hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

His adoption papers said he was an orphan, but he remembers his childhood home in Korea clearly

Editor’s Note: To mark the 35th anniversary of the newspaper’s founding, the Hankyoreh is featuring the stories of 20 transnational Korean adoptees in several installments. May 11 was Adoption Day, and this year marks 70 years of international adoption from Korea.

South Korea is also the third country in the world, after Chile and Ireland, to launch a state-level investigation into human rights violations in the adoption process.

The Danish Korean Rights Group (DKRG) is the world’s largest community of Korean adoptees, with more than 650 members from 10 countries, including Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, and the US.

Since August 2022, the group has submitted 334 adoption cases to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea for investigation, leading to the opening of the investigation into human rights violations in the overseas adoption process in December 2022.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission plans to conduct a local investigation in Copenhagen starting in June. The attention of the estimated 200,000 Koreans who were adopted across the world is on the case.

The Hankyoreh respects the desire of international adoptees to restore truth and justice by looking into their history, which has been tampered with from their birth by instances of infant trafficking and record falsification.

These brief personal histories of 20 adoptees are accompanied by their hopes for the TRC investigation — that the truth is revealed, and they can reconcile with their past.

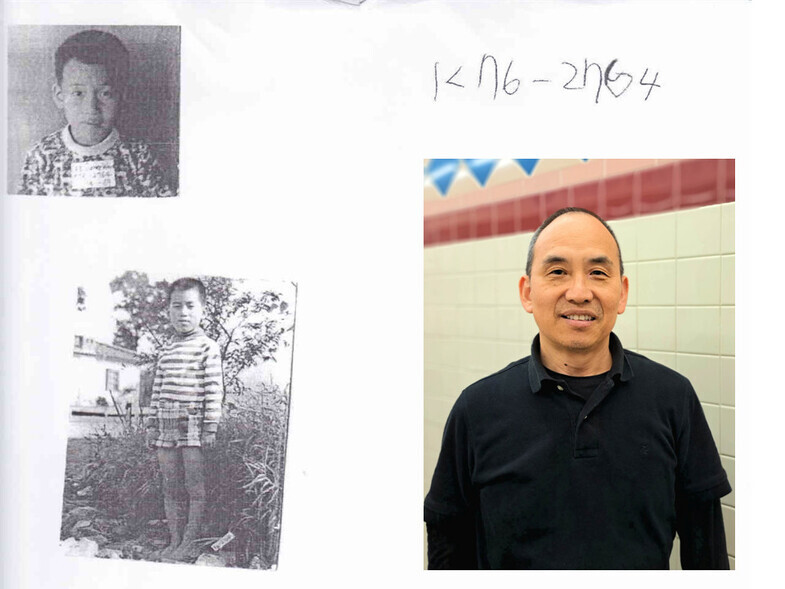

William Vorhees. Adopted at 7 years old. Currently 54 (estimated). USA.“I relinquish all rights to said child.”

On Sept. 22, 1976, the overseas adoption of a “Lee Jung-won” (then 7 years old), was decided by Kim Bong-hee, director of the Sungshil Children’s Home in Daedeok District, Daejeon.

Lee’s birthplace was marked as unknown, and there were no records of his parents, meaning that Lee was an unregistered child, an orphan with no connections.

Because he was an orphan, he could be adopted only with the consent of the director of the institution where he lived, according to the Act on Special Cases Concerning Orphan Adoption (enacted in 1961). All that he had to prove his identity was the name “Lee Jung-won” on his adoption papers, his date of birth (Jan. 14, 1969), and the administrative number assigned to him: K76-2764.

Dec. 13, 1976, marked the day that Lee was adopted by an unmarried man with the surname “Vorhees” in California. The adoption was conducted with the approval of Holt Children’s Services, which functioned as Lee’s guardian.

Upon arrival in the US, Lee was given the name William Vorhees. This is how Vorhees was reborn, one of the many people who were adopted overseas under the Act on Special Cases Concerning Orphan Adoption.

But when Vorhees first saw his adoption papers in 2017, he had questions. For one thing, there was no record of his adoptive mother on his adoption papers. All that remained was a partially crossed-out address. According to the Act on Special Cases Concerning Orphan Adoption of 1976, Article 3 stipulates “parents” — that is, mother and father — as a requirement for adopting.

However, he was adopted into a single-parent family with no adoptive mother. Based on this, Vorhees believed that his adoption process was not legal, and through the Danish Korean Rights Group (DKRG), he applied to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in August 2022, asking for an investigation to determine whether he suffered human rights violations during the adoption process.

The Hankyoreh collected letters from those who applied to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to bring the issue of overseas adoption back to the forefront. Among them, we interviewed Vorhees, who could give a specific testimony based on his memories.

“The illegal nature of my adoption is obvious,” he said via videoconference on May 6.

He is the first letter-sender we interviewed. He suspects that the name “Lee Jung-won” and date of birth given to him were also falsified.

There is one part on Vorhees’ adoption papers that has a sentence that could be used to identify his connections. “

“The mother was raising the child as a seamstress, but after she ran away from home, the child came into care.” Who wrote that line and when is currently unknown.

“The adoption papers said [my birth mother] was single, but I have clear memories of my father and mother,” Vorhees said, “so I think [the papers] were falsified.”

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission raised the issue of illegal adoption by releasing a letter from the Korea Social Service, in October 2022, showing that it had “falsely filled out the birth records and the survival of the birth parents.”

Vorhees states that he was kidnapped and brought to the home. He says he was visiting a market in the city with his mother so that she could sell produce. He remembers his mother was wearing a long dress and rubber shoes with pointed toes.

“Out of nowhere, a man dragged me away. I cried so hard, but that didn’t help anything,” he said. “The next thing I knew, I was at the Sungshil Home.” He was then taken to Holt Children’s Services, where the adoption process began.

“He’s a bright child who understands everything adults say to him and is very good at singing nursery rhymes and popular songs. He doesn’t take many naps and isn’t a very picky eater. He listens well to adults and gets along with strangers. He is of average height and weight. He is expected to grow up to be a normal child.” (An excerpt from Vorhees’ adoption paperwork)

His adoptive father never confirmed the truth of his adoption to him either.

“He never told me why I didn’t have an adoptive mother, or how it was possible for me to be adopted without an adoptive mother.”

“My mother and father were hard-working farmers,” Vorhees said, describing his life as Jung-won. “Our house had a thatched roof with mud walls and a hanji door,” he says. “The kitchen was on the left [relative to the front door], with a traditional wood-burning stove and three large water barrels containing grain. Behind the house, there were three kimchi pots buried in the ground.”

What was absent from his adoption papers was clearly present in his memories.

Vorhees describes his biological father as “short but intense.” He also remembers his father sitting next to a pile of straw in front of the house, quickly twisting rope. “I remember playing on the ground and watching in wonder at how fast his hands moved.”

In 2017, he saw his adoption papers for the first time. The truth had been kept in a drawer for years, uncovered.

“All my life, I felt worthless because I didn’t know who I was or where I came from,” Vorhees said. “I even thought about ending my life. I didn’t even read my adoption papers because I was afraid.”

It was only recently that he realized that his memories conflicted with the documentation.

“My memories of Korea as a 7-year-old have stayed with me all my life,” he remarked. “As a parent of children who are now adults, if one of them had been kidnapped, I would have spent my life searching for them.”

“I am not seeking any form of retribution or recompense,” he said. “I just want to know if there is someone out there who misses me as much as I miss them.”

By Kwak Jin-san, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?![[Column] Life on our Trisolaris [Column] Life on our Trisolaris](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0505/4817148682278544.jpg) [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

[Column] Life on our Trisolaris- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

Most viewed articles

- 160% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 2[Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- 3Amid US-China clash, Korea must remember its failures in the 19th century, advises scholar

- 4New sex-ed guidelines forbid teaching about homosexuality

- 5[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- 6How daycares became the most viable business for the self-employed

- 7Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 8OECD upgrades Korea’s growth forecast from 2.2% to 2.6%

- 9Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 10[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art