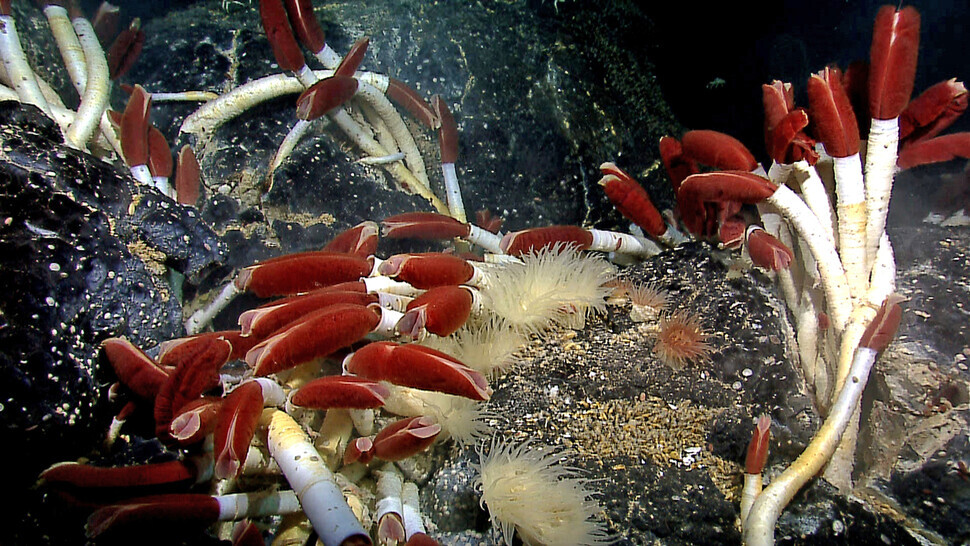

With an average age of 300 years and diameters of up to 1 meter, the sponges were found, surprisingly enough, to be feeding on fossil remnants from tubeworms that survived on volcanoes active thousands of years ago.

An international research team on the Polarstern, an icebreaker affiliated with Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, conducted a survey on the Langseth Ridge, a deep-sea mountain range in the Arctic Ocean to the northwest of Greenland. In the latest issue of the scientific journal Nature Communications, they report discovering a large sponge habitat spanning a 15-square kilometer area around seamounts.

In a press release from the institute, the article’s corresponding author Antje Boetius said, “Thriving on top of extinct volcanic seamounts of the Langseth Ridge we found massive sponge gardens, but did not know what they were feeding on.”

Previously, the seamount was home to a diverse range of life, including tubeworms and shellfish, thanks to the warm, sulfur-rich water emitted from hydrothermal vents. But 2,000 years ago, that activity stopped.

The sponges were found to grow as big as 1 meter in diameter and 25 kilograms in weight and functioned as the dominant species in the seamount ecosystem. The sponge’s main habitat was the peak of the seamounts, at depths of 500-700 meters.

An analysis of the collected sponges showed that a symbiotic relationship with microorganisms is what enabled them to thrive in such an extreme environment.

“The microbes have the genes to digest refractory particulate and dissolved organic matter and use it as a carbon and nitrogen source,” said Ute Hentschel, a microbiologist from the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research who was on the research team. Hentschel explained that those are the energy sources the sponges need to survive.

The sponges and microbes feed on the fossilized tubeworms around hydrothermal vents that were blocked up thousands of years ago.

“Our analysis revealed that the sponges have microbial symbionts that are able to use old organic matter [. . .] to feed on [. . .] the tubes of worms composed of protein and chitin and other trapped detritus,” said first author Teresa Morganti, a sponge expert at the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology in Bremen, Germany.

This is the first time that scientists have discovered animals that can eat fossils. Another notable fact is that this dietary habit was made possible through symbiosis with microorganisms.

The researchers said the sponges function as “ecosystem engineers” on the seamount. The sponges weave silica-based spicules into a mat that provides a living space for other organisms and also catches particles that they can eat.

The research explained that the sponges help form a hot spot that is “rich in species, including soft corals,” despite the extremely nutrient-poor environment.

But how long can this sponge garden be maintained in the Arctic Ocean? The researchers predicted that the sponges could continue absorbing the tubeworm detritus for at least several thousand more years because the cold temperature of the water slows their metabolism.

A more immediate threat is climate change.

“With sea-ice cover rapidly declining and the ocean environment changing, [research] is essential for protecting and managing the unique diversity of these Arctic seas,” Boetius said.

This finding shows how much we still don’t know about our planet’s life-forms, and in particular ecosystems under the ice.

“There is so much alien-like life and especially in the ice-covered seas where we barely have the technology to access, to look around and to make a map,” she said in an interview with the BBC.

One of the first multicellular organisms to evolve, there are more than 8,000 species of sponges distributed across the world’s oceans. They have a remarkable knack for adaptation that was fine-tuned by numerous brushes with extinction. They are thus equipped to endure low-oxygen environments, as well as ocean acidification and warming.

The article “Giant sponge grounds of Central Arctic seamounts are associated with extinct seep life” was published in the journal Nature Communications; DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-28129-7.

By Cho Hong-sup, environment correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/9417144634983596.jpg) [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis![[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track? [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/1617144616798244.jpg) [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

Most viewed articles

- 1Under conservative chief, Korea’s TRC brands teenage wartime massacre victims as traitors

- 2[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- 3Dermatology, plastic surgery drove record medical tourism to Korea in 2023

- 4Value of Korean won down 7.3% in 2024, a steeper plunge than during 2008 crisis

- 5Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 6Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 7[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- 8Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 9First meeting between Yoon, Lee in 2 years ends without compromise or agreement

- 10Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors