hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

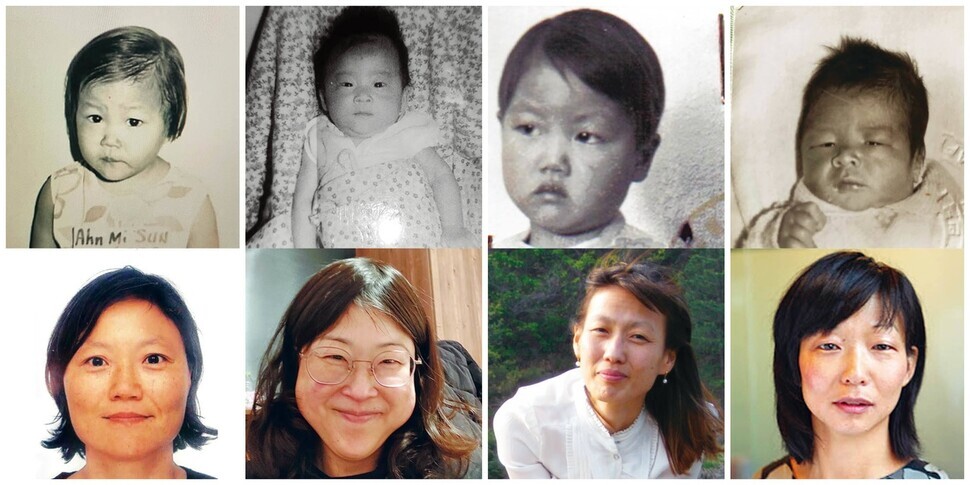

Transnational Korean adoptees seek truth that was kept from them throughout their lives

Editor’s Note: To mark the 35th anniversary of the newspaper’s founding, the Hankyoreh is featuring the stories of 20 transnational Korean adoptees in several installments. May 11 was Adoption Day, and this year marks 70 years of international adoption from Korea.

South Korea is also the third country in the world, after Chile and Ireland, to launch a state-level investigation into human rights violations in the adoption process.

The Danish Korean Rights Group (DKRG) is the world’s largest community of Korean adoptees, with more than 650 members from 10 countries, including Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, and the US.

Since August 2022, the group has submitted 334 adoption cases to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea for investigation, leading to the opening of the investigation into human rights violations in the overseas adoption process in December 2022.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission plans to conduct a local investigation in Copenhagen starting in June. The attention of the estimated 200,000 Koreans who were adopted across the world is on the case.

The Hankyoreh respects the desire of international adoptees to restore truth and justice by looking into their history, which has been tampered with from their birth by instances of infant trafficking and record falsification.

These brief personal histories of 20 adoptees are accompanied by their hopes for the TRC investigation — that the truth is revealed, and they can reconcile with their past.

Kim Mi Ae. Adopted at 2 years old. Currently 52 years old. Netherlands.

The moment my mum decided to leave my dad and my siblings behind and returned to her hometown in the southern part of Korea, she turned my life upside down. She took me with her since I was still so young. She left me at my grandparents’ home where my youngest aunt took care of me. After approximately seven months, my grandparents told my mum to take me with her and leave. Her boss in the big city of Gwangju told her she could not work and pursue child-rearing at the same time, and suggested handing me over to a rich family who wanted to raise me as their daughter. So did my mum, according to her narrative. That was the start of my second personality.

I became Kim Yung Hee, the little girl who was disconnected from her origin. I ended up in a babies’ home in Gwangju where I was selected for international adoption. After a year in the orphanages in Gwangju and Seoul, I ended up in the Netherlands. My past had been washed away and I was ready to start a whole new life as Alice, a Dutch girl with an Asian appearance.

Though I was not able to remember anything anymore from my early years, I vividly remember my tears, my sorrow and pain from my youth. I often tried to comfort myself with the image of my mother looking up at the stars, wishing me all the love in the world. I did my best to become a strong and independent girl she could be proud of and learned to hide the tears and sadness of the Korean little girl I once was.

After a troublesome search for my family, I finally found them in 2008. I even moved to Korea for a second time with my husband and children. We could not relive the lost past but we could make new memories together. As adoptees with a strong connection to Korea, there was a feeling that we belonged there. But also having a life with friends and family in the Netherlands, we felt the heavy weight of international adoption throughout our lives. In particular, the burden of being forced to make a mandatory choice between our two countries, two personalities, and two identities provokes a feeling of shortcomings toward the one we sadly have to leave behind.

Our quest of finding the truth behind our adoptions, to understand the adoption system and find out who was responsible for the misdeeds in our adoptions is the driving force behind my decision to establish the Netherlands Korean Rights Group (NLKRG) in the Netherlands. Hand in hand with the sister organizations united in the Overseas Korean Rights Group (OKRG), we hope to discover the truth and to be reconciled with our past and motherland. Only after accomplishing that, we adoptees can start our own healing process after a long journey of insecurity and loss of who we are.

The TRC investigation will not erase the heavy burden of disconnection from our original identity, the tears and pain, but I sincerely wish the outcome will give justice by revealing the whole truth behind the wickedness of this adoption system. And I hope it will ease my heart that those misdeeds toward Korean children will be banned forever from happening again.

Spent life thinking I was orphaned only to see my biological parents’ names on the papers

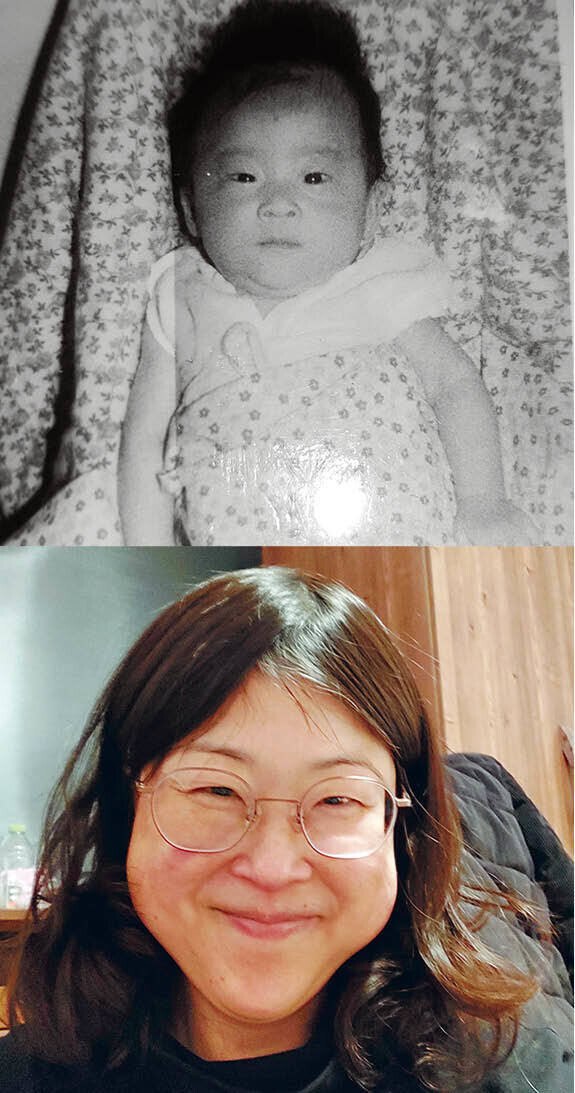

Maria Svendsen. Adopted at 4 months old. Currently 45 years old. Denmark.

I was an orphan. Found in a basket on the doorstep of a children\'s home with a paper slip in my clothes. For 45 years this was my adoption story and my only link to Korea.

I was only 4 months old when I was sent to Denmark, a tiny country in Scandinavia, the land of the Vikings. My family and friends are blonde with blue eyes.

I grew up with loving and caring parents in a typical middle-class home. A home in a big house with homemade lunch boxes, a dog, my own pony and a room full of toys.

Last year I heard about the Truth Commission, and I started to search for information about my adoption story.

Now I know that I am not an orphan. I know that the story about the paper slip in my clothes is a common history in many of the adoption papers from Korean adoption organizations.

The Korean adoptions bureau tells me that they have the names of my biological parents. That they were married, and I have siblings.

For me, this is mind-blowing new information. I am not an orphan? Do I have siblings? Do I look like them? Are they still alive?

My new adoption story ends with more questions than answers, and therefore I have a lot of hope for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. I hope that the work will bring information about the overseas export of children.

I hope that the work of the commission will be supportive, and that the Korean community will show recognition and support for women and families who gave away or lost children for adoption.

I also wish that all shall have a right to know our history.

The photo in my file may not even be me

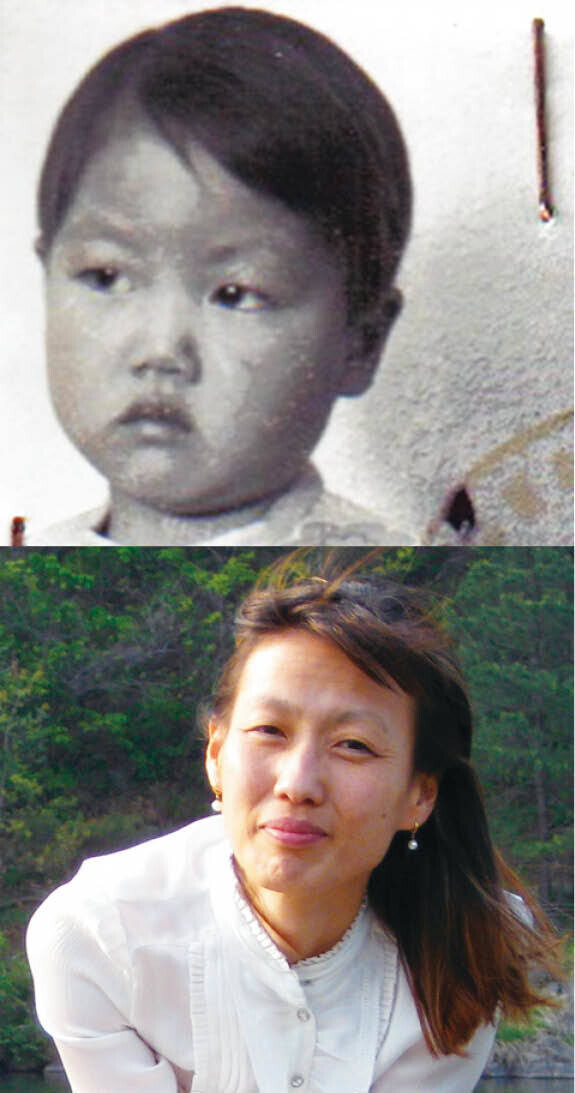

Marie. Adopted at 3 months old. Currently 46 years old. Netherlands.

How can one describe the truth? There is your truth, my truth and a judge often rules within those parameters of truths, generally considered as the truth. Can something be considered true when one has not seen it, or when witnesses are long gone? Will the truth set one free, as stated in the Bible, even if it stems from trauma?

Often, experience teaches that one can only answer those questions after being given the known facts, and, just as important, the unknown facts. By doing so, one can start combining facts and eventually reconstructing their truth. To get there, one needs honesty, resilience and sometimes even luck.

In my own adoption case, I have been resilient, and I will be resilient till the end of days. However, my story lacked luck and honesty, or facts were missing.

I was born sometime in May 1976, probably in Ulsan or Busan, but from there, the unknown is becoming front and center. I suspect I traveled to the Netherlands on the papers of a baby that had passed away. Nobody ever told me, my file at KSS does not mention anything peculiar about my case. However, the baby in the picture in my adoptive file is very likely not me, or at least does not look like me. Korean parents are not mentioned in my file, and until this day, I have not been able to find them.

So, my truth became that I was born on May 19, 1976. I might have been abandoned, or nothing of my biological background is known. My Korean name, Yoo Won Hee, is likely given by the orphanage, probably NamKwang Orphanage where I briefly was. But, as stated before, my papers are sketchy at best, the one thing I can state as a fact is that I spent time at KSS, Korean Social Services Orphanage in Seoul. Although I lived about the first four to five months of my life in Korea, most facts are unknown, and most likely will stay that way.

I find my truth in unknown facts. Parents unknown, date and place of birth unknown. Possible genetic diseases might be known someday, but not for now. The only fact I know for sure is that it took hard work to come to terms with these truths about my life. Will it ever set me free? The jury is still out on that one fact.

Still unable to fully view documents

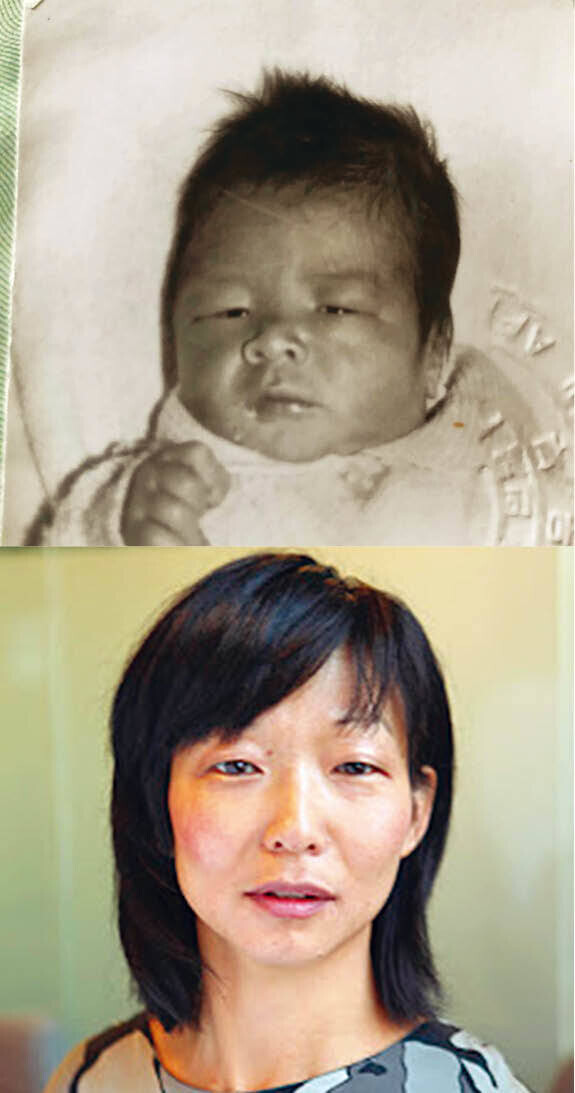

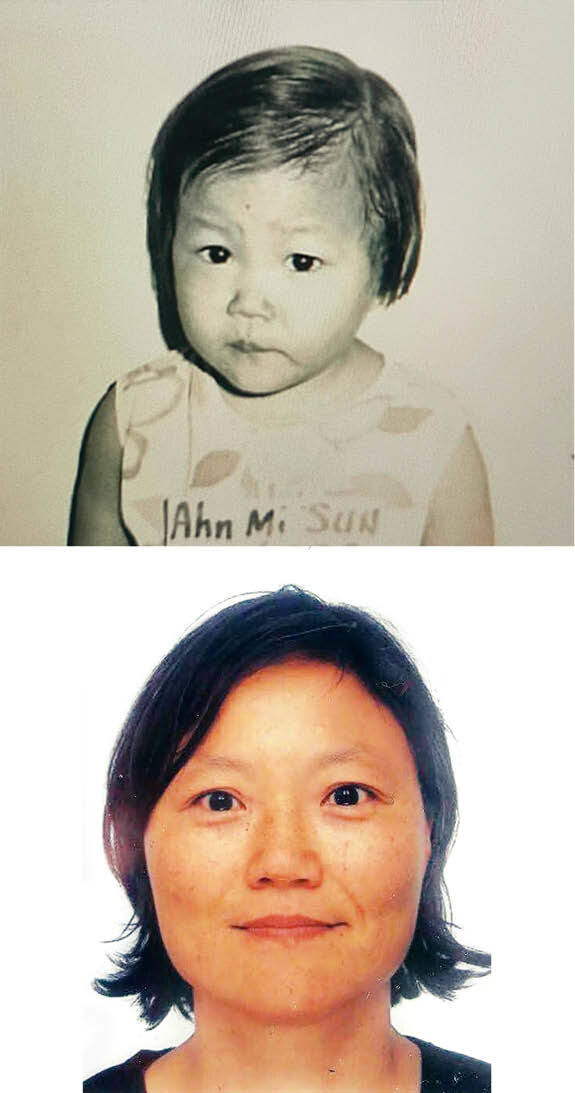

Ahn Andersen. Adopted at 2 years old. Currently 54 years old. Denmark.

When I first heard of the TRC case, I knew that I had to support it for several reasons.

First of all, it was a great possibility for me, personally, to have my voice heard. This was important for me as I have been struggling since 2004 to get the chance to see all the documents in my adoption file.

At my first encounter and first visit to the Holt office back in 2004, I saw that there were several documents in my file to which I had no access. Asking the Holt social worker what papers these were, I got the reply that they were “confidential papers.” It required the adoptive parents’ agreement if I wanted to see those papers. Going back to Holt’s office the following year, in 2005, with a consent form from my adoptive father in my hand I was told: “Well, now ‘the law’ has changed, meaning that your consent from your adoptive father doesn’t allow access to those papers.”

So, bam! Just like that had Holt changed “the law.” I don’t know which law the social worker referred to or if it was even true what she said. The bottom line is I didn’t get access to the hidden papers. And now, as of 2023, I still haven’t seen my complete adoption file.

Secondly, I think that this is a huge and historic opportunity for adoptees around the world to get a sense of justice in this unjustified and unfair position that we are in! We, the adoptees, are the weaker part in the adoptee triangle often referred to in this exact order: Adoptive parents. Birth parents. And the adoptee!

We, the adoptees, are the only party not being asked in the adoption process. Decisions were made without our consent. I’m well aware that, obviously, grownups have to make decisions on behalf of a child. Responsible grownups. However, in many adoption cases, it turns out that the so-called “grownups” (adoption agencies) were not so responsible. It now comes to light that in some cases adoption agencies have been lying up front to both adoptees and birth parents. We know that now. For decades we thought it was maybe just a presumption and a one-off case. But now we see the whole frame from a meta-perspective. We see the systematic lies and intended forgeries and fraud. We are aware of it now. It has been documented.

Thirdly, because I hope the outcome of the TRC case will result in the right for all adoptees to obtain unconditional access to ALL information in his or her adoption file. I hope that all adoptees who want it will be granted the possibility to finally one day be the owner of the original papers and documents in the adoption file. Why should the adoption agencies possess our documents?

An example: When you graduate, your school or university gives you a certificate. It’s your belonging. The school keeps a copy, but you retain the original document. Why is it not the case in the adoption system? Why do adoptees not get the original documents? Why are we not even allowed to see all the papers? And yet, there is a huge difference between a school/university certificate and an adoption file!

I sincerely hope that the researchers will reveal all that there is to reveal. Turn any stone there is to be turned. Make the light of justice shine on even the most sad, shady and obscure corner of the big money machine called adoption. I hope that greedy and dishonest adoption agencies will all be shut down as soon as possible. Just like we have witnessed recently in France.

Let only the adoption agencies that handle 100% fully legal adoptions. Adoption agencies that operate within the Hague Convention and don’t violate the UN Human Rights of the Child. Adoption agencies that side with the child in order to find the best solution for the child — and not the other way round: finding a child for a childless couple — and therefore seek to sincerely work to find a good family for the child in need. That being a real orphan. Not a paper orphan! Adoption agencies that don’t charge any fees — as money will not be part of the adoption process. Adoption agencies will then no longer be money machines.

I’m grateful that the Commission accepted this case and I hope this is only the beginning of the changing process within the adoption systems worldwide. I’m happy to find Korea taking the leading role in this regard.

It takes an adoptee (and birth parents) to know how big the loss connected to an adoption is. Being an adoptee implies so much loss. A loss that might be difficult to even define as many of us don’t know exactly what we have lost. Some adoptees even lost their lives in the adoption process. May they forever rest in peace!

I submitted my case to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in August 2022 and I am proud of being part of the first batch.

Que justice soit faite. Let justice be done.

By Koh Kyoung-tae, senior staff writer

Joint planning and execution by Han Boon-young, co-founder of the DKRG

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Life on our Trisolaris [Column] Life on our Trisolaris](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0505/4817148682278544.jpg) [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

[Column] Life on our Trisolaris![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

Most viewed articles

- 1New sex-ed guidelines forbid teaching about homosexuality

- 260% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 3Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 4Presidential office warns of veto in response to opposition passing special counsel probe act

- 5[Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- 6S. Korea discusses participation in defense development with AUKUS alliance

- 7OECD upgrades Korea’s growth forecast from 2.2% to 2.6%

- 8Japan says it’s not pressuring Naver to sell Line, but Korean insiders say otherwise

- 9Opposition calling for thorough investigation into Pres. Park’s unelected power broker

- 10Ruling and opposition parties agree to special prosecutor for Pres. Park/Choi Sun-sil scandal